Shaik is a neurology resident.

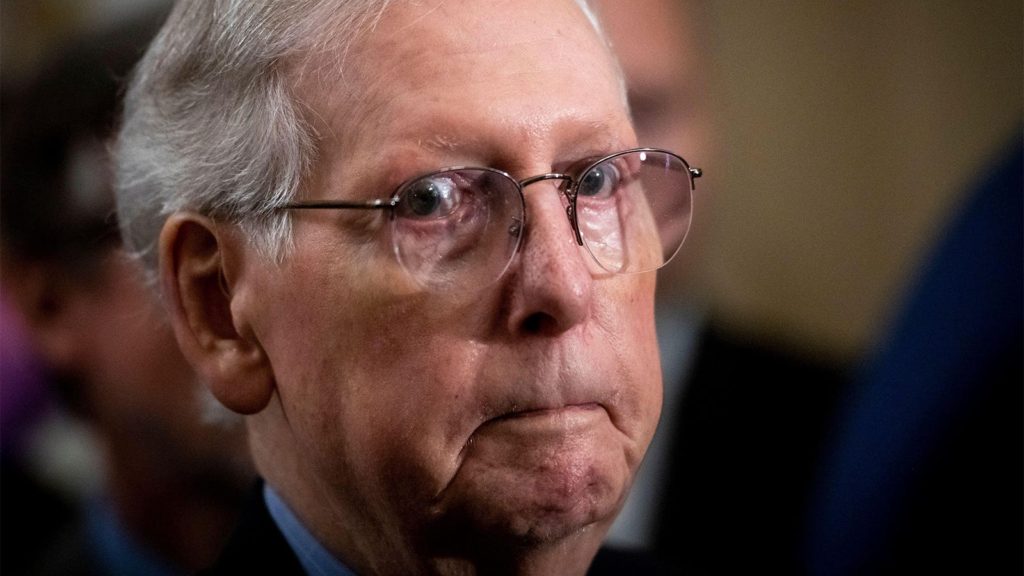

When news broke earlier this year about Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s (R-Ky.) hospitalization for a concussion (a type of traumatic brain injury [TBI]) after a fall, I thought back to the many patient-made paintings that graced the walls of a rehabilitation hospital where I rotated as a medical student. There I saw patients whose lives had quite literally been turned on their heads, whether from a stroke or motor vehicle accident or even “just a fall.” They were mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, children, and very often, grandparents. And often the fall was just the start of their problems, similar to what we have seen in the news more recently with McConnell’s multiple speech arrests, which may suggest an underlying neurological issue.

Per the CDC, someone in the U.S. is hospitalized for a TBI-related problem nearly every 2.5 minutes, and nearly every 8 minutes someone dies from a TBI-related issue.

This problem is particularly notable in those above age 75, as this group has the highest rates of TBI-related hospitalizations and deaths — accounting for nearly one in three such hospitalizations and more than one in four deaths. Falls lead to nearly half of all TBI-related hospitalizations, highlighting how “just a fall” can lead to so much more for some patients.

TBIs have also been associated with poorer long-term outcomes in adults. These include increased risk of developing late-onset epilepsy and strokes — both of which have been suggested by outsiders as the mechanism for McConnell’s events of transient speech arrest (although Capitol physician Brian Monahan, MD, recently stated McConnell showed no evidence of stroke, seizure disorder, or movement disorder). Of particular interest, these studies revealed that the association of TBI with stroke and risk of developing late-onset epilepsy are both especially notable in older adults compared to younger individuals. Furthermore, head injuries in adults may also be associated with an increased risk of dementia, and this association increases with more head injuries. What’s more, a year out from even a mild TBI (such as a concussion), adult patients had worse functional outcomes compared to patients who had non-TBI orthopedic injuries.

Taken together, these findings highlight how a TBI, especially in an older patient, should not be taken lightly. But while TBI could potentially increase the risk of someone developing epilepsy, strokes, or dementia, it is only a single factor against a background of several other predispositions, including manageable conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

Another caveat of the aforementioned findings is that the study tracking functional outcomes did not include patients above age 75. This becomes particularly important considering that this age group has the highest rate of TBI, especially fall-related TBI. Since these patients have unfortunately been excluded from many TBI clinical trials because of their age, treatments from these other trials may not necessarily be relevant to older adults. Thus, there is an urgent need for more studies not only looking at outcomes in older adults with TBI but also for new interventions to improve recovery.

Finally, and very importantly, while functional outcomes were worse a year after mild TBI, functional outcomes did improve with time. This essential point illustrates that while someone who has suffered from a TBI may not be 100% back to their prior baseline, there is hope that they can come very close to it and have a new and highly functional normal. Intensive rehabilitation programs may help to facilitate this.

Thus, it is imperative that any patients with head injuries, even “just a fall,” are evaluated by the appropriate medical professional to ensure a more serious injury is not lurking in the background (this is especially true for older adults). It is important to closely monitor such patients over time, and to intervene early in case they do start showing signs of seizures, transient ischemic attacks and strokes, or dementia.

Of course, prevention is key — we should begin with decreasing the risk of falls in the first place. The CDC has a comprehensive list of recommendations that can help our patients avoid falls. These guidelines include recommendations like exercises to improve balance and strength, home modifications such as bathroom grab bars and walking aids, and addressing clinical concerns such as taking vitamin D after hip fractures and cataract surgeries to improve vision.

There is still much work to be done in the field of TBI, but by having a multidisciplinary and preventative approach, we can hope to reduce TBI and improve outcomes to help our patients maximize recovery.

Noor Shaik, MD, PhD, is a neurology resident in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the University of Pennsylvania Health System or the Perelman School of Medicine.

Acknowledgements: I would like to sincerely thank Andrea Schneider, MD, PhD, for her support and guidance in helping write this piece.

Please enable JavaScript to view the