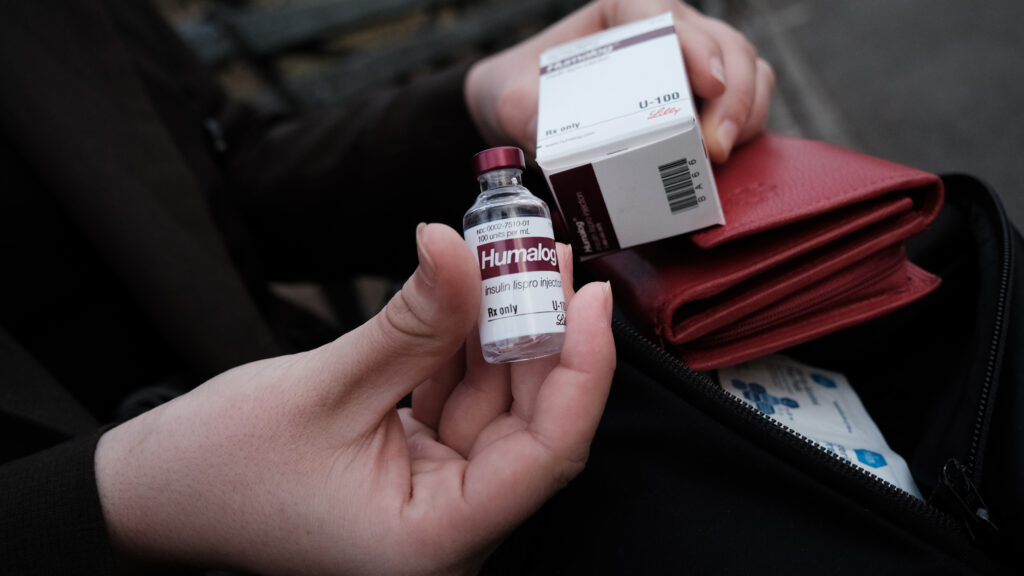

In March, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi — the world’s three largest insulin manufacturers — committed to reducing the U.S. list price of insulin, a drug that millions of people require to live.

Following two decades of sharp increases for consumers, the companies vowed to cut insulin prices for some insulins by at least 70%, meaning many people could see their insulin costs capped at $35 a month in the near future. (Sanofi and NovoNordisk will lower their prices as of January 2024; Lilly reduced it to $35 per month in March 2023.) While pharmacy benefit managers and the rebates paid to them by pharmaceutical companies will continue to drive up costs for patients in the U.S., competition on the horizon could help push down prices.

advertisement

For example, U.S.-based philanthropies, including Helmsley Charitable Trust (where I am a trustee), JDRF, and Peterson Center on Healthcare, have also used grantmaking to help shape the domestic insulin markets by supporting research and development efforts for a new, low price insulin that circumvents the rebate games played by PBMs, health insurance companies, and insulin manufacturers.

These developments will be game changers for Americans who need insulin to live, including people living with type 1 diabetes (T1D). A lack of access to affordable insulin can have grave consequences, including diabetic ketoacidosis, which, when left untreated, can result in seizures, coma, and death. Coupled with major advances in the quality of U.S. care through initiatives like the T1D Exchange and innovative models like Blue Circle Health, the news of a future where that life-sustaining drug is more affordable is certainly something to celebrate.

But while these developments may signal important progress in the U.S., we must not forget about the almost 2 million people living with T1D in low- and middle-income countries who also need insulin to survive.

advertisement

In the lowest-resource settings, treatment and care for chronic illness can be impossible to find. This can mean that being diagnosed with T1D — a disease that can be managed with proper care and treatment — becomes a death sentence. A 10-year-old diagnosed with T1D in a high-income country can expect to live, on average, 50 years more than one living in a low-income country. That disparity is, in part, due to massive barriers to affordable insulin in low- and middle-income countries, including unpredictable access and catastrophic out-of-pocket costs.

Just one example: A person living with T1D in Nigeria can spend more than 20 days’ wages to buy insulin for one month — which, it bears repeating, is a drug that they depend on to survive. In a study of insulin prices across 47 countries, costs ranged up to an entire month’s worth of wages. This means that in some places a person must spend their entire income on life-sustaining medicine.

Now you might be asking, “OK, so what should insulin cost?” It’s a good question. Admittedly, it’s hard to name a number that would be fair to everyone, in every market and health care system around the world. While the largest pharmaceutical and biotechnology sales have an annual average profit margin between 15% and 20%, profits for insulin remain unacceptably high. In studies of countries at all income levels, government procurement prices are estimated to be 2 to 9 times higher than production costs for best-in-class products. We can all agree that no one should have to spend a significant percentage of or all their income just to buy medicine they need to live, while companies rake in profit.

Recognizing the optics, pharmaceutical companies have been working to increase access to insulin through donation programs and other special projects with NGOs and philanthropies. But the fact is those efforts simply don’t meet the demand, leaving one in two people living with diabetes without access to insulin, and causing millions to taking extreme measures to manage the disease. And these goodwill programs are always at risk of being cut in favor of more profitable production lines.

Building a more diverse, sustainable supply of affordable insulin in low- and middle-income countries is both a viable economic option and a moral imperative.

To start, we need more commitment from the private sector to urgently provide equitable access to the best-in-class insulin everywhere. Companies like Sanofi and Eli Lilly are exploring offering new, potentially lower-cost insulin options. However, the patchwork of existing “access” strategies have still left 24 countries without any registered insulins, making access virtually impossible for people in those areas.

Promising innovations — like shared tools to estimate demand — and continued health care delivery research can help assure manufacturers that sufficient demand exists to justify bringing best-in-class products into new markets at price parity with current products. But even beyond product introduction, there is a need for greater transparency around cross-sector price-setting practices, so I commend the World Health Organization and others for supporting nuanced conversations about the true costs of bringing industry-standard insulins to people in low-resource settings.

Second, governments and insulin manufacturers must work together to scale up commercially sustainable access to the newest, high-quality insulin at affordable prices. While high-income countries are using newer, more effective drugs, many low- and middle-income countries only have suboptimal insulins on the market. Though prices are set lower than modern analogues, antiquated products like human insulin are typically slower and less predictable when it comes to controlling blood sugar, forcing users to count carbs and counter crashes over the course of their day — which can be especially challenging in food insecure settings. Older insulins also put people with T1D at a higher risk for dangerously low blood sugar levels while sleeping.

People should not have to rely on decades-old care practices and accept poorer outcomes simply because of where they live. My own daughters live with T1D, and I cannot imagine having to settle for anything less than the best for them. Other families managing T1D deserve the same peace of mind.

Third, to ensure these products can be delivered to patients, countries and donors must prioritize strengthening integrated health care systems for noncommunicable diseases. With growing momentum around strategies like PEN-Plus, a WHO-endorsed strategy that brings T1D care to rural areas by training local health workers to treat the disease in district clinics, there is both the political will and evidence to revolutionize care for conditions like T1D.

And finally, health care workers, civil society organizations, and other patient advocates must be empowered to hold governments and private industry to fierce account, continuing to raise their voices and demand better access to lifesaving care and treatment. The U.S. is seeing firsthand the power of advocacy to lower insulin prices. People who need insulin in low- and middle-income countries deserve the same coalition of advocates, policymakers, businesses, and funders fighting for their access to essential medicines.

The world has promised that everyone living with T1D will have access to affordable insulin by 2030, and right now we’re far from meeting that goal. However, if we can capitalize on this recent momentum and commit to working together as a global community, we can rise to the challenge.

David Panzirer is a trustee of the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.