The descent into dementia can feel like traversing a minefield, coming across new symptoms without the hope of a cure.

But some dementia patients, even up to 10% of people diagnosed with the condition, might actually have undiagnosed liver disease and accompanying neurological problems, a new study in JAMA Open Network suggests. Most importantly, it’s possible their liver-related brain symptoms could be resolved with treatment.

advertisement

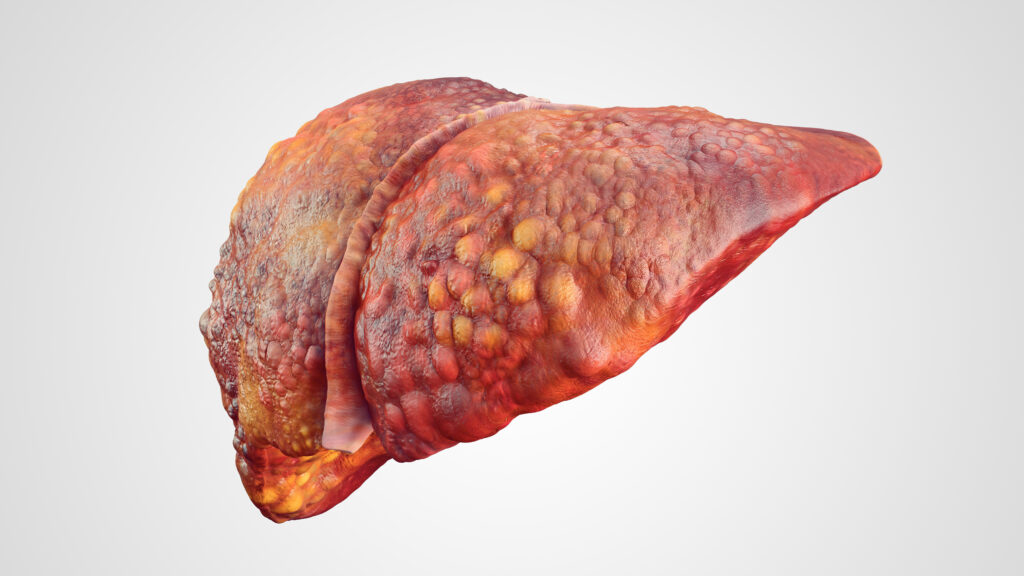

The study, conducted by a group of Veterans Affairs doctors, included 177,000 veterans who had been diagnosed with dementia in at least two clinic visits, and who had never been diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver. Cirrhosis is severe scarring — caused by a variety of diseases and viruses — that inhibits the liver’s ability to perform its many functions.

The first cohort was a group of patients seen by the Veterans Health Administration between 2009 and 2019 (the study did not use 2020 data to avoid the potentially confounding effects of Covid). Using the patients’ lab results and other health records, researchers looked for indications of liver scarring (fibrosis) and calculated the likelihood of cirrhosis using an established formula called the Fibrosis-4 score.

They found that up to 10% of their patient pool had a FIB-4 score high enough — over 2.67 — to indicate potentially serious liver disease. And these patients had never been diagnosed with cirrhosis.

advertisement

But a crucial tie between liver disease and dementia is what occurs in the brains of about 50% of people with cirrhosis: hepatic encephalopathy. When the liver stops removing toxins and waste from the blood, those bits of trash circulate to the brain. There, toxins like ammonia and manganese have a poisonous effect on brain cells. Once encephalopathy moves from covert to overt, patients can experience an array of changes to their cognition, motor skills, sleep and mood — a profile strikingly similar to that seen in dementia, except it’s reversible.

Most of the time, hepatic encephalopathy is treated with either antibiotics to reduce the amount of toxins being produced by certain bacteria during digestion, or lactulose, a synthetic sugar. Lactulose helps drive toxins into the colon and flush them out with smoother bowel movements.

“If a portion of their symptoms is caused by hepatic encephalopathy, which is way easier to treat than dementia, then I think we need to look at that,” said lead author Jasmohan Bajaj, a professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University and provider at Richmond VA Medical Center. (Bajaj has previously received grants from pharmaceutical companies Bausch, Grifols, Sequana and Mallinckrodt. This study was funded by the VA Merit Review.)

Part of the problem is that, for providers, telling apart patients with hepatic encephalopathy and dementia is nearly impossible in a brief appointment, experts told STAT. There’s no quick, simple blood test that can separate one from the other. It takes additional, more labor-intensive tests to figure out if a patient has hepatic encephalopathy. The result might be misdiagnosis.

The study “is describing a phenomenon that we have all seen in our own clinical practice, where people will come to us with a diagnosis of cirrhosis after dementia,” said Elliot Tapper, an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Michigan. (Tapper, who was not part of this study, has consulted for Satellite Bio, Iota, Takeda and Madrigal and previously had a grant from Salix, the maker of the hepatic encephalopathy drug rifaximin.)

Bajaj and his colleagues used two other groups of patients at the Richmond VA Medical Center, including patients seen at the geriatrics clinic last year and who were still alive, to double-check their results from the first analysis. In all, they found high FIB-4 scores in 10.3% of patients, indicating that some might have had hepatic encephalopathy instead of dementia, or in addition to it. They could have relieved the liver-related brain symptoms if only the patients had been checked for liver damage.

Many veterans have risk factors for both cirrhosis and dementia, so the conditions could coexist and feed into each other, Bajaj said. This is particularly true for Hispanic veterans, who are disproportionately affected by dementia, have elevated liver disease risks, and had a higher likelihood of potentially undiagnosed cirrhosis in Bajaj’s results.

Cirrhosis, while a serious and growing concern due to increased rates of metabolic disease and alcohol consumption, is hard to catch. Liver disease often develops silently, over time, and only makes itself known once severe — and irreversible — damage has been done. Primary care providers often don’t think to check for it in their limited time unless patients have some clear risk factor: an alcohol use disorder, or hepatitis B or C infection. Other common disorders, such as high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity, are lesser known as risk factors for cirrhosis.

“It’s not a condition that hurts. Patients don’t come in asking to be screened for cirrhosis,” said Lauren Beste, deputy chief of the general medicine service at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System. “It’s easy to see why it could be overlooked, but it’s just such an important and lifesaving diagnosis to make early.”

The FIB-4 score could be a useful screening tool for providers, even though it’s “far from perfect,” Beste said. The score only requires a basic liver enzyme test, platelet count, and the patient’s age. However, a higher age will skew the formula toward a higher FIB-4 result, which could pick up people without cirrhosis. (In Bajaj’s study, the researchers accounted for that inflation by using the age 65 for patients older than that. The results might be a conservative estimate of cirrhosis rates.)

The FIB-4 score also cannot diagnose cirrhosis — it’s a back-of-the-envelope calculation of someone’s risk. It’s more of a “pointer that you need to look harder and rule cirrhosis out,” said Beste, an associate professor at the University of Washington’s medical school. But given the ramifications of a missed diagnosis, providers owe it to patients to rule out a reversible cause of brain issues, she said.

Bajaj agrees that his study bears out the FIB-4 test as a warning system rather than a diagnostic. “Even if 100% of them had cirrhosis, that does not mean that 100% of them had [encephalopathy]. That just tells you: Be aware. This may be lurking in our patients,” he said.

In other words, the researchers didn’t take patients with dementia, check them for cirrhosis, treat them for hepatic encephalopathy, and document the results. That could be a next step, Tapper said, and a good way of knowing just how many people might benefit from being treated for cirrhosis-related brain symptoms.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.