The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which has been under pressure from scientists both at home and abroad to share more data on the H5N1 bird flu outbreaks in dairy cows, uploaded a large number of genetic sequences of the pathogen late Sunday.

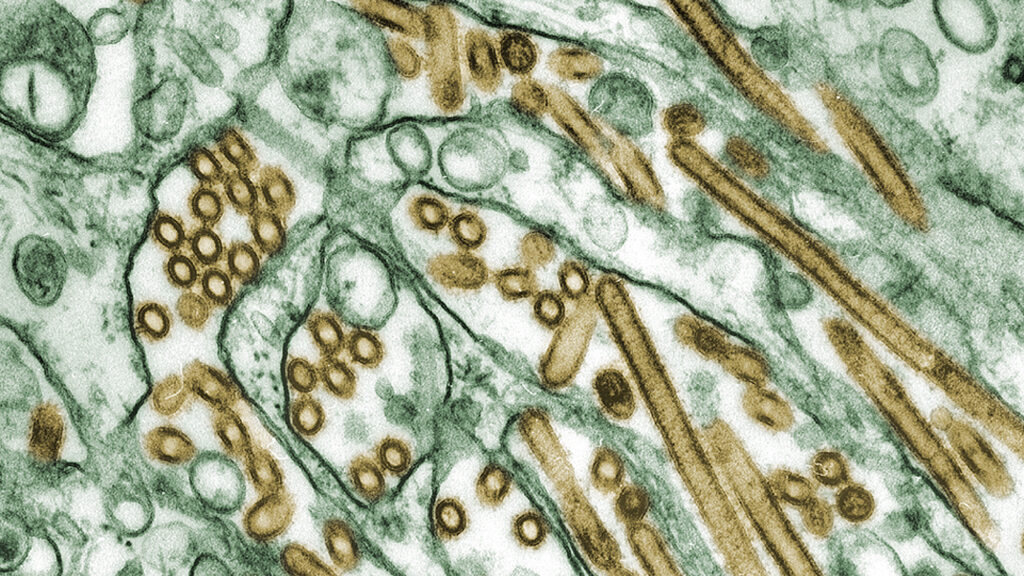

Access to the 239 genetic sequences will help scientists assess whether the dangerous virus has acquired mutations that might make it easier for it to spread to and among mammals, and whether additional changes have been seen as it moves from cow to cow and herd to herd. In addition to virus sequences from cattle, the trove includes sequences of viruses retrieved from cats, chickens, a skunk, a racoon, a grackle, a blackbird, and a goose, the agency said.

advertisement

Rick Bright, a pandemic planning consultant who has been vocally critical of the USDA for being slow to share sequence data, noted the disclosure had “taken a long time.”

“But I’m grateful,” he said of the government’s move. “And eager to see what we can discover.”

“I just hope that data keeps coming,” said Bright, a former director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the former head of the Rockefeller Foundation’s now-defunct Pandemic Prevention Institute.

advertisement

Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona, said that at present what has been posted is raw data, which is highly useful, but will take some time to analyze. “At least now, servers around the world [run by] groups who work on this can start revving up their engines,” he told STAT.

Worobey said it was not quickly evident whether the sequences were from samples collected across various time points in the outbreak, which has been ongoing for weeks.

The USDA announced on March 25 that it had confirmed H5N1 in dairy cows in Texas, a finding that has unsettled scientists who have followed this virus’ progression across the globe and into species after species of mammals. Until now, cows have not been among the animals seen to be infected by the virus.

The department initially shared a number of sequences, all of which appeared to be from the original outbreak in Texas. Since then, 32 herds in eight states have been confirmed to have been infected with H5N1. While it is deadly to poultry and to a number of types of mammals, in cows it does not appear to cause severe illness. But milk production declines in infected cows and the milk produced is thick, off color, and teeming with H5N1 viruses. Farmers have been told to destroy milk from infected cows.

While the USDA believes the virus is spreading from cow to cow, it is as yet uncertain how it is transmitting, noting there doesn’t appear to be large amounts of virus in the nasal passages of infected animals. It has suggested that transmission may be occurring through the milking process, perhaps through the sequential use of milking equipment or the movement of humans among farms.