Americans are facing at least two prescription drug crises simultaneously. One is the outrageously high cost of drugs, which runs to more than $500 billion per year. The other relates to extreme drug shortages requiring rationing of lifesaving medications.

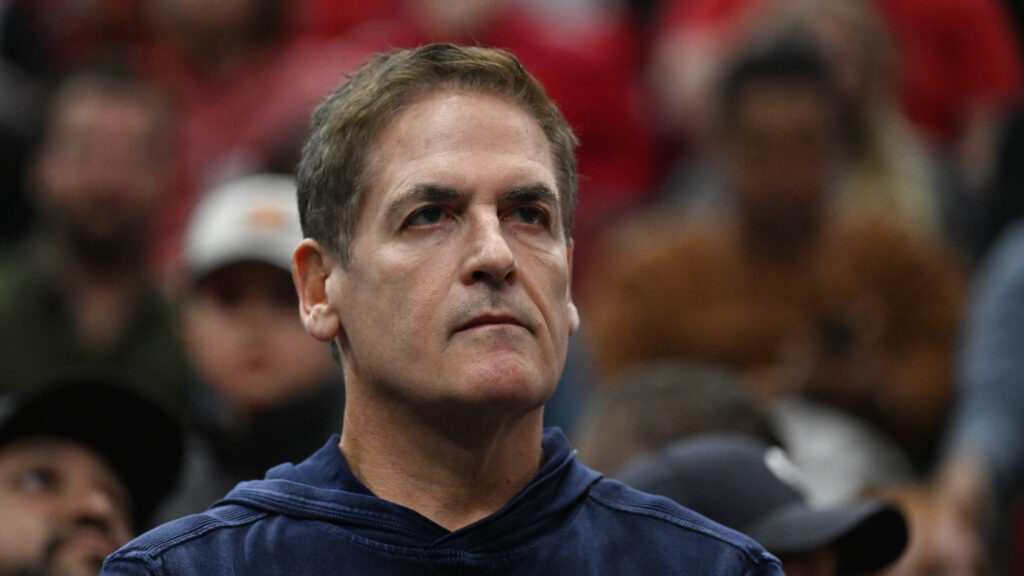

Crises can generate opportunities. Mark Cuban, the wildly successful entrepreneur and NBA owner, has committed himself to solving these two problems. Through the creation of the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC), Cuban aims to reduce drug prices and also drug shortages.

advertisement

He has not done this quietly. The pharmaceutical industry, he proclaims, is “the easiest industry I’ve been in to disrupt.”

Though Cuban is well-intentioned, his current approach will fail to significantly dent prices. But by expanding his production forays, Cuban could make real progress addressing America’s drug shortage issues.

At first glance, the concept behind Cuban’s company is perceptive. The prices of American drugs are outrageous — more than double those of neighboring Canada and more than 2.5 times the prices paid by the average of 32 high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

advertisement

Cuban’s company eliminates pharmacy benefit managers and other costly intermediaries from the drug sales process. It buys generic drugs directly from the companies that make them and sells them directly to consumers. It offers transparent, across-the-board pricing of the company’s cost of acquiring the drugs, plus a 15% markup and a $3 pharmacy service fee. Cuban claims that MCCPDC offers “the lowest prices on meds anywhere.”

But this just isn’t true; MCCPDC’s prices are not always lower than those of its competitors. MCCPDC is not the only direct-to-consumer company offering Americans generic drugs. Others include Amazon Prime, Costco, as well as the price-aggregator discount website GoodRx. Indeed, of the 211 generic drugs offered by MCCPDC that begin with the letter “A”, at least 141 (67%) were priced higher by Cuban’s company than by one or more pharmacies on GoodRx according to a 2023 analysis. A June 2024 analysis suggests that people would be better off purchasing through MCCPDC, as opposed to using their own health insurance, in less than 12% of cases for generic drugs.

The more fundamental reason Cuban’s company will not really lower drug prices much is that it deals almost entirely in off-patent generic drugs. But generics are already low-priced. On average, American generic drugs are priced 15% lower than generics in other OECD countries. These excessively low prices incentivize companies to outsource to Chinese and Indian manufacturers which lack stellar track records when it comes to quality. Lower prices also lead U.S. manufacturers to underinvest in greater production capacity to eliminate shortages. Consequently, even minor disruptions in the supply chain of active ingredients, contaminated production lines, or increases in demand, can cause the problems in drug availability Americans are experiencing today. Generic drug prices should actually be priced higher in order to encourage higher quality manufacturing of generic medications, especially those in short supply.

The drug affordability problem Cuban is aiming at lies not in generic drugs, but in brand-name drugs. Indeed, the top 10 prescription drugs by Medicare spending are all brand-name drugs, not generics.

Bringing down brand-name drug prices requires government action to lessen monopolies by either shortening the length of patent protection or by reforming patent laws that allow pharmaceutical companies to delay the onset of competitors.

If MCCPDC is unlikely to affect the cost of the priciest drugs on the marketplace, and does not offer lower prices than relevant competitors, it can still relieve Americans’ drug woes in two important ways. First, by manufacturing its own generic drugs and fixing prices based on cost of production, MCCPDC can improve transparency and expose the extent to which PBMs and other intermediaries extract value on the costly path that drugs travel between pharmaceutical companies and patients. Currently, PBMs don’t negotiate drug prices for each medication. Instead, they negotiate with both manufacturers and pharmacies for groups of drugs. This makes it almost impossible to discern the price of any one medication.

Second, MCCPDC could provide both clarity to this process and evidence of the need for increased regulation of PBMs. Regulation might include requiring transparency around PBM contracts with pharmacies, as well as providing the Department of Justice with greater resources to investigate and prosecute unfair pricing practices.

Most importantly, MCCPDC could help alleviate the shortages of generic drugs. Depressed supply of some generic medications has real-world effects, as demonstrated by nationwide unavailability of antibiotics like amoxicillin and lifesaving cancer chemotherapies. The FDA currently reports shortages of more than 100 medications. In early 2024, MCCPDC began production of epinephrine and norepinephrine, drugs routinely used in intensive care units, at a 22,000-square-foot manufacturing hub in Dallas that company CEO Alex Oshmyansky says is “designed to end drug shortages.” MCCPDC has the potential to infuse serious capital into correcting the market failure of generic drug shortages. In planning to do this in Dallas, as opposed to overseas, MCCPDC also avoids the lax production and purity standards seen in India and China, not to mention the specter of geopolitics that plagues foreign generic drug manufacturing.

While Cuban’s intentions are admirable, MCCPDC as it is presently operating is unlikely to exert systemic change in drug affordability in America. However, if used to shed light on shady pricing practices and alleviate medicine shortages, MCCPDC may yet help address America’s drug problems.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel is a physician and the vice provost for global initiatives and a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. John Connolly is a resident physician in the Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins. The opinions expressed here are theirs and no not necessarily reflect those of their employers.