Zha is a physician and a nonfiction writer.

“Been thinking about you. When are you going to start a family?” A distant friend texted me out of the blue.

“I am intentionally child-free,” I explained.

“Without children, what kind of legacy do you plan to leave?”

In recent months, the attacks on childless women have clearly escalated from devaluing our votes to questioning our worth in the world.

The sentiment that the value of someone with a uterus depends entirely on their fertility isn’t unique to politicians and abrasive friends. As a primary care physician and a medical history scholar, I have seen it echoed in medicine much too often.

Childlessness as a Disease

Plato taught that the “uterus is an internal animal subject to the desire to make children.” And when this desire is unfulfilled, the beastly organ “begins to wander throughout the body…and provokes illnesses of all kinds.” The idea of a trouble-making, nomadic, and feral uterus (“hysteria”) can be traced to one of the oldest medical texts in human history, the Ebers Papyrus.

The treatment? Pregnancy, what else! Childlessness was a disease state to be cured by childbearing.

Even today, 3,500 years later, remnants of this mythical, pseudo-scientific belief still lurks in women’s health. For instance, people suffering from endometriosis are still advised by uninformed healthcare professionals to “go away and have a baby” as a treatment or even a cure, despite pregnancy offering nothing but an illusion of improvement and a rocky road ahead.

The Uterus as a Scapegoat

Indeed, medicine still can’t look beyond uterus ownership. If a patient has a uterus, anything can be blamed on it. Thyroid disorder? You are just PMS’ing. Severe pain and rectal bleeding due to colon cancer while pregnant? Relax! Pregnancy can be uncomfortable. Appendicitis? Irritable bowel syndrome? Ruptured ovarian cysts? Any abdominal pain while having a uterus? Bad periods are just part of being a woman!

As much as we scapegoat the uterus, when the organ actually falls ill, we do a terrible job of diagnosing and treating it.

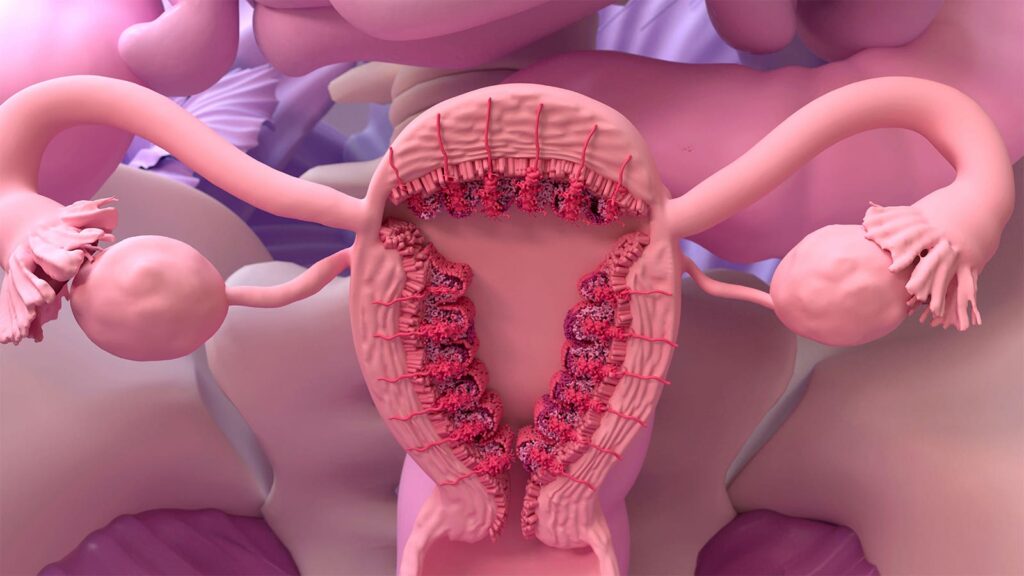

Endometriosis affects up to 15% of people with a uterus, 50% of infertility sufferers, and 70% of those who have chronic pelvic pain. Yet, with an average diagnosis delay of 6.7 years in patients ages 18-45, it has earned the title of “the missed disease.” Its treatment is inconsistent at best, if not outright lacking. Similarly, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) affects between 2% to 8% of the 1.8 billion menstruating people worldwide. Its debilitating emotional and physical symptoms are linked to a sevenfold increase in suicide attempt risk. Yet, thanks to symptom dismissal or misdiagnosis, it takes an average PMDD sufferer 12 years and six different healthcare providers to be accurately diagnosed.

Pregnancy Potential as an Excuse

A question I often repeat in my practice is: “We don’t know how safe this medication is for a developing fetus. Are you planning to become pregnant soon?”

Due to historical failures of inadequate drug studies, the FDA recommended the exclusion of women of childbearing potential from Phase I and II drug trials in 1977 even if they were on contraception. It wasn’t until more than 15 years later that Congress mandated women be included in clinical research.

Today, safeguarding a (potential) fetus is still an excuse for only a scant percentage of medication trials to focus on pregnancy-related outcomes, making pregnant and lactating people “drug orphans.” This forces clinicians like me to overestimate the harm medications have for anyone who could become pregnant, reinforcing the minimizing view of uterus owners as only prenatal, pregnant, or postnatal in the eyes of medicine.

Uterus Owners as Baby Vessels

Following this logic, the value of a uterus varies according to its candidacy as a baby vessel. My patient, Julie*, has wanted her uterus taken out due to severe bleeding and pain for over 30 years.

“You are too young,” “Your child might need a sibling,” “Your husband might want more kids,” the doctors said when they rejected her request. Now at age 45, after three kids, Julie is finally getting a hysterectomy.

“They found some shadows on my ultrasound and thought I might have cancer. Even though my biopsy was benign, the doctor still thinks it would be safer to have my uterus removed,” she told me. While Julie was OK with the decision, she was unsettled by the lack of diagnostic certainty.

The prevalence of hysterectomy for women younger than 45 is one in 36 (2.8%) in America. But by age 75, it increases drastically to 42%. As the racist history of hysterectomy abuse clings to our time, it’s no surprise that this number is the highest for Black women at any age and through more invasive means.

To be clear, as our bodies age, our body parts can fail. But no other organ is taken out at a steeper rate or more casually than the uterus once it’s deemed too old for reproduction. Performed nearly 500,000 times a year, hysterectomy is among the most common surgeries in the U.S. Not only is it the lone operation on the list of common surgeries where an entire organ is removed, but over 99% of the time it’s done for benign reasons.

Of course, “benign” doesn’t mean “unnecessary.” Many suffer from debilitating non-cancerous conditions that warrant hysterectomies (by today’s treatment protocols), and these patients have every right to receive a hysterectomy to help with their symptoms. But let’s imagine if the prostate or the testicles caused dysfunctional symptoms as much as the uterus did, and prostatectomy or orchiectomy were said to be “the standard of care,” would one in three men over 50 walk around without a prostate or testicles? Or would we have cured them with something much less invasive by now, such as a pill?

A uterus owner is more than a person attached to a uterus. Our pregnancy choices and fertility status shouldn’t dictate our healthcare. To prioritize the well-being of people over their body parts, medicine and society as a whole must look beyond uterus owners’ childbearing potential.

“My womb isn’t my legacy,” I replied to the friend, “my words are.”

*Patient’s name has been changed for privacy.

Mengyi (Zed) Zha, MD, is a physician in Washington, an author, and medical cultural critic.

Please enable JavaScript to view the