The field of Huntington’s disease research has been undergoing a radical reshaping of how the brain-ravaging disease — and what drives it — is understood. After decades focused on the notion that Huntington’s is caused by the slow, lifelong accumulation of toxic proteins produced by a mutant gene, more and more scientists are now turning to the dynamics of the gene itself.

The HTT gene, which produces a protein called huntingtin, is littered with a sort of genetic stutter — repeats of a sequence of three DNA letters: “C-A-G.” A hallmark of Huntington’s disease is that the number of CAG repeats a person has determines when in life symptoms start, if ever.

advertisement

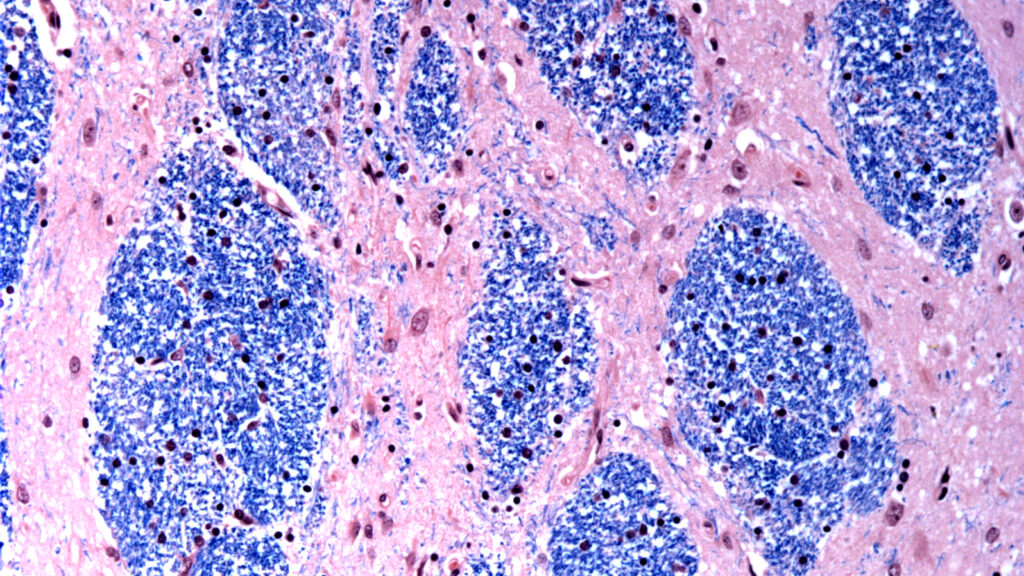

Forty or more generally result in the arrival of Huntington’s symptoms, including involuntary movements, loss of coordination, cognitive decline, irritability, and compulsive behavior, in the person’s mid-to-late 30s. All are due to neuronal death in the movement-controlling striatum as well as the cerebral cortex. More than 60 repeats can bring symptoms as early as adolescence. And the more CAG repeats there are, the more unstable the gene becomes, causing it to continue to grow over time. This “somatic expansion,” as it’s known, is what an increasing number of scientists believe is to blame for the death of brain cells.

STAT+ Exclusive Story

Already have an account? Log in

This article is exclusive to STAT+ subscribers

Unlock this article — plus in-depth analysis, newsletters, premium events, and news alerts.

Already have an account? Log in

To read the rest of this story subscribe to STAT+.