Researchers at the National Institutes of Health recently outlined strategies to tackle President Biden’s Cancer Moonshot initiative, which aims to cut cancer deaths in half over the next 25 years. They made one glaring omission: a plan to combat drug-resistant superbugs.

The two public health crises — cancer and drug-resistant infections — are deeply intertwined. Patients with cancer are three times more likely to die of an infection than patients without the disease. Unless we quickly mobilize to fight superbugs, the Cancer Moonshot will never achieve liftoff.

advertisement

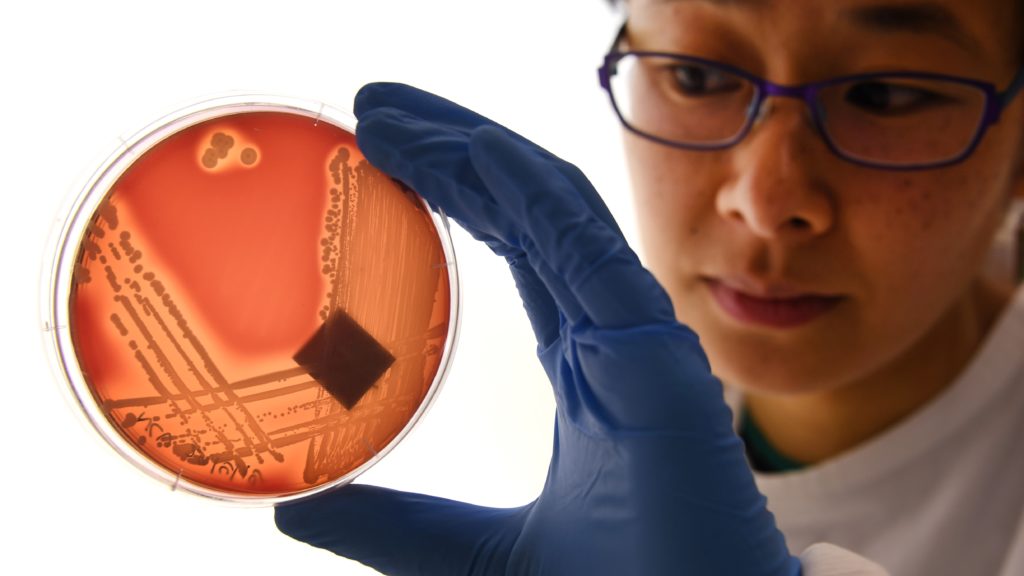

The toll of superbugs is already steep. More than 3 million Americans develop a drug-resistant infection each year, and nearly 50,000 of them die from it. And it’s getting worse.

Drug-resistant infections pose a particular threat to cancer patients, whose immune systems are weakened from fighting the disease and undergoing harsh treatments like chemotherapy and radiation.

That leaves them unprepared to fend off attacks from superbugs. While we are making advances in treating and saving the lives of people with cancer, deaths due to infection march on. And estimates indicate that infections — many of which are likely drug-resistant, though that’s rarely listed as an official cause of death — play a primary or secondary role in the death of roughly half of patients with certain types of cancer, specifically hematological malignancies and solid tumors.

advertisement

The crisis is so severe that infection is now the second leading cause of death for cancer patients, according to research published in the cancer journal CA. The same study noted that well over a quarter of the pathogens behind post-chemotherapy infections in cancer patients had evolved to resist the very antibiotics used to treat them.

Yet another study, this one from Northwestern University, determined that bacterial infections, specifically, were the most frequent type of infection for cancer patients with certain underlying malignancies.

We’ll need to develop more new antibiotics to fight off this growing threat — and accomplish the goals of the Cancer Moonshot. But that’s easier said than done.

The number of pharmaceutical companies pursuing antibiotic research has declined from 18 in 1990 to a mere five in 2020. And the number of new antibiotics approved for the market has dropped from three per year in the 1980s to fewer than one per year since 2000.

There’s a simple reason: Antibiotics are a bad investment. Discovering and marketing a new drug is a high-risk proposition in even the best-case scenario, when a company might recoup the millions of dollars they’ve invested if they manage to back a winner.

But that’s only true if the drug will be prescribed often and used for a long time. Antibiotics, on the other hand, are a last resort that doctors use sparingly and for as short a time as possible. If a drug company is looking to make a decent return on their investment (or risk going out of business), they’re not going to pick antibiotics.

Take Achaogen, a company that spent 15 years developing an antibiotic named plazomicin. Its first-year sales? Less than $1 million. Achaogen wound up filing for bankruptcy in 2019, just a year after the arthritis drug Humira racked up sales of more than $19 billion. If you were a drug company, what would you invest in?

If we want to cut cancer deaths, we can’t give up. And we don’t have to. A bipartisan group of lawmakers in Congress recently reintroduced the PASTEUR Act — a bill that can give us the upper hand we so desperately need against antibiotic-resistant infections.

Under the legislation, companies that invest in a new FDA-approved antibiotic wouldn’t have to worry about recouping their funds on the drug market. Instead, they could get payments directly from the federal government. They’d be inoculated against the market forces that have put us at a disadvantage for so long, enabling us to fight — and win — the twin epidemics of antimicrobial resistance and cancer.

There’s no time to lose. Passage of the PASTEUR Act is critical to the success of Biden’s Cancer Moonshot — and many Americans battling superbugs and cancer will enter the battle without all of the weapons needed to win.

Helen Boucher, M.D., FIDSA, FACP, is dean and professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine and Chief Academic Officer at Tufts Medicine. She was the founding director of the Tufts Center for Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance, is the immediate past treasurer of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and serves on the Advisory Board of the Partnership to Fight Infectious Disease. Kevin Outterson is the founder and executive director of CARB-X and the Austin B. Fletcher Professor at Boston University School of Law.