It was Thanksgiving 2021, and Michael Young was at Target buying a turkey baster. “I’m in the parking lot, and my chest starts to feel like somebody’s sitting on me,” Young recounted. But he didn’t think too much of it and waited until February to tell the doctor about these on-and-off chest pains. “8:30 a.m. Monday morning, the cardiologist calls me and says, ‘We have a problem; we need to talk,’” Young said. The heart scans had found lung cancer.

A 63-year-old Black man from Massachusetts, Young never smoked, but he had almost all the other risk factors. With his father in the United States military, he grew up on Air Force bases where they would use the now-banned insecticide DDT against mosquitoes. “As an 8-year-old, a whole bunch of us would chase the DDT truck down the road as it’s going on spraying the neighborhood,” Young said.

advertisement

With both of his parents smoking, there were also the 17 years of secondhand exposure. And on top of all that, in 2018, his mother got diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma, the same type of cancer Young ultimately got. Despite all the factors that put them at higher risk for lung cancer, neither of them were asked by their primary care doctors to get screened.

Lung cancer is the deadliest cancer in the U.S., with over 350 people dying from it every day — more than breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers combined. Part of the problem is that nearly half of people are diagnosed with lung cancer already in its metastatic stages, when the disease is almost always fatal. Early detection can help, but the lung cancer screening rate is just 5.7%, compared to 70%-75% for other tests like mammograms, colonoscopies, and Pap smears.

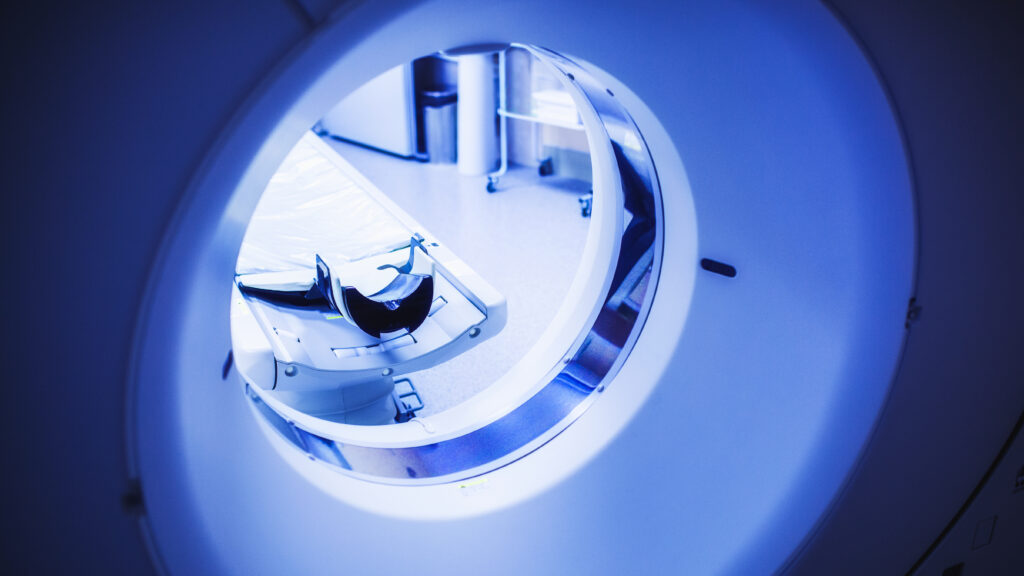

Lung cancer screening is fairly new, having been recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force only in 2013. The low-dose CT scan is quick, painless, and when combined with early treatment, can cure 80% of lung cancers, according to Claudia Henschke, a radiologist at Mount Sinai. “You don’t even have to get undressed,” she said. “The scan is just one single breath,” with radiation exposure approaching that of mammograms.

advertisement

And yet, the lung cancer screening rate has increased by only 2% over the past decade. One reason, according to several doctors interviewed by STAT, is that the screening criteria are burdensome to implement and accompanied by unprecedented insurance requirements. While other cancers require you to reach a certain age to be screened, for lung cancer, patients must currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years and have a 20-pack-year smoking history (a pack a day for 20 years, or two packs a day for 10 years, or the like).

Michael Barry, the chair of the national advisory group setting these guidelines, said the additional requirements are “an advantage to lung cancer screening.” By targeting patients with a significant smoking history, he argues that doctors can offer screening to those who need it most — in a way that’s impossible for other cancers.

But Laurie Fenton, president of the GO2 for Lung Cancer nonprofit, sees these special requirements as impractical and needlessly stigmatizing but not necessarily surprising: “Lung cancer is a redheaded stepchild.”

Smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer in the U.S. but up to 20% of diagnoses are found in never-smokers like Young. And, that share is increasing as smoking rates decline and air pollution intensifies. With the president looking to cut the overall cancer death rate by half over the next 25 years, experts told STAT that the path to success could be paved through lung cancer screening, if the test was more widely used and accessible.

Who’s eligible?

A primary care physician in Edgewood, Ky., Michael Gieske will see patients who walk into his clinic, and “you can smell the cigarette smoke, they have emphysema, they have coronary artery disease.” But what they tell him is that they’ve only smoked a couple of cigarettes a day, or maybe that they’ve already quit. Because of their guilt and shame, Gieske said that some patients filter the truth, inadvertently underestimating their lung cancer risk and making themselves ineligible to get screened.

“You’re totally dependent on the patient’s historical recollection of their smoking,” said Gieske, who compares it to asking someone how much alcohol they drink. “The old joke is you take what the patient says, and you multiply it by two. You take what the wife says, and you halve it by two.”

What makes determining lung cancer screening eligibility even more challenging is that patients don’t smoke the same number of cigarettes across their lifetime. That means calculating pack-years isn’t a simple multiplication problem but the sum of various multiplication problems, each dependent on the patient’s memory and how forthcoming they are, said Laura Zimmermann, a primary care physician at Rush University in Chicago.

Unfortunately, electronic medical records aren’t usually set up for this complexity. “Someone will come in and say they’re smoking ten cigarettes a day,” said Zimmermann. “And the next time they come in, they may say to the medical assistant, now I’m only smoking five cigarettes a day, and the assistant puts that five where the ten was,” thereby cutting the patients’ smoking history in half. “We run into a lot of data collection and documentation inaccuracies,” Zimmermann added, causing patients to fall off the radar through no fault of their own.

Both Gieseke and Zimmermann said they’ve started to address the medical records problem with new technological solutions. But with smoking and lung cancer so stigmatized, they argued that screening guidelines are still a barrier.

Barry, chair of the national task force, disputed that characterization, asserting that “our criteria for screening, which are based on age and pack years of smoking, are relatively straightforward.” However, when asked about his personal experiences as a primary care physician, Barry admitted that “getting a careful smoking history is a challenge,” and he can only do his best to pin patients down on the details and estimate their exposure. “I try to do that religiously and practice what I preach.”

‘Unprecedented’ insurance requirements

The barriers don’t just stop at the guidelines, according to David Yankelevitz, a radiologist at Mount Sinai, because lung cancer screening faces unique insurance requirements as well. Specifically, he describes how the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services mandates “shared decision making,” where providers must discuss the risks and benefits of lung cancer screening and document their discussion before it can be covered by insurance.

“I’m not against the concept that physicians should share information,” said Yankelowitz, describing how the word “doctor” is derived from “docere” — Latin for “to teach.” What he’s really against is how this mandate only applies to the low-dose CT scan and not mammograms, colonoscopies, and other screening tests, thus adding to the stigma and burden of lung cancer.

Yankelowitz also emphasized that many of the existing shared decision-making aids underemphasize the benefits and overemphasize the harms of screening, like false positives, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure — inaccurately suggesting with stick figures that patients will die 80% of the time if diagnosed with lung cancer by a low-dose CT scan. Fenton similarly described how, after hearing all the ways these aids describe lung cancer screening, “you would run screaming from the office, asking ‘Why would I do this?’”

From the primary care standpoint, Zimmerman said that taking the two minutes needed for CMS’s shared decision-making requirement can be difficult. Within an already short 15-20 minute visit, doctors have to treat hypertension, diabetes, and other diseases that patients eligible for lung cancer screening may struggle with, leaving little time for anything else. “This is, by definition, a higher risk, more medically complex population.”

Making lung cancer screening as easy to get as a mammogram

Ultimately, the debate over lung cancer screening boils down to the limits of evidence. Barry said the task force’s criteria and the shared decision-making requirement are based predominantly on evidence from randomized controlled trials, the “gold standard” of clinical research. And previous trials for the low-dose CT scan have only included people with heavy smoking histories, thus showing a benefit in this population alone. “We can only look at what we have,” he said.

But critics argue that Barry’s approach neglects other important forms of evidence. For example, since 2001, Henschke has been running a research study in New York that’s opened up lung cancer screening to anyone age 40 or older, regardless of smoking history. The way it works is that patients worried about lung cancer, whether because of family history, secondhand smoke exposure, or some other risk factor, can talk to their doctor about lung cancer screening and get a referral. A trained nurse practitioner then has a one-on-one conversation with the patient about the risks and benefits, thus shifting the burden of shared decision-making away from the primary care physician and streamlining the process.

It’s not just Mount Sinai that’s taking this approach, Henschke said — her program is part of a larger consortium of 82 institutions in the International Early Lung Cancer Action Project (I-ELCAP). Since the project started in 1994, they have screened over 90,000 people, including 15,000 never-smokers, finding one lung cancer for every 240 never-smokers screened, compared to one lung cancer per every 70 smokers.

“Clearly, you’re going to find more lung cancers in people who have a greater smoking history,” but Henschke said that’s no excuse to ignore the 20,000 Americans who are dying from lung cancer every year despite never having smoked. Ultimately, her goal is to liberalize the lung cancer eligibility criteria, driving uptake through simplicity and greater access. She told STAT, “We don’t think a randomized trial is needed” to screen people over age 40 because I-ELCAP has shown that lung cancer screening can be safely implemented, with spillover benefits beyond lung cancer to the detection of emphysema, heart disease, and other serious conditions. “As long as you aren’t doing more harm than good, and you’re finding a good number of cancer cases,” Henschke said, then why not make lung cancer screening as easy to get as a mammogram?

The majority of experts interviewed by STAT, however, didn’t think there was enough evidence to make that leap yet. “As you start to increase the range of the guidelines, you lose the benefit of going after a very high-risk population,” said Gieske, who is also the director of lung cancer screening at St. Elizabeth Healthcare. And if they expand too far, “you can reach a certain point where not only are you no longer benefiting a substantial amount of patients, but you can start harming them.” He acknowledged how much easier it would be to get his patients screened for lung cancer if the criteria were just age-based but said that can’t be the only consideration.

Fenton agreed that the data are “still insufficient” to open up lung cancer screening to a population-based strategy, but she’s excited about Henschke’s research and what her findings will continue to show since that might be the best evidence the field is ever going to get. Indeed, with the previous randomized controlled trial for lung cancer screening costing a quarter of a billion dollars, “there will never be a trial of that magnitude that would be looking at independent risk factors,” Fenton said. “It’s just not going to happen.”

The future of lung cancer screening

Since he was 35, Young has been receiving regular colonoscopies because of a family history of colon cancer, and since around 40, his wife’s been receiving regular mammograms. So, Young found it interesting that no doctor ever told him about the low-dose CT scan, despite knowing his extensive secondhand smoke exposure and that his mother had lung cancer. “It never came up: ‘Michael, you should get lung cancer screening.’”

Even in his mother’s case, Young recounts that she didn’t find her cancer through screening but by accident. “She fell in her house, and hit her chest on the stove,” Young said. The doctor ordered a chest X-ray to make sure his mother didn’t crack any ribs, and “that’s when they found her lung cancer at the size of a lemon.”

Young recognizes this is all a deadly game of chance, where he landed on the right side of the dice with his cancer found at stage 1 — but his mother didn’t and learned of hers at stage 3. But under the guidelines, lung cancer screening couldn’t have helped either of them — Young because he didn’t smoke and his mother because no doctor went through all the motions to get her screened.