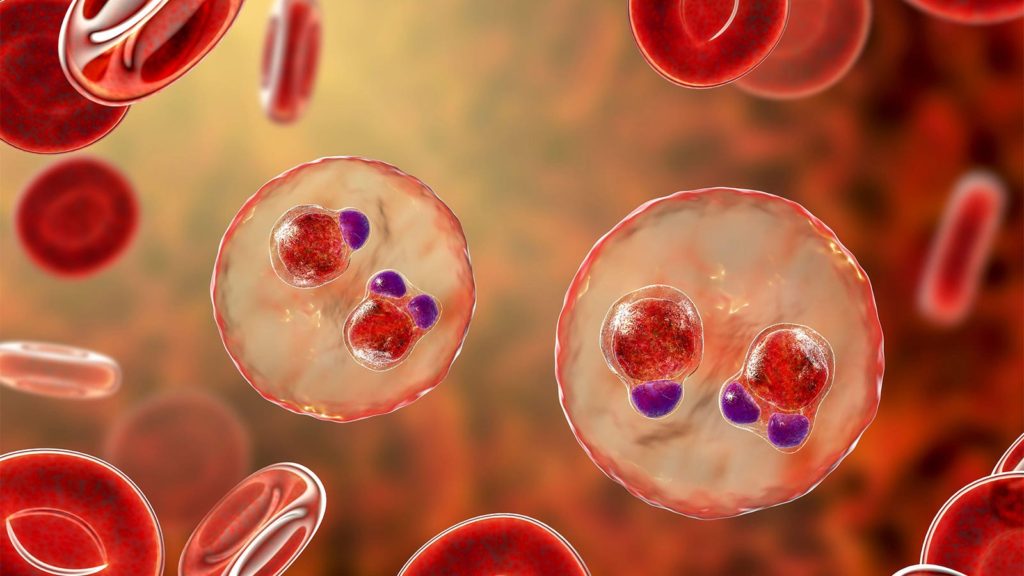

Many of the malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum parasites in some parts of Uganda are now partially resistant to artemisinin, a mainstay therapeutic, a recent study showed.

The prevalence of these artemisinin-resistant parasites reached more than 20% by 2021-2022 in 11 of the 16 districts where surveillance was conducted, reported Melissa D. Conrad, PhD, of the University of California San Francisco, and co-authors in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Specifically, the PfK13 469Y and 675V mutations were observed in far northern Uganda in 2016-2017, which increased and spread, reaching a combined prevalence of 10% to 54% across most of northern Uganda, before spreading to other regions.

In addition, the prevalence of the 469F mutation was 38% to 40% in one district in southwestern Uganda in 2021-2022, while the 561H mutation, which was previously observed in Rwanda, was first seen in southwestern Uganda in 2021, with a prevalence of 23% by 2022. Finally, the prevalence of the 441L mutation was 12% to 23% in three districts in western Uganda in 2022.

“By 2021-2022, the prevalence of parasites with candidate or validated resistance markers exceeded 20% in 11 of the 16 districts where surveillance was conducted, with foci of more than 50% prevalence in both northern and southwestern Uganda,” Conrad and team wrote.

“Our results show worrisome, sustained prevalence in Uganda of P. falciparum with artemisinin-resistance-mediating PfK13 mutations,” they added.

A prior study showed that 19.8% of P. falciparum isolates from northern Uganda tested in 2019 were carrying artemisinin-resistance mutations in the kelch13 gene, up from just 3.9% in 2015.

Many of the resistant isolates occurred in districts where effective malaria control techniques — particularly indoor spraying with insecticides that target the vector — have ceased, Conrad and colleagues noted.

In four districts in which cessation of indoor residual spraying was followed by resurgent malaria, the prevalence of any of the five PfK13 mutations increased from 8% in 2016 to 32% in 2022.

This lowered overall immunity, a finding that the team confirmed by showing that during times of control, disease burden shifted largely to older persons.

“Districts with regular indoor residual spraying from 2010 through 2014 and one additional round in 2017 had relatively low case counts and test positivity after a sustained period of spraying, with marked increases within approximately 4 to 8 months after indoor residual spraying ceased,” the authors wrote. “Increased incidence was necessarily accompanied by more frequent treatment, primarily with artemether-lumefantrine, and thus increased selective pressure for drug resistance.”

According to David Sullivan, MD, a malaria researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, “the message here is that multiple preventions are better than fewer.”

“The drugs are still working at present,” Sullivan told MedPage Today. “The higher community levels of antibodies in Uganda still help drugs work. In Southeast Asia, where kelch13 mutations are sustained, [clinicians are] doubling the duration of treating with the 3-day artemisinin combination therapy or combining it with other drug combinations. I am still optimistic for artemisinin combination therapy.”

Local clinical practices may have contributed to the rise of these mutations, Conrad’s group said. Artemisinins, derived from extracts of sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua), are an effective but short-acting therapeutic. They are usually combined with a long-acting partner drug. Since 2005, artemisinin-based combinations, typically artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine, have become standard therapies across Africa. Although artemisinin monotherapy is discouraged, the practice persists in several forms, the authors noted.

“In Nigeria, oral artemisinin monotherapies made up 2.5% of the market share among studied drug outlets in 2015,” they wrote. “The use of intravenous or rectal artesunate for severe malaria should be followed by a full course of an artemisinin-based combination, but follow-up therapy may be omitted.”

“In addition, the use of parenteral drugs, including intravenous artesunate, to treat uncomplicated malaria, although not recommended, is a well-known practice that increases the potential for selection of resistant parasites,” they added.

For this study, Conrad and colleagues looked at genetic sequences of the P. falciparum parasite in 150 isolates obtained from patients at 26 sites across Uganda from 2016 to 2022. Some of the data on these isolates were taken from previously published works; for others, the authors conducted their own genomic studies. They also looked at malaria incidence using monthly confirmed cases and test positivity from malaria reference centers, and government-instituted malaria control measures.

The investigators also compared the Ugandan mutations with the same mutations that have been documented in Southeast Asia. “The mutant parasites from Uganda were phylogenetically distant from parasites from Southeast Asia … consistent with local emergence and spread within Uganda,” they wrote.

Conrad and team noted that the numbers of samples collected per site per year were small, which limited the precision of prevalence estimates.

Disclosures

The study was funded by the NIH.

Conrad and co-authors reported no disclosures.

Primary Source

New England Journal of Medicine

Source Reference: Conrad MD, et al “Evolution of partial resistance to artemisinins in malaria parasites in Uganda” N Engl J Med 2023; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa221180.

Please enable JavaScript to view the