When Maureen Amirault purchased her first electric wheelchair in 2020, she had been living with muscular dystrophy for decades. Braces and a cane helped, but walking became too arduous, so she got a chair through a company called Numotion.

The first few months were great. The headrest fell off, but Numotion fixed it in a matter of days.

advertisement

“That was my expectation moving forward,” said the lifelong Connecticut resident. “But for the past three years, I’ve never been without a repair issue, and I’ve usually had multiple repair issues.”

Amirault hasn’t had a properly fitting footplate since she got the wheelchair. She was improperly fitted at the start, but didn’t know that her feet shouldn’t be dangling. Three years later — after dozens of texts, calls and emails with Numotion and even a personal letter to the CEO — Amirault’s footplate is still faulty.

“I’m putting all my weight on my ankles. My feet are, like, turning in and my bones are deforming. I have custom shoes, but I can’t even put those on because the foot is so curved,” she said.

advertisement

Protracted waits to get a wheelchair fixed are common for the over 5 million wheelchair users nationwide. In Connecticut, consumers wait, on average, nearly two months. Unfortunately, they are out of options as wheelchair repair technicians are highly specialized. And after buying up smaller, mom-and-pop repair shops over the last decade, private-equity-owned Numotion and National Seating & Mobility (NSM) dominate the country’s wheelchair landscape and are key figures in the $60 billion durable medical equipment industry.

The two behemoths have both been owned by private equity companies for over a decade but both got new PE owners in recent years. AEA Investors bought Numotion in 2018, and Cinven bought NSM in 2019. Wheelchair users in Connecticut say these purchases have coincided with a decline in service.

Executives at both companies say they don’t have the money to hire more people to expedite repairs and shorten wait times. However, both companies had millions of dollars in annual profits during the last few years, according to financial estimates from the research firm PrivCo.

“What we’re talking about is access to essential medical equipment that allows people to be independent and, in some cases, get out of bed. It is really problematic that the companies would claim that it’s not possible to hire more people when their profits are quite rich,” said Sheldon Toubman, an attorney for Disability Rights Connecticut.

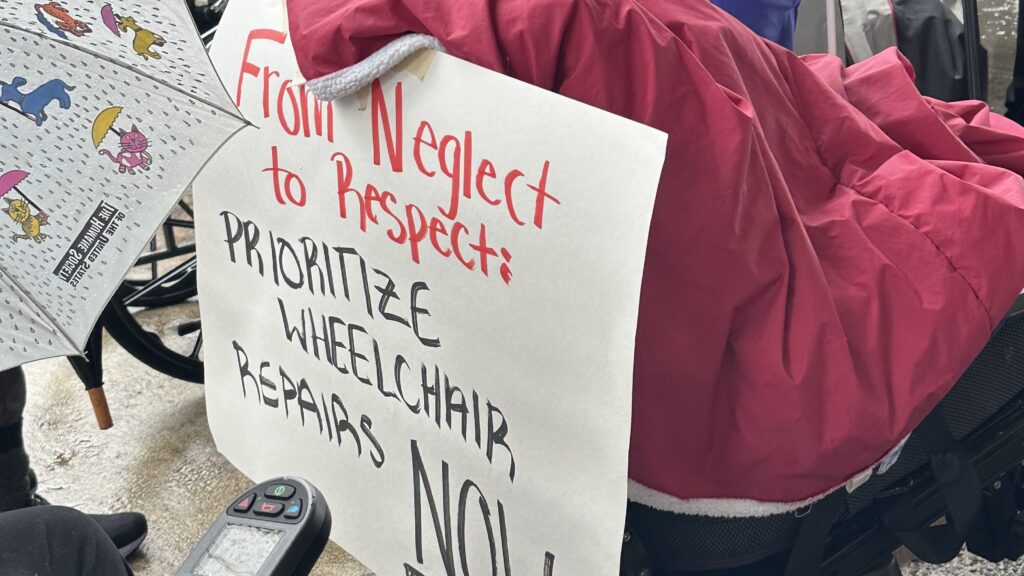

This push from disability advocates is part of a nationwide surge to secure better service for wheelchair users — especially since companies make more money selling new chairs than repairing them. Colorado recently passed a bill that allows wheelchair users to repair their own chairs, and other states, including Massachusetts, are eyeing similar measures.

“These are not isolated stories, these are common issues that people [across the country] are having, and there is a tremendous amount of frustration among wheelchair users,” says Amy Scherer, a senior staff attorney at the National Disability Rights Network and a wheelchair user.

In Connecticut, a bipartisan task force on this issue recently published a report outlining several recommendations, and Connecticut legislators have an opportunity to make some of these suggestions permanent before the legislative session ends on May 8. For the state’s approximately 6,500 wheelchair users, waiting has consequences.

“[They] said the cost is too much for them to bear,” said Amirault, referring to the reasoning the wheelchair makers offered lawmakers. “But the cost of them not [doing] it is too much for us to bear.”

The cost of long repair times

Customized wheelchairs typically last five years, but most chairs need a major repair or two during that time. Electric wheelchairs, or power chairs, are a technological marvel, meticulously designed from hub to seat to deliver power and maneuverability so the user can roam as needed, while also supporting and cushioning their body for potentially an entire day.

To get such a chair, a person needs a prescription, authorization from their insurance company, and a custom fitting from an assistive technology professional. Like a tailor crafting an exquisite suit, these technicians meticulously measure a client’s body to ensure the device’s specifications will match.

“Wheelchairs are a very personal thing. We consider them to be part of our body, and when they’re not working, we’re not working our best,” said Cathy Ludlum, a disability consultant and wheelchair user in Manchester, CT. “It’s almost like having a relationship with a doctor or a really good mechanic. You’d like to know that when something is wrong, they will be there for you. Sadly, that’s not what’s happening any more.”

A recent survey suggests the extended wait times are a widespread problem. Disability advocates conducted an informal survey that found that over 75% of consumers waited at least a month for a repair. Companies often provide loaner wheelchairs to help users get around, but they rarely fit as well. Industry experts from the National Coalition for Assistive & Rehab Technology (NCART) gave a presentation last year that showed in-home repairs took roughly two months. All this waiting has consequences for wheelchair users.

In 2021, Ludlum’s power chair frequently got stuck and couldn’t move. If there wasn’t anyone nearby to restart her chair, she would simply have to wait, often for hours. It took seven months for NSM to fix her chair.

Seven months of increased stillness sapped the strength in her hands. Ludlum, who has spinal muscular atrophy, stopped being able to reliably lift her finger off the light beam, which stops the chair. One day she couldn’t stop her chair, which then crashed into her living room couch and almost flipped over.

“It’s really scary when you can’t make your wheelchair go,” she said. “But it’s twice as scary when you can’t make it stop.”

Ludlum, 62, is quick to point out that the chair wasn’t responsible for the crash. But the experience was so harrowing that she now uses a manual wheelchair and relies on other people to push her. Years of declining service from NSM also make her reluctant to return to her old chair, which sits still in the hallway now.

Data undercut industry claims of financial hardship

While disability advocates see the wheelchair repair system as newly flawed, NCART Executive Director Wayne Grau said the dysfunction is baked in. Neither company replied to a request for comment and instead nominated Grau to speak on their behalf.

“For 30 years, the repair process has been inefficient at best,” he said. “Covid broke it with supply chain issues and with labor issues.”

Numotion Executive Vice President of the East Division Gary Gilberti blamed financial constraints at a Connecticut legislative task force meeting in November. He said, “I get the solution is more people, but that’s economically not possible.”

That narrative of financial hardship does not square with what STAT was able to find out about the financial health of both the companies. Numotion has taken home at least $90 million in profits in each of the last three years, according to estimates from PrivCo. NSM has been clearing at least $55 million each year. When asked about this data, Grau said that he was “not privy to those numbers” and reiterated that it was a “capital-intensive business.”

Industry leaders say that the keys to improving service are freeing up the supply chain, removing insurance prior authorization and getting through the pandemic repair backlog, which is significant. As of November, Numotion had 740 outstanding service orders for 622 customers and NSM had 687 for 445 customers. The companies did not offer data on the pre-pandemic backlog for comparison. However, Diane Racicot, NSM vice president of payer relations, undercut the idea that the supply chain is partly to blame, saying during a December task force meeting, “well over two-thirds of our backlog — parts are in, and we’re trying to get them out the door.”

In the wake of the task force report, the two companies promised to hire three additional technicians in Connecticut. According to Grau, they have both hired two and are both “looking for their third one.” Grau also said that wait times have improved in recent months, but when asked to share data, he did not answer the question.

Connecticut state Rep. Jillian Gilchrest recently toured the NSM warehouse in Newington and saw a cavernous room filled to the brim with roughly 200 wheelchairs, most of them waiting for repairs. Then she looked at the pictures on the wall of the staff. There were only six or eight people, and one of those workers had just left the company.

“I’m not a mathematician, but that’s not that much staff. Why can’t you hire more? Two hundred wheelchairs is a lot of wheelchairs,” she said.

Gilchrist says the script is all too familiar. As the human services committee chair in the state House of Representatives, she has watched other industries like nursing homes become dominated by private equity.

“It’s hard for me to hear that argument ‘we don’t have the money’ when their profits are so high,” she said. “I’d like to see national companies like that restructure how much they pay folks at the top and redirect some of that money towards staffing the technicians who do the everyday work.”

Most people on the task force agreed that changes needed to be made, but Gilchrist concedes that the state’s “fiscal guardrails” will likely water down any legislation.

Grau wants more wheelchair users to come into the shop, as repairs happen much faster — only two week’s wait, on average. Wheelchair users are loath to adopt this, as coming into the office can be physically treacherous for them and they would have to pay for transit. Gilchrest hopes that next year the task force can put some money into this issue, like fund paratransit to the repair shops.

Until then, Ludlum will be relying on her manual wheelchair to get around. Her world is smaller now. She can no longer visit her garden by herself, and it’s harder for her to hang out with older friends, some of whom can’t push her. She doesn’t want these subpar mobility options to close her off from loved ones, especially given the negative effects of social isolation.

“Wheelchairs and power chairs in particular make us more functional. We need to be able to move. We need to be able to go out and do things and be independent as much as we can,” she said.