- Cognitively normal older adults whose mothers had memory impairment had a higher brain amyloid-beta burden.

- Early-onset memory loss in fathers was tied to elevated amyloid levels in offspring, but late-onset cognitive symptoms were not.

- Mothers who developed memory impairment at any age — early or late in life — were more likely to have offspring with more amyloid.

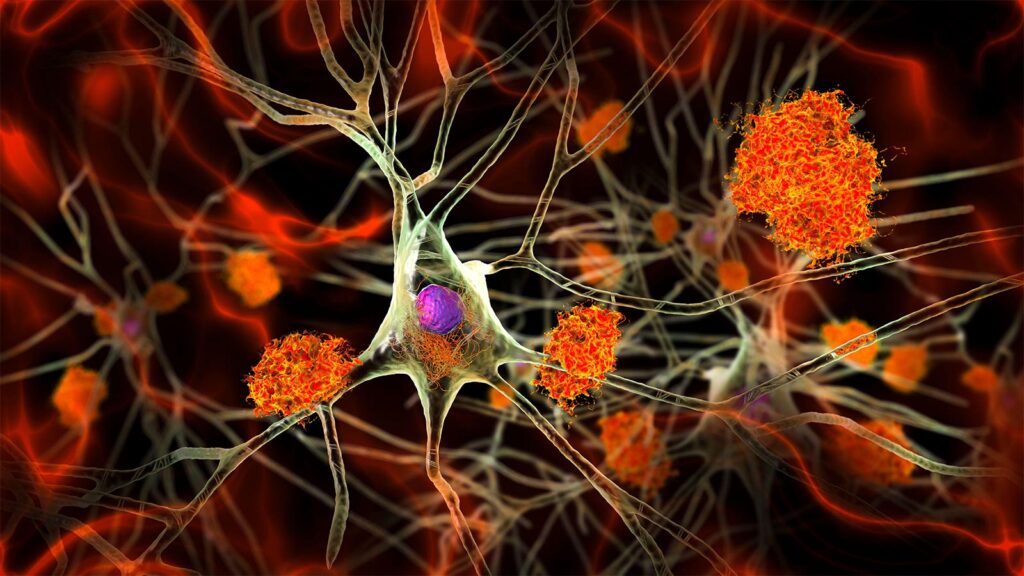

Cognitively normal people whose mothers had a history of dementia or significant memory impairment were more likely to have a higher burden of brain amyloid-beta involved in Alzheimer’s disease, cross-sectional data from the A4 trial showed.

Mean amyloid PET burden as measured by mean standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was significantly elevated among those who had memory impairment in both parents (1.12) or just maternal history (1.10) compared with those with paternal history only or no family history (both 1.08).

Maternal history of memory impairment was associated with increased PET amyloid in asymptomatic older adults whether the mother’s onset was early or late, reported Hyun-Sik Yang, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and co-authors in JAMA Neurology.

Paternal memory impairment before age 65 was tied to higher amyloid in offspring, but later onset was not.

“If your father had early-onset symptoms, that is associated with elevated levels in the offspring,” co-author Mabel Seto, PhD, also of Brigham and Women’s, said in a statement. “However, it doesn’t matter when your mother started developing symptoms; if she did at all, it’s associated with elevated amyloid.”

Mounting studies support that maternal, but not paternal, history is linked with Alzheimer’s, observed Dena Dubal, MD, PhD, of the University of California San Francisco, and Holly Elser, MD, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, in an accompanying editorial.

“Maternal transmission of Alzheimer’s disease may be rooted in biological origins related to passing on the maternal X chromosome, mitochondria, and specific genomic imprinting (or silencing of genes) to offspring,” they wrote. “Deeply understanding the maternal transmission of Alzheimer’s disease risk matters as it may unravel mechanisms at the intersection of female-specific biology, risk, and resilience in health and disease.”

Maternal history of Alzheimer’s disease in a family also results from gender disparities and secular trends, the editorialists pointed out. Generations of women with Alzheimer’s disease had less access to formal education compared with men, potentially decreasing brain reserve.

“Thus, it may seem justified, although not fair, to blame your mom for part of your Alzheimer’s disease risk,” Dubal and Elser wrote.

Yang and colleagues analyzed the family history of people who were in the A4 trial, an Alzheimer’s prevention study of investigational solanezumab in asymptomatic adults. (The anti-amyloid drug failed to slow cognitive decline.)

A4 participants were asked about the onset of memory loss in their parents, whether their parents were ever formally diagnosed, and whether there was autopsy confirmation of Alzheimer’s disease.

Data were collected from April 2014 through December 2017. All participants were cognitively normal at baseline and had cortical amyloid assessed with PET. Comparison was made against a previously published cortical composite standardized SUVR with a whole cerebellum reference region.

A total of 4,413 people were included in the analysis. Mean age was about 71, and 59.3% were women. Overall, 1,554 participants said neither parent had memory loss; 632 said only their fathers were affected, 1,772 said only their mother had memory loss, and 455 said both parents were affected.

People who said both parents had memory impairment were younger (70 vs 73 years) and were more likely to carry at least one APOE4 allele (44% vs 26%).

In sensitivity analyses, the relationships between amyloid and a maternal clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis or an autopsy-confirmed diagnosis were significant. Relationships between amyloid and a paternal clinical diagnosis or autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s were not.

The study had several limitations, Yang and colleagues acknowledged. Parental history was self-reported, and the primary definition of parental history may have captured non-Alzheimer’s causes of cognitive decline. The A4 study did not collect information about the etiology of parental dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease.

In addition, the analysis was cross-sectional and could not draw any conclusions regarding the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease over time.

-

Judy George covers neurology and neuroscience news for MedPage Today, writing about brain aging, Alzheimer’s, dementia, MS, rare diseases, epilepsy, autism, headache, stroke, Parkinson’s, ALS, concussion, CTE, sleep, pain, and more. Follow

Disclosures

This work was funded by the NIH.

Yang reported relationships with the NIH and Genentech.

Co-authors reported relationships with nonprofit organizations and industry.

Dubal reported relationships with Unity Biotechnology, S.V. Health, NIH, the Simons Foundation, the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Glenn Medical Foundation. She holds a patent for methods for improving cognition.

Elser reported no disclosures.

Primary Source

JAMA Neurology

Source Reference: Seto M, et al “Parental history of memory impairment is associated with β-amyloid in cognitively unimpaired elderly” JAMA Neurol 2024; DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.1763.

Secondary Source

JAMA Neurology

Source Reference: Dubal DB, Elser HC “β-amyloid in cognitively unimpaired individuals — blame mom?” JAMA Neurol 2024; DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.1748.

Please enable JavaScript to view the