Right now, patients with obesity and cirrhosis have few treatments for their progressive liver disease, but a new study offers one available option: bariatric surgery. Weight loss operations significantly cut the long-term risk of developing serious liver complications when compared to standard nonsurgical therapy.

The 62 patients with obesity and cirrhosis in the clinical trial who underwent bariatric surgery — either gastric bypass or gastric sleeve procedures — later had a 72% lower risk of developing more serious liver disease compared to the 106 patients who didn’t have surgery. After 15 years, 20.9% in the surgical group but 46.4% in the nonsurgical group developed one of the major complications of liver disease, including liver cancer and death.

advertisement

“We showed, regardless of the stage of disease, if we help people to lose weight, we can improve their outcomes. That can provide hope for patients and medical providers,” said Ali Aminian, director of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic and co-author of the study published Monday in Nature Medicine. “We can change the trajectory of the disease.”

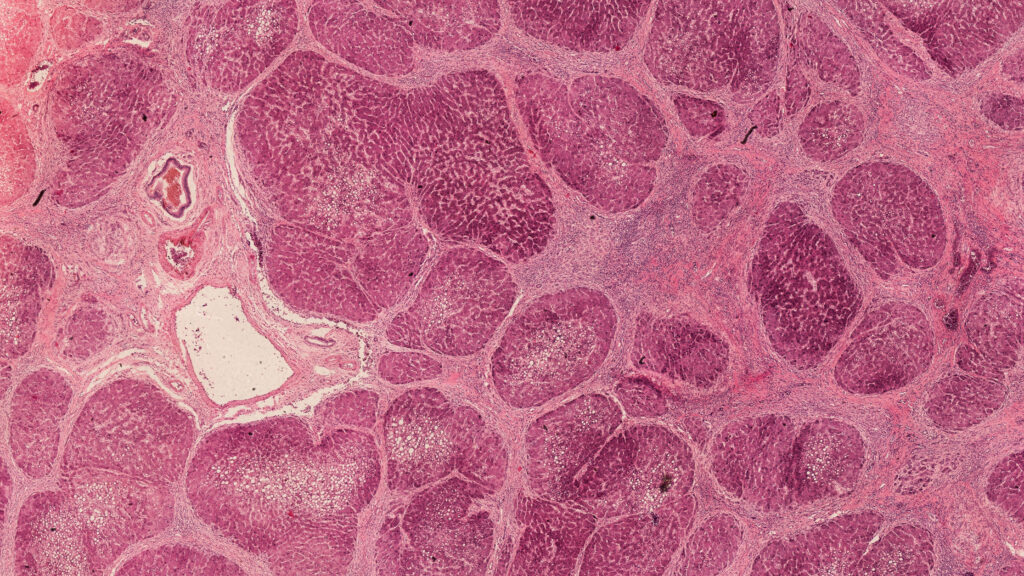

Roughly 3 million Americans are believed to have cirrhosis — scarring of the liver — caused by a disorder called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, or MASH, formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obesity and diabetes are the most common causes of MASH, which in turn is the most common chronic liver disease in the United States. When fat fills liver cells, that sets off inflammation. Liver scarring can follow, which in its late stages is called cirrhosis.

Many people don’t know they have cirrhosis. Early on it causes only vague symptoms such as weakness or fatigue that a patient might mention to a primary care provider. Blood tests and liver biopsies can confirm the diagnosis, and assign it to the first stage, known as compensated, when the liver works well enough to meet the body’s needs, Later, in the decompensated stage, the liver can’t function, so a transplant is needed for survival.

advertisement

The long, drawn-out nature of liver disease explains why it’s been difficult to clearly demonstrate clinical outcomes thus far, for new obesity drugs or other treatments, Shehzad Merwat, associate professor of hepatology and gastroenterology at UTHealth Houston, told STAT. He was not involved in the study. GLP-1s are relatively new drugs, and liver disease is a slowly progressive condition.

“It will likely take years of observation before we know liver disease-related clinical outcomes for patients who are taking medications for obesity,” he said. “Bariatric surgery may be considered in a select group of appropriate patients. Others may choose a nonsurgical approach, even in the absence of current data.”

In the new study, surgical patients in the compensated stage had an 80% lower risk of progressing to the next, more serious decompensated stage. Those patients lost 26.6% of their weight compared to nonsurgical patients, who lost 9.7%

“Weight loss is beneficial from multiple perspectives because it decreases the risks of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular adverse events,” Merwat said. “The goal is to have multiple different avenues for management, including lifestyle modifications, medical, and surgical options tailored for individual patients along the spectrum of MASH-related liver disease.”

The root cause of cirrhosis is the accumulation of fat in liver cells, so new GLP-1 drugs targeting obesity could potentially prove useful, but for now there is no medical treatment, Aminian said, beyond lifestyle interventions like diet and exercise plus simply monitoring symptoms.

“The main contributing factor is weight loss,” Aminian said. “If they lose weight by surgery or lifestyle or the medications, that’s going to help.”

There are some drugs in development specifically designed to treat MASH, but Aminian said they have a different target than weight loss. “That doesn’t do anything for the fat accumulation and metabolism and obesity but can address the fibrosis and the scar tissue formation in the liver and can reverse the fibrosis potentially,” he said. “The future is promising.”

advertisement

While the long timeframe of liver disease may make studying treatments challenging, there could be an upside to its prolonged pace, Aminian said.

From the time that fat accumulates in the liver to get to the cirrhosis, which is toward the end, takes decades. “We have a long window of opportunity to intervene to help people lose weight,” he said. “The issue is that people don’t know they have liver disease.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.