Yes, it’s possible to have a worm living in your brain — in fact, it’s far more common than you might think, said Dr. David Hamer, a professor of global health and medicine at the Boston University School of Public Health, who also directs a travel clinic at Boston Medical Center.

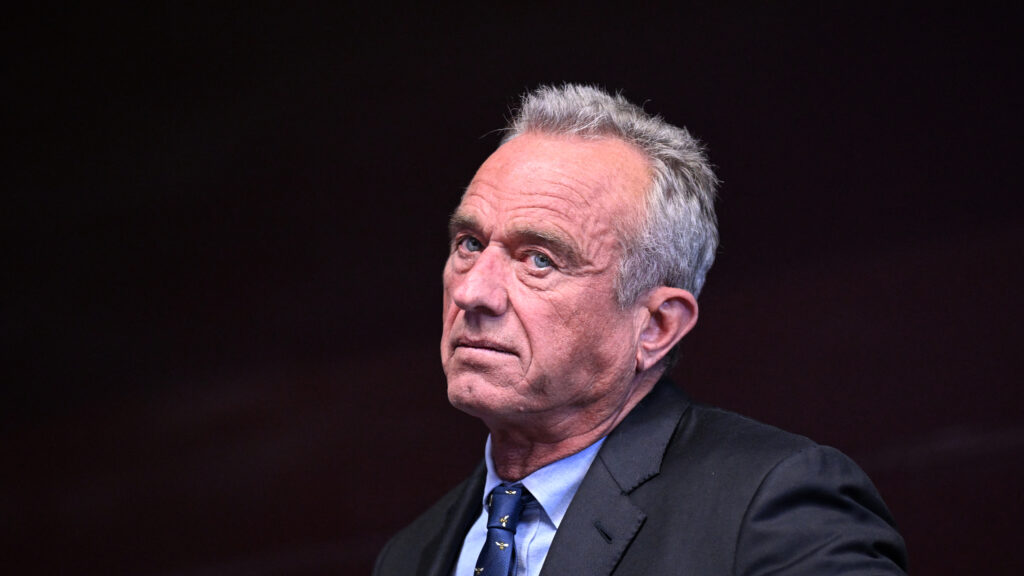

Brain worms became a topic of public fascination Wednesday after the The New York Times reported that presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was mistakenly diagnosed with a brain tumor after scans picked up abnormalities that turned out to be “caused by a worm that got into my brain and ate a portion of it and then died,” he reportedly said in a 2012 deposition reviewed by The New York Times.

advertisement

Though the article did not name the parasite involved, two doctors told the Globe the most likely culprit is T. solium, a pork tapeworm that is by far the most common brain worm.

Over the course of his 30 year career, Hamer said he has treated about 20 patients suffering from a condition called cysticercosis, a parasitic disease caused by T. solium, which accounts for the vast majority of brain worms requiring medical attention.

RFK Jr’s brain worm came to light after he experienced memory loss and mental fogginess. After brain scans revealed a dark spot, doctors diagnosed Kennedy with brain cancer and scheduled surgery at Duke University Medical Center. While packing for the hospital, however, he received a call from a doctor in New York who convinced Kennedy he’d been misdiagnosed, and actually had a dead worm in his brain, the Times reported.

advertisement

In an interview with the Times, Kennedy said he had recovered from the memory loss and fogginess and had no aftereffects from the parasite.

Cysticercosis is caused by the eggs of pork tapeworms. In most cases, someone eats food contaminated with the eggs, the eggs hatch and “sort of migrate through the body, ending up in muscles or in the brain, said Hamer.

The immune system then attacks the parasites and forms cysts around them that range in size from a couple millimeters to a couple centimeters. That can lead to irritation of the brain, which can potentially lead to seizures.

The condition is common in Latin America, where it is believed to be among the most common causes of seizures.

“It can form multiple cysts,” he said. “Some people’s brains almost look like Swiss cheese with lots of holes and there can be a fair amount of inflammation. And after many years, the parasite in there dies and the cyst will degenerate and become calcified. And at that point there’s no need for treatment.”

Medical treatment usually consists of a two-drug anti-parasitic regimen, and steroids to reduce the inflammation that usually occurs when the parasites die. Even without treatment, the parasites usually die out on their own, causing the cyst to calcify, a process that is often harmless. The condition rarely causes long-term damage.

In one famous case, an outbreak occurs in an Ashkenazi Jewish community in Manhattan, most of whom did not eat pork. The infection was eventually traced back to a Latin American domestic worker in one of the households, who had failed to wash their hands prior to preparing produce.

The disease, says Hamer, could cause the symptoms described by RFK Jr., depending on “what part of the brain it landed in and how much local inflammation there was.”

Though less common, other parasites are also a possibility. They include a flat worm contracted through wading into or swimming in some fresh water sources, predominantly in Brazil, but also in Africa and Asia. It usually infects the intestines, the liver and the bladder, and its eggs can migrate to the brain. Another type of worm is passed on by infected slugs, which shed the parasite in slime that sometimes gets onto vegetables consumed by humans and can then make its way to the brain. It can cause meningitis and has led to outbreaks in China, Southeast Asia and Hawaii. The most fatal is a brain-eating amoeba that is often contracted in warm fresh water, ingested through the nose, and often leads to encephalitis that is almost always fatal.

This story originally appeared in STAT’s sister publication, the Boston Globe.