Intraosseous vascular access for the administration of epinephrine during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest wasn’t better than going for the veins first, two separate randomized trials showed.

In the PARAMEDIC-3 trial conducted in the U.K., the 30-day survival rate was 4.5% when the first attempt at access was intraosseous and 5.1% with the intravenous-first strategy (adjusted OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.68-1.32, P=0.74), reported researchers led by Gavin D. Perkins, DSc, of University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust in England.

In the IVIO trial conducted in Denmark, intraosseous versus IV access as the first attempt had no impact on sustained return of spontaneous circulation (30% vs 29%, risk ratio [RR] 1.06, 95% CI 0.90-1.24) or 30-day survival rate (12% vs 10%, RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.87-1.56), reported Lars W. Andersen, MD, PhD, DMSc, MPH, of Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark, and colleagues.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses, as well as adverse events, were also similar between groups across trials. Both were presented at the European Resuscitation Council Congress in Athens and published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The two trials with more than 7,500 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest combined were “remarkably consistent and complementary,” according to an accompanying editorial by Niklas Nielsen, MD, PhD, of Lund University and Helsingborg Hospital in Sweden.

“The PARAMEDIC-3 and IVIO trials do not support a change in the current guideline recommendation to use an intravenous-first strategy, with intraosseous access as a secondary approach, but these trials move the certainty of evidence from very low toward high,” he concluded.

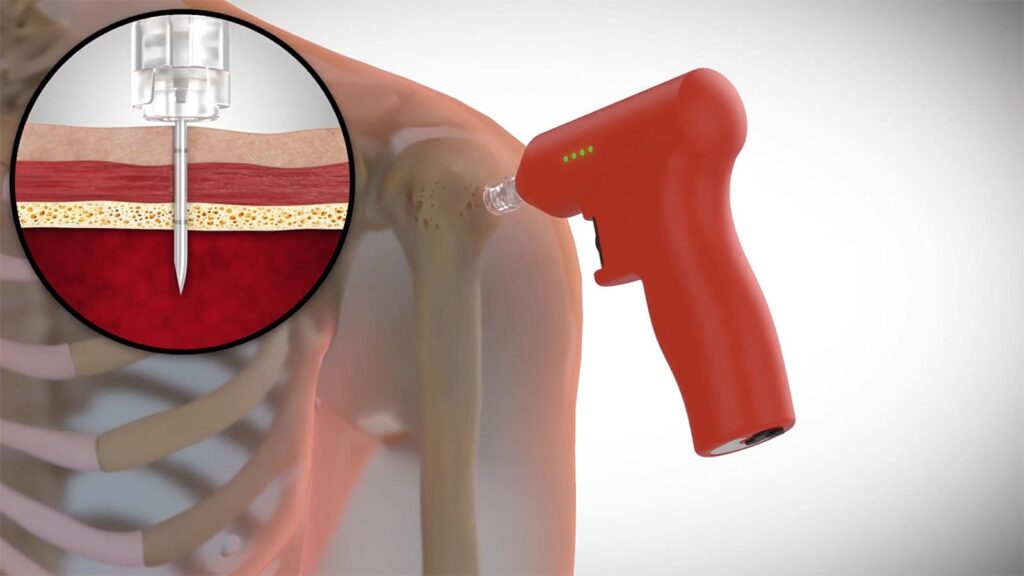

Vascular access to administer the epinephrine that boosts the chances of return of circulation and improves the likelihood of surviving to hospital admission has been part of CPR for decades, Nielsen noted. Putting the cannula in the spongy part of a bone is fast and has a higher first attempt success rate compared with peripheral venous access, but recent data have suggested neutral or worse outcomes with the former versus the latter.

In the IVIO trial, successful vascular access within two attempts occurred in 92% of patients assigned to intraosseous-first access and in 80% assigned to the intravenous-access group. The trial, conducted through emergency medical service agencies in all five regions of Denmark (typical response is by a primary ambulance unit with a physician who can terminate resuscitation on scene) included 1,506 randomized adults for whom vascular access was indicated during an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and a traumatic cause of the cardiac arrest was not suspected.

In PARAMEDIC-3, the time to vascular access and to drug administration was similar across randomized groups. The trial included 6,082 adults needing vascular access for cardiac arrest responded to by 11 emergency medical systems in the U.K.

Among secondary endpoints in PARAMEDIC-3, there was one significant advantage to an IV-first strategy: more cases with return of spontaneous circulation at any time (39.1% vs 36.0%, adjusted OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76-0.97).

“The results of the PARAMEDIC-3 trial suggest the possibility that patients who undergo intravenous access may be more likely to have a sustained return of spontaneous circulation than those who undergo intraosseous access; such a finding is important because this outcome is a prerequisite for any further favorable outcome for patients,” Nielsen wrote.

The trials had a low risk of bias, although the access route was “inherently impossible to mask for the emergency medical crews and in-hospital personnel,” he noted. “The standardized nature of CPR and the strict algorithms for termination of resuscitation would minimize any bias from a primarily unblinded intervention.” That was supported by similar results between vascular access groups in blinded assessment of neurologic outcomes in the IVIO trial.

Another limitation was that the PARAMEDIC-3 trial stopped recruitment at less than half of the “ambitious” planned sample size, Nielsen pointed out. “[H]owever, the analyses indicated that continuation toward the planned sample size would have had little influence on the final results.”

Disclosures

PARAMEDIC-3 was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme, with in-kind support from the NIHR Clinical Research Network, Health Care Research Wales, and the Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes registry.

IVIO was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Tryg Foundation, Aarhus University, the Independent Research Fund Denmark, and Snedkermester Sophus Jacobsen og Hustru Astrid Jacobsens Fond through the Danish Heart Foundation.

Perkins disclosed relationships with the British Heart Foundation, Elsevier, European Resuscitation Council, International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, Laerdal Foundation for Acute Medicine, National Institute for Health Research, Resuscitation Council (UK), University Hospitals Birmingham, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire, and University of Warwick.

Andersen and Nielsen disclosed no relevant relationships with industry.

Primary Source

New England Journal of Medicine

Source Reference: Couper K, et al “A randomized trial of drug route in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest” N Engl J Med 2024; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407780.

Secondary Source

New England Journal of Medicine

Source Reference: Vallentin MF, et al “Intraosseous or intravenous vascular access for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest” N Engl J Med 2024; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407616.

Additional Source

New England Journal of Medicine

Source Reference: Nielsen N “The way to a patient’s heart — Vascular access in cardiac arrest” N Engl J Med 2024; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe2412901.

Please enable JavaScript to view the