The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged medical practitioners on Friday to be on the lookout for people who might have contracted H5N1 bird flu from cows. The agency also urged state health departments to rapidly assess any suspected human cases, and recommended that dairy farms with confirmed or suspected outbreaks require workers to use personal protective equipment.

The recommendations were outlined in a health alert network advisory, or HAN in CDC parlance. The advisory is in response to the outbreak of H5N1 avian influenza in at least 16 dairy herds in six states across the country, which has led to at least one human infection so far.

advertisement

Health care providers should ask themselves “Could this be an H5N1 infection?” if they are faced with a patient with what CDC called a relevant exposure history — for instance, someone who works with dairy cows or lives with someone who works with dairy cows.

The illness should be considered for a range of mild, medium, and severe symptoms, from conjunctivitis to fever, shortness of breath, or pneumonia and/or organ failure, the CDC said.

Any patient suspected of having H5N1 flu should be isolated and cared for by medical professionals wearing protective equipment. Suspected cases should be started on the flu drug oseltamivir — sold as Tamiflu — even before test results confirming the infection have come back, the agency said.

advertisement

The CDC said the individual known to have been infected, who worked on a dairy farm in Texas, is recovering from very mild symptoms — effectively only conjunctivitis, sometimes called pink eye. The individual was treated with oseltamivir, as were people who had been in contact with that individual before the diagnosis. So far, there is no indication of secondary spread from this person.

“No additional cases of human infection with HPAI A(H5N1) virus associated with the current infections in dairy cattle and birds in the United States, and no human-to-human transmission of HPAI A(H5N1) virus have been identified,” the CDC advisory said.

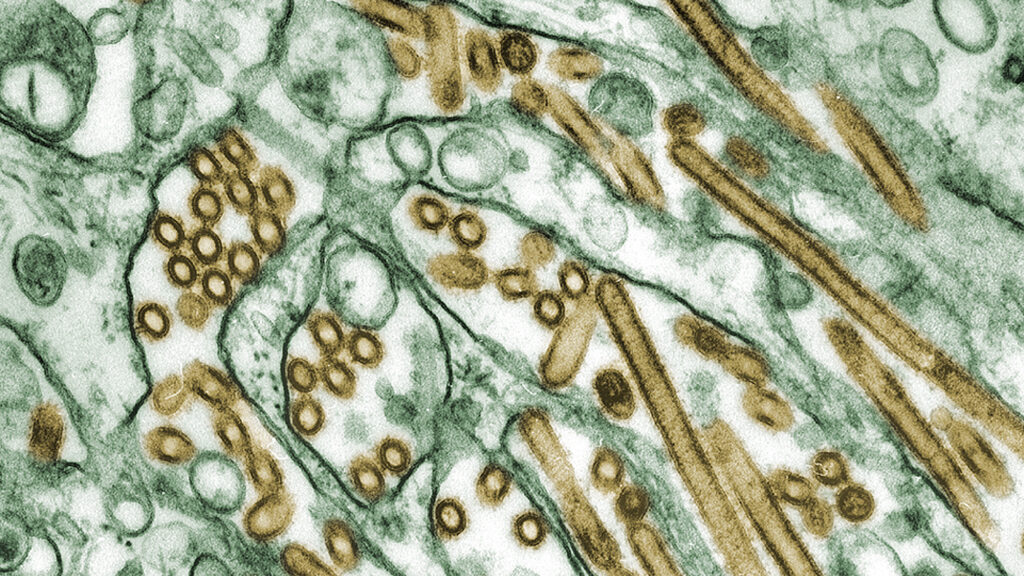

HPAI is shorthand for highly pathogenic avian influenza, a term that describes how a flu virus behaves when it infects poultry. H5N1 viruses, which have been circulating on and off since 1997, decimate poultry flocks.

In cows, however, the illness has been mild to date, with infected animals showing a decline in milk production and decreased feed consumption. Dairy operations have been instructed to destroy milk from infected animals; milk from infected animals has been found to contain H5N1 viruses.

Even if contaminated milk were to make its way into the human food chain, pasteurization would destroy the viruses, the Food and Drug Administration has said. Consumption of raw milk or raw milk cheese from infected cows could pose a health risk and should be avoided, the CDC said.

Infected cows have been reported from Texas (eight herds), Kansas (three), New Mexico (two), and Idaho, Michigan, and Ohio (one apiece).

It is unclear if the virus has been transmitting from cow-to-cow through the respiratory route, in the way human flu spreads, or whether some aspect of dairy operations — the movement of cattle from winter grazing grounds back to northern states, a lack of cleaning of milking equipment as it is moved from cow to cow — is fueling spread of the virus.

The CDC’s advisory said that analyses of viruses taken from the infected person, from cows, and from wild birds and poultry showed only small genetic changes. “While minor changes were identified in the virus sequence from the patient specimen compared to the viral sequences from cattle, both cattle and human sequences lack changes that would make them better adapted to infect mammals,” the HAN stated.