More than a tenth of fecal immunochemical tests, used for routine colorectal cancer screening, contained samples that could not be processed by labs, according to a study published this week in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

This is over twice the amount recommended by the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force, whose guidance says that for such tests the proportion of returned and unprocessed samples should not be more than 5%.

advertisement

“That sounds rather high,” said Ma Somsouk, a gastroenterologist from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in this study. Based on his previous research and a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Somsouk believes that the number should be closer to 1% of tests.

The population-based retrospective cohort study looked at the electronic health records of 56,980 individuals aged 50 to 74 who got a FIT screening between 2010 and 2019 within the Dallas-based Parkland Health System, a safety-net health system that primarily serves over 1 million uninsured, lower-income people, as well as racial and ethnic minorities. The tests were either performed in a clinic or sent through the mail.

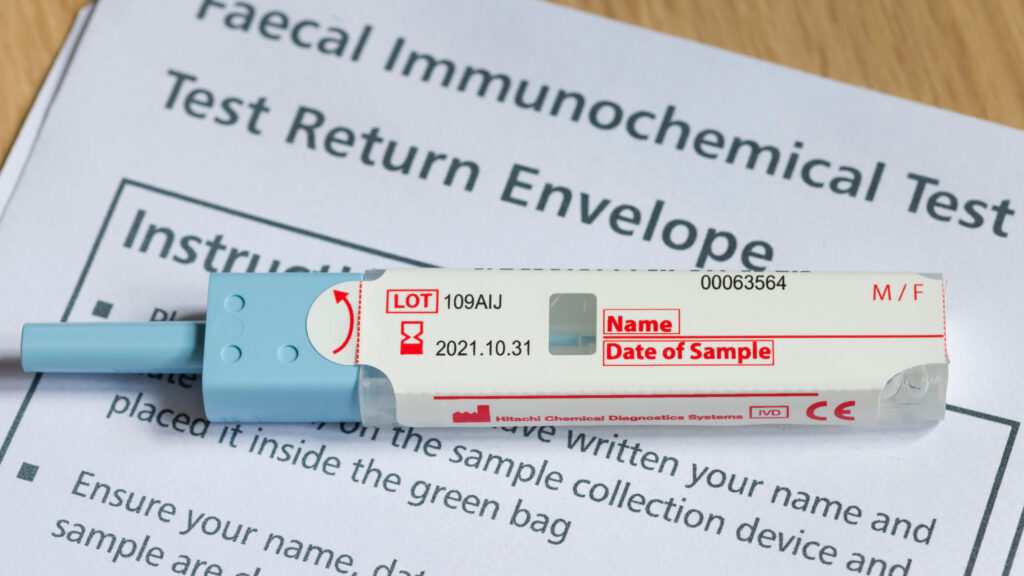

And out of the 5,819 people who had an unsatisfactory test, a little more than half had “inadequate specimen” or too much or too little stool; 27% had “incomplete labeling,” like no name, date of birth or collection date; 13% had an old sample; and 8% involved a broken or leaking container. The data also shows that only about 40% of those who had an unsatisfactory test received a follow-up test or a colonoscopy within 15 months of the failed result.

advertisement

“So, although 5,000 unsatisfactory FIT might not seem like a large number, the fact that resources including time, money and personnel are used to activate the patient to complete the FIT, and then the test could be unsatisfactory due to a preventable reason, which might not even be followed up by a subsequent test is a cause for concern,” Rasmi Nair, the paper’s co-first author said over email.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the U.S. with more than 50,000 people dying each year. The incidence and mortality rate of colorectal cancer also varies by race and ethnicity. According to the American Cancer Society, when compared to white men, death rates are 46% higher in American Indian or Alaska Native men and 44% higher in non-Hispanic Black men.

With self-collected stool tests, colorectal screenings have contributed to a substantial decline in mortality rates over the past decades. The tests, typically done at home, are also non-invasive, cheaper, and more accessible than a colonoscopy or other stool-based tests that look for potentially tumorigenic DNA, like Cologuard. This is especially true in lower-income, uninsured populations.

Even with these benefits, these at-home tests still have issues with how they were processed. Black patients were 1.46 times more likely to submit an unsatisfactory test and Spanish-speaking patients were 1.12 times more likely to get the same result. This study raises questions about the importance of minimizing language, literacy, and logistical barriers to test completion as well as the need for a system to identify and follow up on unsatisfactory tests.

FIT is a self-collected test that looks for hidden blood in the stool and is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for annual screening for individuals aged 45 to 75. “FIT is the test of choice, particularly in large population-based settings where access to screening is limited,” said Nair, an assistant professor at the Peter O’Donnell Jr. School of Public Health of UT Southwestern Medical Center. “Even when colonoscopy is available, many would prefer to do the simple, noninvasive stool test.”

Mail-ordered tests, however, were approximately three times more likely to produce an unsatisfactory result than tests performed in a clinic. The authors believe this is because individuals had difficulty understanding the written instructions, which were provided in English and Spanish, while patients in a clinical setting probably had the benefit of receiving detailed oral instructions.

At the same time, Nair and her colleagues point out that Spanish speakers were more likely to complete a subsequent test compared to other groups observed.

“So, in short, Spanish speaking patients were more engaged with their healthcare,” said Nair. “However, that could be due to cultural differences and not just health literacy.”

The authors suggested several solutions to reduce the number of incomplete and unsatisfactory tests. Wordless, low-literacy instruction or even videos would help eliminate language or literacy barriers. Newer companies include barcodes or pre-printed labels with patient information to help with labeling errors. Based on his prior research, Somsouk also suggested that labs could run the tests anyway and start including conditional statements on kits if the date is missing or overdue. This could help with a significant portion of tests with missing information, he said. “If you’re not running it, you’re not screening for cancer.”

The test being done in a single health system — as was the case with the new study — could be seen as a limitation, Somsouk added, because it only provides a snapshot of an individual health system, but other people can learn from the issues faced to improve best practices. The authors add that it could also be difficult to generalize data taken from a safety-net healthcare system.

Other limitations include the researchers’ reliance on brief notes from the laboratory explaining the reason behind unsatisfactory tests, which for example did not include additional information like was the name or date missing or illegible. And since the researchers used a 15-month cutoff for repeat testing, it is possible that a small number of tests were actually an annual repeat FIT and not related to an unsatisfactory test.

Currently, the researchers are using data from four health care institutions to understand issues with incomplete colonoscopy and subsequent testing.

“We are also working with implementation scientists at UT Southwestern Medical Center to understand current interventions for colorectal cancer screening at the system level and subsequently pilot test multi-level initiatives that can help reduce unsatisfactory FIT,” Nair said.

Overall, more studies like this, Somsouk said, will benefit the populations being screened and minimize the rate at which things are not processed. “Even a small change can make a significant impact.”