Heart failure mortality rates are moving in the wrong direction, a new analysis reports, reversing a decline in deaths that means more people in the United States are dying of the condition today than 25 years ago. The concerning conclusion comes as newer medications are raising hopes for better outcomes in the years to come.

A research letter published Wednesday in JAMA Cardiology tracked U.S. death certificate data from 1999 through 2021, revealing a steady drop in deaths until 2012, when rates plateaued, then began to rise steadily, and accelerated upward once the Covid-19 pandemic arrived. Disparities between men and women and among racial and ethnic groups moved up almost in lockstep, but there was one glaring exception: age.

advertisement

The death rate for people under 45 spiked 906% between 1999 and 2021, compared to increases of 364% for people 45 to 64 years old and 84% for those 65 and older.

“If we are moving the obesity crisis, the liver crisis, and the diabetes crisis in the United States to younger ages, which is exactly what has been going on in the last decade, that is the result of what we are observing right now: shifting the heart failure incidence curve to a younger age group,” said the paper’s senior author, Marat Fudim. He is the medical director for the Heart Failure Research Unit and Heart Failure Remote Monitoring at Duke University Medical Center. “Many of the gains, and the acceleration, would actually be attributed to the young individuals with that age under 45.”

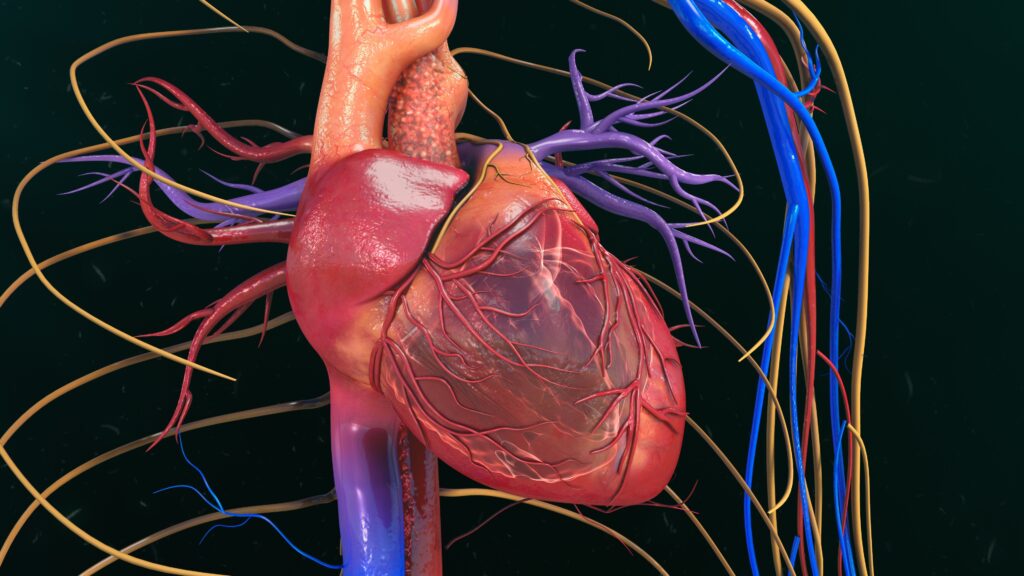

Heart failure is a chronic, progressive condition in which the heart’s ability to squeeze and then pump blood throughout the body weakens. Two main types are defined by a measure called ejection fraction. When the heart relaxes after squeezing normally, it’s known as reduced ejection fraction; when it doesn’t relax afterward, it’s known as preserved ejection fraction. Symptoms can be the same for both groups, split roughly in half, but more medications are effective in treating symptoms for those with reduced than preserved ejection fraction.

advertisement

The risk of hospitalization is higher for people with preserved ejection fraction and their quality of life is lower, often making it difficult for them to leave their homes to do basic activities like going grocery shopping or even going to the mailbox. Preserved ejection fraction tends to go along with cardiometabolic disease: obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, inactivity, “all of those things that we recognize have gotten worse over the last few decades,” said Sean Pinney, chief of cardiology at Mount Sinai Morningside. He was not involved in the JAMA Cardiology paper. “We’re seeing premature coronary disease in patients who are in their 30s and 40s, which, you know, 20 years ago would have been unheard of.”

Doctors are also seeing medications improve the prevention picture, said Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, making it more urgent to use these and other measures early to control blood pressure, blood sugar, and other risk factors. He was not involved in the study but is deputy editor at the journal.

“We need to move way upstream and think about what we can do a priori to interrupt this process,” he said about the data.

Yancy sees three explanations for higher death rates from heart failure: First, the persistence of risk factors and the necessity to intervene there. “That’s actionable,” he said. Second, the persistence of health inequities. “That is theoretically actionable, but it will require as much public policy as it will require medical therapeutics and lifestyle change.” Third is the outsized influence of Covid-19, a phenomenon he said we have yet to understand.

Over the time period covered in the JAMA Cardiology paper, doctors have gotten better at recognizing heart failure, Fudim and the other experts told STAT. Better testing perhaps contributed to increased heart failure diagnoses, reflected in the dataset from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on which the analysis was based. More people are surviving heart attacks now, so more people are living long enough to develop heart failure, which could explain higher prevalence in recent years.

There are limitations to the study’s methodology of mining death certificates, the paper’s authors note. The cause of death may not be accurate: In the case of deaths from opioid overdoses, for example, heart failure may have been cited when cardiac arrest was the cause, Mount Sinai’s Pinney said. The steeper climb in death rates coinciding with Covid could mean people sick enough to be hospitalized and later diagnosed with heart failure were suffering from infection-related inflammation as well as economic distress that limited their health and access to health care, study author Fudim said.

The data preceded wide uptake of the wildly popular new obesity drugs, developed to treat diabetes but also proven effective in improving heart health, among other conditions. These new medications appear to work for heart failure patients across the range of ejection fraction, Pinney said.

“We have to see whether or not these new medications can offset the recent worsening in cardiovascular mortality. But I think the paradox is that at a time that we’re seeing these increases in mortality, we also have access to better medications,” he said. “We need to do a better job focusing on our systems of care delivery, to get the medications to the patient. If you can get all four classes of heart failure medications into patients with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction, you can cut mortality in half.”

Northwestern’s Yancy said he was neither surprised nor sobered by the research letter’s findings.

“This really is quite the new day for those of us that have spent a career focused on heart failure,” he said. “We’ve gone from having very little opportunity to offer hope to a scenario where we can not only offer hope but we can realistically talk about true improvement.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.