- Depressive symptoms were tied to early changes in Alzheimer’s pathology in regions associated with emotional control.

- Greater depressive symptoms were associated with amyloid accumulation in frontal and cingulate cortices.

- Symptoms started at the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, before cognitive changes emerged.

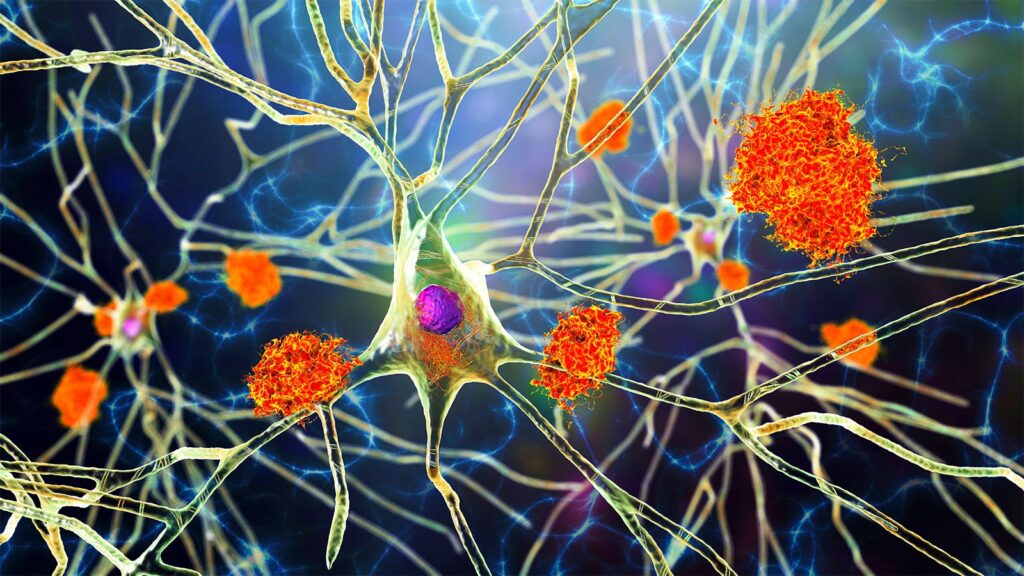

Increasing depressive symptoms were tied to very early changes in Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology in brain regions associated with emotional control, a longitudinal study showed.

In a cohort of cognitively unimpaired older adults with initially low amyloid burden, greater depressive symptoms were associated with amyloid accumulation in frontal and cingulate cortices, reported Catherine Munro, PhD, of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and co-authors in JAMA Network Open.

Over a mean follow-up of 8.6 years, increasing scores on the 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) were linked with slopes of PET amyloid burden in the following three regions, after adjusting for age, sex, and education:

- Medial orbitofrontal cortex: β=11.07, 95% CI 5.26-16.87; t=3.74, P=0.004

- Isthmus cingulate cortex: β=12.83, 95% CI 5.68-19.98; t=3.51, P=0.004

- Middle frontal cortex: β=9.22, 95% CI 2.25-16.20; t=2.59, P=0.03

These relationships were independent of cognitive changes.

The findings shed light on the neurobiological underpinnings of behavioral symptoms that occur at the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s pathological change, Munro observed.

“We report that changes in mood symptoms are associated with amyloid accumulation in specific brain regions related to emotional control starting in the earliest preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease — a stage that precedes dementia,” Munro told MedPage Today.

“Moreover, the associations between mood and regional amyloid we observe are independent of early evidence of cognitive decline,” she added. “Together, this indicates that new or worsening mood symptoms in older adulthood may be related to underlying early Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and not solely psychological reactions to cognitive changes.”

The analysis, based on a sample of 154 participants in the Harvard Aging Brain Study, aimed to determine whether early changes in depressive symptoms accompanied the earliest accumulation of amyloid in the brain, similar to what had been seen in another study of cognitive decline and subthreshold amyloid accumulation.

Previous data from the Harvard Aging Brain Study suggested a close relationship among mood, cognitive changes, and Alzheimer’s pathology in preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s, well before dementia, noted co-author Jennifer Gatchel, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “In that study, we found that global brain cortical amyloid, even at levels below what we would consider amyloid-positive, synergized with mild depressive symptoms in older adults to predict worsening cognitive performance over time,” Gatchel told MedPage Today.

In the current study, Munro and co-authors assessed PET amyloid burden over time in eight specific brain regions. PET imaging was performed at baseline and every 2 to 3 years after that. Depression was assessed annually by GDS scores, and cognitive changes were measured each year with the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite-5 (PACC). Data were collected from September 2010 through October 2022.

All 154 participants were cognitively unimpaired older adults with low amyloid and, at most, mild depressive symptoms (GDS scores under 11) at baseline. All had brain amyloid that fell below the Pittsburgh compound B (PiB)-PET detection threshold for global neocortical amyloid positivity at baseline.

Most participants (61%) were female, and 84.4% were white. Mean age at baseline was about 73. Mean baseline depressive symptom score on the 30-point GDS was 3.3.

Greater depressive symptoms over time were associated with both increasing cortical amyloid levels in three of eight regions related to mood and emotional control — the medial orbitofrontal cortex, middle frontal cortex, and isthmus cingulate cortex — and decreasing cognitive performance based on PACC scores over time. Associations between early amyloid accumulation in these three regions and depressive symptoms remained significant over time, even after adjusting for longitudinal cognitive changes.

Slopes of amyloid burden in the other five brain regions — the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, superior frontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala — were not significantly associated with depressive scores when adjusting for PACC scores.

The study had several limitations, Munro and co-authors acknowledged. The sample was selected to have low baseline cortical amyloid and a low overall burden of cerebrovascular disease. It was composed of highly educated, white older adults and results may not apply to others. Other affective symptoms including anxiety and apathy also should be assessed, they suggested.

The researchers are studying depression in other neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, Munro noted. “We hope this will guide more effective and targeted interventions for older adults with mood symptoms to improve outcomes, increase quality of life, preserve cognition and function, and ultimately prevent dementia,” she said.

-

Judy George covers neurology and neuroscience news for MedPage Today, writing about brain aging, Alzheimer’s, dementia, MS, rare diseases, epilepsy, autism, headache, stroke, Parkinson’s, ALS, concussion, CTE, sleep, pain, and more. Follow

Disclosures

This work was supported by the NIH/NIA.

Munro reported receiving grants from the Alzheimer’s Association research fellowship. Gatchel reported serving as a consultant for Eisai; receiving grants from the NIH, BrightFocus Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Association; and receiving salary support from Michael E. DeBakey Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Merck.

Co-authors reported relationships with nonprofit organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and others.

Primary Source

JAMA Network Open

Source Reference: Munro CE, et al “Change in depressive symptoms and longitudinal regional amyloid accumulation in unimpaired older adults” JAMA Netw Open 2024; DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27248.

Please enable JavaScript to view the