By its name and nature, heart failure doesn’t have a good outlook. The progressive disease is diagnosed when the heart is no longer able to pump blood and oxygen throughout the body as well as it should, limiting daily activities and lifespan. Medications have improved at easing its symptoms, including obesity drugs that appear to work by reducing weight and fat, but researchers have long sought a more direct repair of heart failure’s damage.

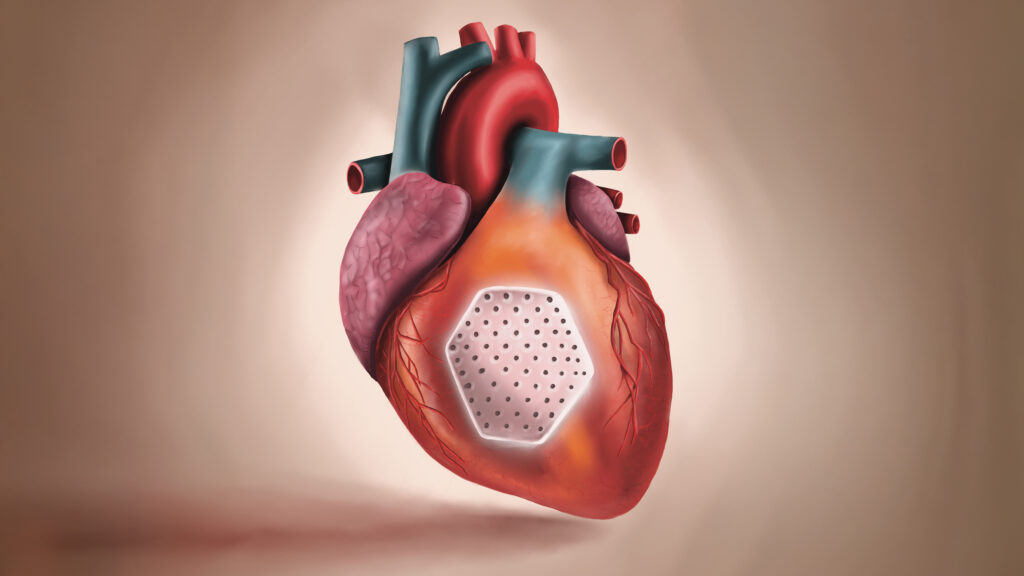

Now a lab-grown patch of heart muscle engineered from induced pluripotent stem cells may hold promise. A paper published Wednesday in Nature describes success in rhesus macaques and in one patient who later received a heart transplant. Fifteen people with advanced heart failure are now enrolled in a late-stage clinical trial led by teams at the University Medical Center Göttingen and University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck in Germany.

advertisement

“I think that the work they’ve done is really remarkable, not only in the paper, but they have been working on this system for decades and taking it forward to this point. And so doing the very careful studies in monkeys and then also getting it to humans is really a heroic achievement,” Richard Lee, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a professor of stem cell and regenerative biology at Harvard Medical School, told STAT. He was not part of the study. He added, “It’s going to take much more work to get it to the point where we’ll be excited about it clinically.”

Worldwide there are 60 million people with heart failure, 10% in advanced stages. This target population for the heart patch has only a short life expectancy after drugs no longer help their struggling hearts pump effectively, so the best treatment option at this point is heart transplantation. Available organs meet the need for only 1% of patients, and the mechanical devices people rely on while waiting have a high complication rate. Palliative care becomes the only remaining option.

“We think that we can potentially replace or at least delay the necessity for a pump implantation or even a heart transplantation,” study co-author Wolfram-Hubertus Zimmerman said at a briefing for reporters on Tuesday.

advertisement

Zimmerman, director of pharmacology and toxicology at the University Medical Center Göttingen, was cautious about calling the engineered heart patch more than a bridge to transplant, a description typically applied to mechanical pumps or other interim assistive devices, saying the ongoing clinical trial may answer that question.

“It is clear that heart transplantation is an excellent therapeutic option. The point is that we are implanting very few hearts presently, and this number will not increase, at least not dramatically,” he said. “And 99% of the patients with advanced heart failure will never receive a heart.”

The engineered heart patches, each one containing about 200 million cells embedded in a collagen hydrogel, built new muscle cells and improved the heart’s pumping function, the study found. Imaging and tissue analysis confirmed the cells’ survival amid immune suppression needed to avoid rejection. No tumors were found, a concern from earlier experiments in which cancer developed after injections of heart muscle cells were followed by such side effects as heart rhythm disturbances and tumor growth.

Lee said he was surprised by the paper’s noting that some bone cells showed up in the monkeys, which the authors wrote was new, dose-dependent, and likely related to a protocol later refined to better match the macaques.

The stem cells in the heart patches — applied singly or in combination — are off the shelf, meaning not derived from the intended recipient, which speeds their preparation. It also avoids the danger of auto-antigens developing against the implanted cells.

“This is very different from bone marrow transplantation, also very different from, for example, CAR-T administration, where blood is taken from the patient and put back relatively quickly,” Zimmerman said.

Stem cells are prized for their ability to grow into and renew themselves as heart muscle cells that graft onto weak hearts. In the study, the patches were prepared for three to six months before being implanted in macaques, where they thickened heart walls and strengthened pumping power over another three to six months.

advertisement

The cells were directed to differentiate into heart muscle cells and connective tissue cells so they could self-organize into a beating heart muscle, whose characteristics matched tissues approximately 4 to 8 years old. “While the heart is pumping, the patches are contributing, and then this translates into the pumping enhancement of the whole heart,” Zimmerman said. “This is how we interpret our findings in the monkeys and this is also what we are investigating in patients.”

In the one patient, a 46-year-old woman with advanced heart failure who was waiting for a transplant, the patch remuscularized her heart tissue. She’d had a heart attack in 2016 and developed advanced heart failure in 2021.

The engineered cells in the patch need some time to adapt before they grow and support the heart, taking roughly three to six months until therapeutic effects might be felt. That means patients, although they are sick, have to be stable when implanted.

Before trying the heart patch in this patient, the researchers and their clinical colleagues along with their ethics committee had to consider whether people treated with the patch would not be eligible for a transplant later.

“It was of course extremely important that also in the true clinical case we could confirm this bridge-to-transplant option that we have now done,” said Zimmerman.

The procedure itself is not a barrier to transplant, said co-author Ingo Kutschka, director of cardiothoracic and vascular surgery at

University Medical Center Göttingen, because it involves a small, 10-centimeter-long incision in the chest wall between two ribs through which the patch in its collagen hydrogel is applied to the beating heart. That’s less invasive than a transplant requiring the chest to be opened. “It was quite easy to take out the heart and do the transplant and the patient is fine,” he said.

The patch, Zimmerman said, is not replacing a heart transplant, but “is offering a novel treatment to patients that are presently under palliative care and that have a mortality of 50% within 12 months.”

advertisement

Lee said this kind of work is necessary to develop a revolutionary therapy.

“I don’t want patients to get excited about this, but I think scientifically, it’s really well done,” he said. “I think it’s an important step forward.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.