Would you be more inclined to take the stairs if each step played a musical note or lie in the shade on the beach if it meant accessing free WIFI These are some of the innovative ways that technology and environmental design have been utilised worldwide to help citizens adopt healthier behaviour. The speakers were: Dr Kristina Curtis, senior behaviour change consultant and lecturer, UCL Centre for Behaviour Change, UK; Prof Agnès Buzyn, executive director, WHO Academy, France; Isabelle Kumar, former Euronews anchor, carer, disability rights campaigner, president, Autisme, Ambition, Avenir, France; Koen Kas, healthcare futurist, researcher, author, founding CEO, Healthskouts, Belgium; Juhana Vartiainen, Mayor of Helsinki, Finland

Kas, founding CEO, Healthskouts, outlined examples of creative approaches to behaviour change in the session on ‘Behaviour Change: How Far Can Nations Go?’ at the HIMS22 European Conference on 15 June.

“Could nations build a healthcare environment where health comes by default?” asked Kas “I don’t have to think – it thinks for me because it’s so interwoven.”

He gave an example of the citizen-centric date platform, We Are, which is about to be launched in Flanders in Belgium, to give patients control over their health data.

“If we want the population to be healthy, we have to accept that health is a super holistic thing,” Kas told the delegates. “Health is composed of a number of things: my genome, my environment, my lifestyle and the social determinants of health. The two most determining factors that will decide how old you will get are the age of your parents when they die and your postcode.”

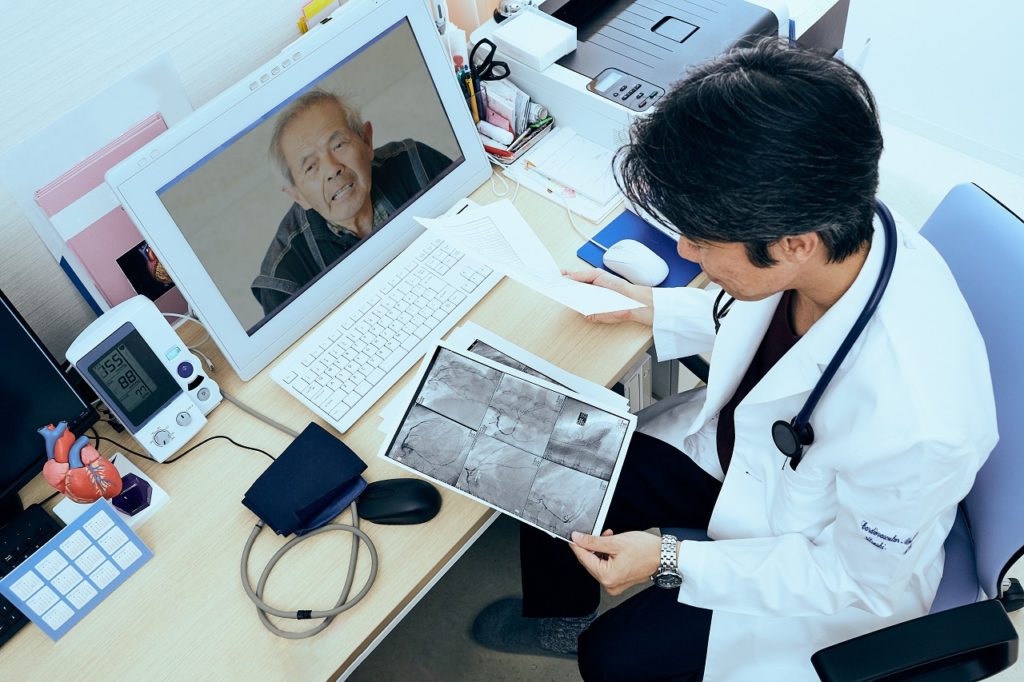

Referring to footballer Christian Erikson, who suffered a cardiac arrest at the European Championships in 2020, Kas said it was “absolutely crazy” that such a thing can happen at a time when we have the technology to prevent it.

“We can predict based on genomic profiles who will encounter this kind of cardiac arrest, so why are nations not providing it?” asked Kas. “I think it becomes ethically unacceptable not to know this, because we can simply implant a small defibrillator and if my heart stops beating it turns on.”

According to Kas, the best way for healthcare systems to encourage citizens to make behavioural change is through innovation that creates a sense of delight.

“Don’t bother about technology per se, don’t bother about what to implement first,” concluded Kas. “To start getting the best results we should start by thinking about how to create delight for citizens, patients or customers and then find the technology to do that.”

Digital education

For innovation to be effective it is also important that healthcare professionals change their behaviour. Prof Agnès Buzyn is executive director of the WHO Academy, a state-of-the art learning centre which aims to bring innovations in adult learning to global health. The centre, which is due to open in 2024 in France, will provide digital health training for healthcare professionals on topics such as cybersecurity and ethics.

“We can train health professionals to use those digital health tools as a way to help them to adapt their practice and give them incentives in their practice,” said Prof Buzyn. “This relies on the trust that citizens and professionals have in digital health tools. That means the government should build the framework to enhance trust for citizens.”

Buzyn said that France had built two main digital health tools to help implement healthcare and improve public health. The online platform Mon Espace Santé, was launched earlier this year, enabling all French citizens to access and manage their health data.

“This is something very useful for people,” added Buzyn. “We have an ethics framework around it which was co-constructed with citizens.”

Also, France has launched a health data hub which gathers health information coming from hospitals and the insurance system so it can be used for health research, to implement eHealth and improve public health.

Gaining public trust

Dr Kristina Curtis, senior behaviour change consultant and lecturer, UCL Centre for Behaviour Change, said that patients should be involved in the development process of health interventions from the start.

“It’s about understanding from a user’s perspective what’s important to them and then getting their feedback, to make sure the patient is at the heart of your intervention,” she said. “In order to change behaviour, we need to understand what the driving forces are behind that behaviour. It’s not enough just to educate people or diagnose someone with something such as being pre-diabetic.”

When it comes to how far nations can influence citizens’ behaviour without pushing too far into individual freedoms, Dr Curtis said it was important to strike a balance.

“There has to be a balance between environmental changes or behavioural nudges such as health architecture, along with allowing people to make informed choices about their behaviour and supporting them to change their behaviours at multiple layers, whether that be at the government layer, in the community or at the educational layer,” she concluded.

Healthy cities

On a local level, Mayor of Helsinki Juhana Vartiainen, said it was important for civic leaders to incentivise behaviour change in collaboration with other stakeholders.

“This is something we’ve become acutely aware of. We can make a difference in people’s behaviour,” said Vartiainen.

Helsinki is part of the WHO Healthy Cities Network, which aims to promote health and wellbeing through strategies such as providing healthy school dinners and creating safe bicycle lanes.

“Here in Helsinki, we want to improve the use of data,” said Vartiainen. “We’re thinking about using data proactively to notify people who might be suspectable to certain conditions.”