Priscilla Agnew-Hines will never be able to forget that day in early 2020. On March 26, just weeks after Covid-19 officially became a global pandemic, her son died from an overdose.

Larry, 41, was a chef, a drummer for his gospel church and the son who challenged Priscilla’s barbecue skills during summer cookouts. He also struggled with addiction. That, she knew. But what made him more prone to addiction?

advertisement

“What part of the brain triggers mental illness?” Priscilla asked during a recent interview. “If we continue to be quiet, no one will understand the process of mental illness.” So when she learned about researchers looking into the role of genetics in neurological conditions among African Americans, Priscilla was hopeful. Looking for answers, she donated her son’s brain to the study.

Priscilla was among the more than a hundred Black Baltimorians who donated the brains of their deceased loved ones for a groundbreaking initiative that’s seeking to rebuild the medical research community’s tattered relationship with Black Americans.

The study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience last month, is the first major undertaking from the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative — a collaboration between Morgan State University, a historically Black research university in Baltimore, the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, and local community leaders. Founded in 2019, the initiative has sought to understand the biological underpinnings of some neurological conditions that are more prevalent among those with African American ancestry.

advertisement

Researchers from the Lieber Institute, housed at Johns Hopkins University, found that genetics, to some degree, could explain the higher prevalence of conditions like Alzheimer’s and stroke among Black Americans, or the lower prevalence of Parkinson’s. They also speculated that environmental factors, and their impact on gene expression, might better explain higher incidence of mental health conditions like schizophrenia and depression.

The findings could someday lead to personalized therapies informed by genetic ancestry. The researchers, who worried that studies like theirs might rekindle old myths and give validity to a biological basis for race, said the focus should be on how environmental stressors and lived experiences impact gene expression. This interplay of environment and genetics could make people more, or less, prone to certain diseases.

Bianca Jones Marlin, a neuroscientist at the Zuckerman Institute at Columbia University who studies how learned information is passed down generations through genetics, lauded the researchers’ efforts to center African Americans in their study. Marlin said while the findings deepen neuroscience’s understanding of how environmental factors affect genes in the brain, she wished the researchers had zeroed in more on the impact of specific environmental factors, especially social and emotional stressors like racism, which has impacted the African American community for generations.

Still, Marlin is hopeful that the study will inspire future research to investigate how socio-emotional stressors impact gene expression, potentially predisposing Black Americans to certain diseases. By taking into account the social determinants of health, a public health concept that accounts for how biology is impacted by the environment, researchers may gain insight into the policy changes needed to improve health outcomes in the African American community.

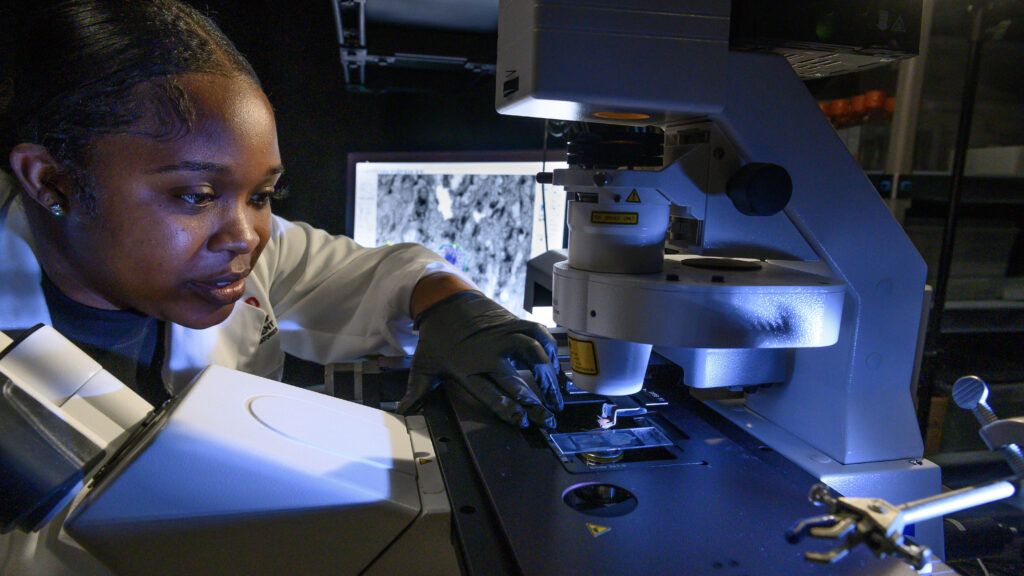

The landmark study was made possible by the more than 100 brains (and 400 tissue samples from various brain regions) from deceased Baltimorians who self-identified as African American — an achievement in itself given the long history of racism and abuse that has marked Black Americans’ relationship with biomedical research.

In the 1800s, the pseudoscience of phrenology, the idea that bumps present on skulls could identify mental capabilities, was used to justify racism and slavery. More recently in 1951, Henrietta Lacks’ cells were collected by her physician during a cervical cancer biopsy at Johns Hopkins University. Known as HeLa cells, Lacks’ fast growing cancer cells are now used extensively in biomedical research, but were first grown in the lab by her physician without her consent. And, even decades after the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which started in 1932, a majority of Black Americans still believe that “medical researchers experiment on Black people without their knowledge or consent,” a recent Pew Research Center survey found.

Whether it is due to Black Americans’ mistrust, or because they were excluded, neuroscience research cohorts are typically dominated by participants with European descent. As a result, large genetic databases commonly used in brain research are limited in their use to investigate the disparities in neurological diseases — Black Americans are 20% more likely to experience major mental health problems, and twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

In the Lieber Institute study, researchers first collected and sorted brain tissues based on self-reported race, hoping to understand how the lived experience of being African American in the U.S. impacted gene expression. Then, they determined genetic ancestry by analyzing the differences in specific genetic markers — African Americans can have a mix of African and European ancestry as a result of the long history of migration and slave trade.

To avoid playing into old stereotypes about biological differences between races, researchers sought help from Black neuroscientists. Scientists from Black in Neuro, a nationwide effort of Black scientists established in 2020 during the Black Lives Matter movement, worked closely with the researchers on how to communicate the findings.

The researchers found that environmental factors — that could include everything from water quality and air pollution, to racism — impacted neurological health outcomes among people of African descent. Structural changes to DNA mediated by environmental factors, called epigenetics, accounted for 15% of disease prevalence, while genetics accounts for 60% of differences between people of African and European ancestry.

They also found that genes that determine the body’s immune response, and the structure of blood vessels, were more likely to be elevated in people of African descent compared to people of European descent. The role of the immune system in affecting neurological diseases has recently gained the attention of the scientific community — since stress can affect the immune system, it may be the mechanism that makes some neurological diseases worse in Black Americans, a community that has a long history of experiencing discrimination.

The researchers found that genetics can explain only up to 26% of the likelihood of African Americans experiencing ischemic stroke, 27% for Parkinson’s disease and 30% for Alzheimer’s disease.

While the new findings advance neuroscience’s understanding of the disparities in disease prevalence among those with African-American ancestry, experts told STAT that the study itself is a model for more inclusive medical research.

“We reasoned that if we could demonstrate the success of this model in Baltimore (a city with a largely Black population and a long history of racial trauma and mistrust of medical institutions), we could institute a model that is suitable to be applied throughout neglected communities across the nation,” Alvin C. Hathaway Sr., who co-founded the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative, wrote in an editorial comment published along with the study.

Hathaway, who retired as the pastor of Union Baptist Church in Baltimore, was a crucial link in researchers’ ability to earn the trust of the African American community. During the 2020 racial reckoning after the murder of George Floyd, Hathaway said he realized going to protests wasn’t enough. Following a conversation with a member of the church, Hathaway decided that bringing more Black Americans into biomedical research was his new calling.

After the early success of the initiative’s first study, Hathaway is now focused on expanding the effort to more historically Black universities in other parts of the country.

For Priscilla, Larry’s mother, the study offered some closure, knowing that her son was part of an effort that could someday result in better medical care for those struggling with neurological and psychiatric conditions. She is now training to become a recovery coach, wanting to help others, like Larry, who are struggling with addiction.