As Vice President Kamala Harris emerges as the likely Democratic candidate in the U.S. presidential race, her background on health care issues ranging from reproductive rights to drug pricing is attracting more attention. A look at the life and work of Harris’ late mother, the prominent breast cancer researcher Shyamala Gopalan, offers insights into the personal connections that have shaped Harris’ views on health and medicine.

Since assuming her role as vice president, Harris has been vocal about the legacy of her mother, who died of colon cancer in 2009.

advertisement

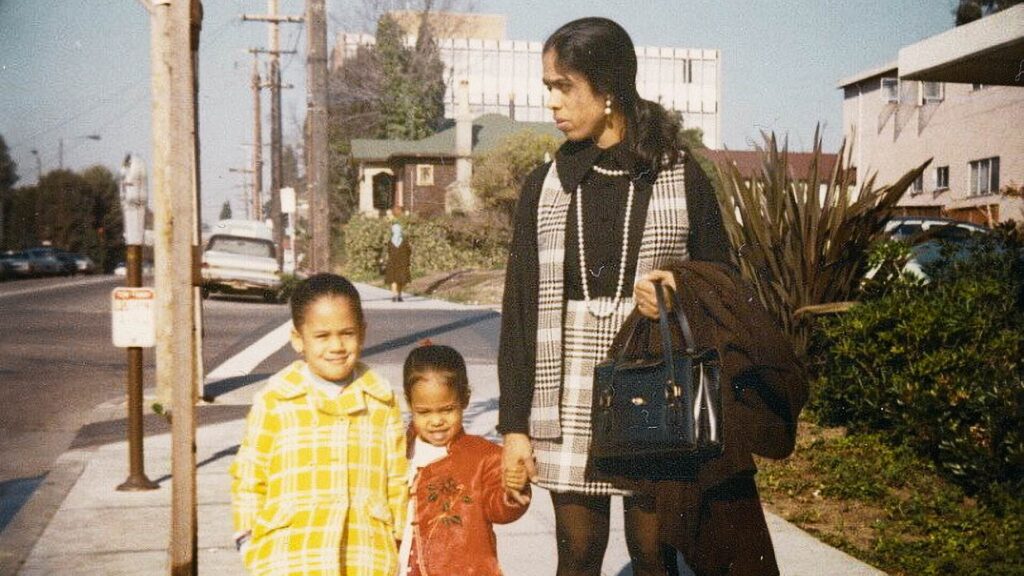

“My mother, Dr. Shyamala Gopalan, had two goals in life: to cure breast cancer and to raise my sister and me,” Harris posted on Facebook this past Mother’s Day.

Gopalan, who earned her Ph.D. in nutrition and endocrinology at the University of California, Berkeley, is best known for her research on the relationship between the progesterone receptor and breast cancer. Progesterone is the hormone responsible for the development of breast tissue and menstrual cycle regulation. Gopalan studied the misregulation of its receptor in mouse mammary glands, which provided insight into progesterone modulation in humans and how breast tissue responded to hormones more broadly.

We now know that imbalance or irregular signaling of progesterone can lead to excessive cell growth and tumor formations. Gopalan’s seminal work on hormones and breast cancer earned her an appointment on the President’s Special Commission on Breast Cancer under the Clinton administration.

advertisement

Robert Cardiff, distinguished professor of pathology emeritus at the University of California Davis School of Medicine, worked with Gopalan at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Cardiff said Gopalan would ask him to look at her animals, saying it evolved into a friendship. “She regarded me as her pathologist,” Cardiff said.

“We used to joke: she thought a thousand words were better than a picture. I thought my pictures were better than a thousand words,” he added. Cardiff added that she had a “lively sense of humor.”

The span of Gopalan’s career took her from India, where she completed her undergraduate degree from University of Delhi, to California and later to France, Italy, and Canada. In Canada, she landed teaching and research positions at McGill University and the Jewish General Hospital.

During her tenure at Jewish General Hospital, Gopalan also took on a collaboration with the National Institutes of Health. She studied heat shock proteins (HSPs) — a family of proteins overexpressed in response to environmental stresses. At the time, the proteins had been recently discovered to exist in mammals and to be produced in response to malignancy. Gopalan and her collaborators found links between hormone modulation and HSPs, implicating the importance of HSPs in understanding breast cancer.

While the partnership ended in 1992, Gopalan would go on to continue her work for the NIH as a peer reviewer. She returned to Berkeley as a researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for the last decade of her career.

In her 2019 memoir “The Truths We Hold: An American Journey,” Harris recounts how her mother’s work at the NIH shaped how she hopes to address problems in the health care system.

“I remember how proud my mother was to work with the NIH as a peer reviewer and collaborator with other experts in her field,” she wrote. “If we want our children to have cures for humanity’s most terrible diseases, we should invest in our national medical researchers, instead of relying on companies that would rather funnel money to their shareholders.”

Harris has also said that her mother’s illness changed how she thinks about health care. In a 2018 op-ed for the New York Times, Harris expressed her fears amid the news of her mother’s cancer diagnosis. “I remember thanking God she had Medicare,” Harris wrote. “I believe that health care should be a right, but the reality is that it is still a privilege in this country. We need that to change.”

Though Harris was always drawn more to the humanities and the arts, she wrote in her memoir about she was shaped by her mother’s scientific approach to questions. “When I’d ask her why something was the way it was, she wasn’t content to just give me the answer. She wanted me to formulate my own hypothesis, to use that as a starting point for further investigation, and to challenge my assumptions,” she wrote.

In public policy, Harris said, people seem to have “trouble embracing innovation. That’s in part because when you’re running for public office and you stand before the voters, you aren’t expected to have a hypothesis; you’re expected to have ‘the Plan.’”

Among the goals of the Biden-Harris administration was helping revamp the Cancer Moonshot initiative — an effort first established during the Obama administration with the goal of accelerating cancer research. At an event marking the next phase of the program in 2022, Harris commented on the importance of treating cancer in light of her mother’s work.

“When President Biden launched his Cancer Moonshot five years ago, I, of course, thought of my mother. We may not have ended cancer as we know it — not then, but there is still so much work to do and we are so much closer,” Harris said. Most recently, on July 15, the program announced upwards of $100 million will be invested in prevention, detection, and treatment of cancer in Africa.

In a 2022 post on X, Harris described the day her mother told her that she had cancer was one of the worst days of her life. “She was my inspiration and dedicated her life to finding a cure for breast cancer. I will always fight for public funding for cancer research—too many lives have been cut short.”

Cardiff described how Gopalan carried herself with strength, even when dealing with a severe autoimmune disease. “At one time she was in a full body cast, and another time she had to have an operation on her spine to hold her spine together — and whenever she talked about it she was upbeat and laughing at herself,” he said.

“She had a spirit about her that was amazing,” Cardiff added.

Beyond what Gopalan imparted to her daughters, one of her lasting impacts was on her students. “Dozens of students populated her lab through the years,” her obituary reads. “Often of color and the first in their families to pursue careers in science, these students eagerly sought Shyamala’s mentorship, which often stretched beyond the lab to encompass lessons in life.”

“One thing that struck me is that she really cared about her students and took care of them,” Cardiff said. “The last conversation that we had together before she died, she wanted me to contact several of her students to make sure that they were OK and prospering.”