A new government proposal to display nutritional labels on the front of food packaging is aimed at helping Americans make more informed choices about what they eat. An eventual side effect, research and expert commentary suggests, could be nudging the food industry to make healthier food, too.

The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday unveiled a proposal, long in the works, for a mandatory food labeling system that it says is intended to combat chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, that have been linked to excessive consumption of saturated fats, sodium, and added sugars. Sixty percent of Americans live with at least one chronic disease, and 40% live with two or more.

“We believe food should be a vehicle for wellness, not a contributor of chronic disease,” Rebecca Buckner, the agency’s associate deputy director for human food policy, said in a press briefing on Tuesday.

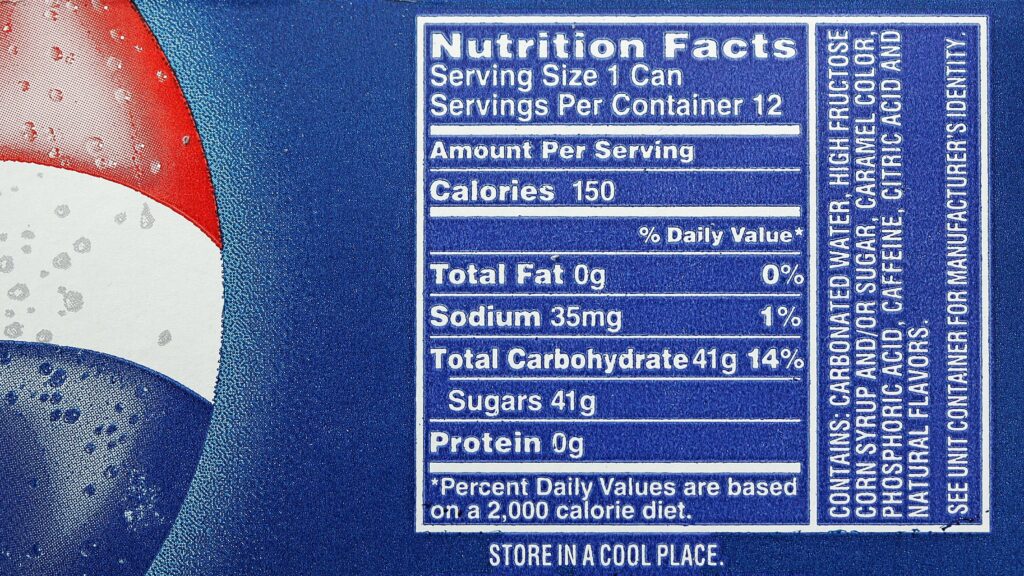

The proposed label is a black-and-white box that shows the percentage of the daily recommended amount of sodium, added sugar, and saturated fat included in a serving, and rates whether a serving has a “low,” “medium,” or “high” level of each nutrient. The FDA says the ratings could incentivize manufacturers to reduce levels of those three nutrients, although that’s not the agency’s goal in proposing the change. “We assume there may be manufacturers who would want to reformulate to move from the high to the medium category, or from the medium to low category,” Buckner noted.

advertisement

The proposal is open for public comment for the next three months. What happens next will be up to the Trump administration and quite possibly to Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who’s pledged to take on the food industry as part of his Make America Healthy Again movement if he is confirmed as the new head of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Reactions to the proposal from nutrition experts and the food industry so far are mixed, with both groups objecting to the design of the food label for different reasons. But research does show that when countries around the world introduce new food labels, it can spur manufacturers to change their practices.

“When you get mandatory systems, you do see shifts in industry trying to lower the amounts of added sugars or sodium or saturated fats to get under those thresholds to avoid a warning label,” said Christina Roberto, an associate professor of health policy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine who has studied the impact of food labeling requirements.

That said, she noted, the effects are not always straightforward. The food industry has been lowering the amount of added sugar in products in recent years, but that’s meant introducing more sugar substitutes like aspartame into the food supply. “There is reason to be concerned about that,” she said. “You don’t want to cause some other unintended consequences.”

How will the food industry respond?

If the rule is finalized under the incoming Trump administration, manufacturers with $10 million or more in annual food sales would be required to comply within three years of its effective date, and smaller manufacturers would have to comply within four years.

advertisement

Food industry trade groups appeared poised to push back on at least some elements of the proposed label, particularly the fact that it focuses exclusively on nutrients that are consumed in excess rather than also including healthy nutrients, like fiber.

“The FDA’s proposed rule for front-of-package nutrition labeling appears to be based upon opaque methodology and disregard of industry input and collaboration,” Sarah Gallo, senior vice president of product policy at the Consumer Brands Association said in a statement.

The label’s focus on just three nutrients is “overly simplistic and will not help educate consumers on how to improve their overall dietary pattern,” said Jennifer Hatcher, chief public policy officer of the Food Industry Association trade group. However, she said the group appreciated that calories could be voluntarily included alongside the label, as well as “the agency’s decision to maintain a black-and-white FOP labeling scheme and to include at least some quantitative values.”

By contrast, the FDA’s announcement was welcomed by the advocacy group Center for Science in the Public Interest, which — along with the Association of SNAP Nutrition Education Administrators and the Association of State Public Health Nutritionists — filed a petition in 2022 calling on the agency to instate mandatory front-of-package labeling.

The nutrition label “will provide information that can help people make healthier choices” and is “certainly an improvement over the status quo,” said Eva Greenthal, a senior policy scientist at CSPI.

Still, the formatting of the label is already proving controversial, with some health experts, including Greenthal and Roberto, saying evidence shows a so-called “high-in” warning label — which warns people that a particular product is high in sodium, saturated fats, or sugar — is easier for consumers to understand at a glance.

The proposed label, which lets people know whether the food has a high, medium, or low of each of the three nutrients, “can be confusing to consumers,” said Roberto. “It’s like pulling up to a traffic light that’s red and green at the same time and you don’t know what to do. It’s low in sugar but it’s high in sodium — is it good, is it bad?”

Dariush Mozaffarian, a professor at the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, applauded the FDA’s recently updated definition of “healthy” food, but said that focusing on ingredients like saturated fats and sugar represents a “very 1980s” throwback to a more simplistic understanding of nutrition science.

“You can’t define a food based on just a couple of nutrients, it leads to mistakes and Frankenfoods and misdirection,” said Mozaffarian, citing the example of the low-fat craze of the 1990s, which left the U.S. awash in SnackWells cookies and olestra potato chips.

advertisement

If food companies reformulate their products in response to the labels, he said, “you’re going to get starch-rich, artificially healthy products and not minimally processed foods high in healthy ingredients.”

What the research shows

There are, however, some hopeful signs of how the food industry has responded to labeling initiatives in other countries. Manufacturers are often incentivized to lower the amounts of sugar and salt in packaged foods in order to stay under certain nutritional thresholds, according to a 2021 paper published in the Annual Review of Nutrition.

One instructive example is Chile, which in 2016 began requiring that foods display warning labels on the front of their packaging if they met the threshold for having high levels of sodium, added sugars, saturated fats, or calories.

Within a year of the law’s implementation, the proportion of packaged foods that had high levels of sugar fell from 80% to 60%, and the proportion of foods with high levels of sodium dropped from 74% to 27%, according to a 2020 study. In most cases, the new levels of nutrients fell just below the threshold for a warning label.

The law was less successful in nudging the food industry to decrease levels of saturated fats in their products, which the authors suggest may be because saturated fats were technically harder to replace. “Saturated fat is a lot more challenging, especially for things like mouth feel,” said Roberto.

The food industry could also get around the label’s intended effect by reducing serving sizes, said Montserrat Ganderats-Fuentes, a researcher in food policy and public health at Arizona State University. “That could create misunderstandings and maybe not induce the food industry to reformulate.”

Food companies can be hesitant to reformulate because they fear customers will reject an unfamiliar taste. (See: New Coke.) But on the upside, labeling systems can spur companies to develop new, healthier products that do meet requirements, Ganderats-Fuentes said. That’s what happened in both the U.K. and the Netherlands, with one study finding that 29% of products bearing the Netherlands’ healthy food designation were introduced after the program was implemented.

Ideally, experts say, policies like this are a way the FDA can indirectly influence industry practices while operating within its legal authority. “People don’t even need to change their individual behavior,” said Greenthal. “The food supply just gets healthier, and we all benefit.”

advertisement

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.