The opioid and overdose crisis is a national tragedy, claiming more than 1 million lives since 1999. In the past three years, more than $55 billion has flowed into state, county, and city coffers from opioid manufacturers, distributors, and chain pharmacies as a result of their collective role in instigating and perpetuating this public health crisis.

This urgently needed infusion of funding has the potential to turn the tide on the epidemic. Here in Rhode Island, where we are current and past members of the Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee, the state has quickly gotten money out the door, investing in prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm reduction programs, including the nation’s first state-authorized overdose prevention center. While states should move as quickly as possible to fund evidence-based programs that save lives, we must also learn the lessons from past master settlements and acknowledge the limitations of dollars alone in addressing this complex public health crisis.

advertisement

History tells a cautionary tale of how public health funds can go misspent. After the high-profile case on big tobacco, the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement was seen as a true win to support a community harmed by smoking and misinformation. Unfortunately, however, only a very small percentage of the money went to public health programs: In fiscal year 2023, the states collected an estimated $26.7 billion from these settlements, but only 3% went to programs to prevent children from smoking and to help individuals quit. As a result, progress has stalled: Tobacco smoking is still responsible for more than half a million deaths each year, a number that has not declined.

Now that seems to be happening again. There are nationally recognized guidelines for spending these funds, which include using scientific evidence to inform spending decisions. But many states have wide discretion in using opioid settlement funds. Funds are already going to ineffective strategies like bolstering police budgets and buying drug disposal pouches (in theory to prevent diversion of prescription medications), while other communities continue to endlessly debate where the money should go.

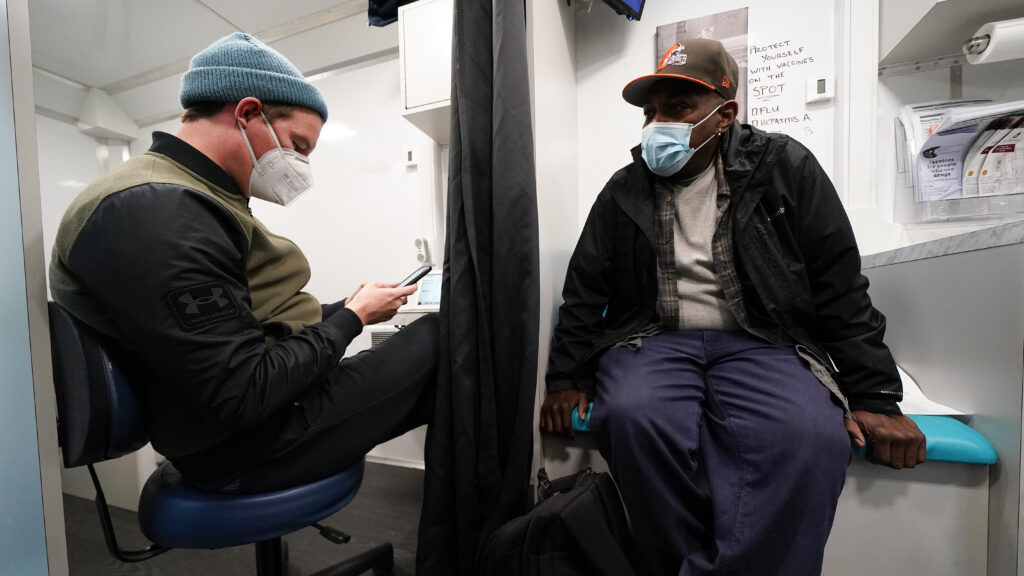

In Rhode Island, we have worked to ensure transparency in spending decisions that invest in evidence-based solutions. This work includes close partnership with community organizations, multiple interdisciplinary task force committees, utilizing public meetings and forums, and working to incorporate people with lived experience in the decision-making processes. We have developed a public website to track opioid settlement spending. Funds have supported mobile outreach, a 24/7 buprenorphine hotline, access to medications for the uninsured, low-threshold housing for people who use drugs, a racial equity working group, and expansion of naloxone distribution efforts. And unlike many states, Rhode Island has relatively easy access to low-barrier treatment programs, a high per-capita rate of opioid treatment programs, and a robust treatment infrastructure for its jail and prison population. These programs likely contributed to the recent 7.3% decline in overdose death rates in 2023 from 2022 in the state, including a notable decline in deaths among Black and Hispanic/Latino Rhode Islanders for the first time since 2018.

advertisement

Despite the infusion of money, one of the few residential treatment programs for women in Rhode Island closed due to financial struggles. There are no inpatient treatment facilities for pregnant women in the state. Nationally, addiction-related services face low Medicaid billing rates and limited insurance coverage of lifesaving medications. Challenges in workforce development create ubiquitous staffing struggles.

And though the state broadly supports an overdose prevention center and other progressive efforts, stigma against harm reduction persists, as does an over-reliance on the criminal justice system to serve as a de facto safety-net treatment facility for people with addiction — one that, of course, does not work.

Some states, including our home state of Rhode Island, offer valuable lessons.

First, accountable distribution of money is only the first step. Governments must also accurately design requests for proposals, ensure efficient procurement systems, evaluate programs effectively, and streamline execution of funding ideas or this is all for naught. We have seen firsthand that bureaucratic processes can be extremely difficult for small organizations to navigate. That is why it is important to invest in capacity-building and support for grassroots organizations that are on the front lines of the overdose crisis.

Second, throwing money at the problem cannot be the only strategy for improvement. This is equivalent to trying to fill a bucket full of holes — no amount of treatment programs will suffice if people’s basic needs remain unmet. To truly address the crisis, settlement funding needs to be paired with meaningful policy changes that rebuild our social safety net, address our housing and affordability crises, and provide real economic opportunities to people struggling with substance use.

Some recent policy changes at the federal and state level should be applauded. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recently increased flexibilities in methadone access and take-home capabilities and identified harm reduction as a core pillar of the overdose prevention strategy. New York City has implemented two overdose prevention centers with great success: In the first year of operations, more than 2,800 people accessed the site and more than 75% received other wrap-around services. Rhode Island, Minnesota, and Vermont have begun to support these evidence-based interventions. Tele-prescriptions of buprenorphine have become normalized. And the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has encouraged Medicaid 1115 waivers to provide insurance coverage to individuals prior to release from jail and prison to support the period of reentry, an extremely high-risk period for opioid overdose.

advertisement

Yet regressive policies have gained momentum elsewhere. State Opioid Treatment Authorities are not required to adopt the new federal flexibilities, and many haven’t. Buprenorphine telehealth prescriptions regulations are not permanent. Kentucky is even considering reducing physicians’ ability to prescribe buprenorphine. The nation still lacks enough clinicians willing to prescribe treatment and a large enough workforce to build a truly robust addiction treatment infrastructure. And the recent Supreme Court ruling in Grants Pass vs. Johnson may open the door to more tent encampment clearances, which have been shown to increase mortality for people who struggle with opioid use and are unhoused.

Third, we’ve learned that addressing the longstanding, pernicious racial/ethnic inequities in access to prevention, treatment, and harm reduction services must be at the forefront of every opioid settlement funding decision. Black, Indigenous, and other people of color have for too long been neglected by our health care and treatment systems as a result of stigma and racism. We will not solve the overdose crisis until we address the structural racism built into the addiction treatment system, in which access to lifesaving medications is determined in large part by a patient’s race and ZIP code. Unless states and other jurisdictions meaningfully incorporate addressing structural racism as a guiding principle of opioid settlement funding decisions (as Rhode Island and others have done), these resources could very well increase existing inequities (by driving even more resources to predominantly white communities).

Finally, settlement funds must be leveraged to address the rapid increase in stimulant-involved overdoses, particularly in Black and Hispanic/Latino communities. Here in Rhode Island, almost two-thirds of all overdose deaths among Black residents involved crack and/or cocaine (compared with less than 40% among white residents). In addition to supporting treatment programs for stimulant use, funds should be used to support culturally-tailored, multilingual outreach to BIPOC communities to increase access to lifesaving harm reduction services.

advertisement

Engaging community stakeholders is essential. By partnering with community organizations, front-line workers, and people with lived experience, we can ensure that funds are spent wisely and effectively. These voices must be at the forefront of decision-making processes, providing insight into what works on the ground.

Increasing reimbursement rates for addiction and social services is critical for sustainability, as adequate funding will prevent financial struggles and program closures, enabling vital services to thrive and provide reliable support. Expanding workforce development is necessary to ensure timely access to care; we need to leverage opioid settlement funds to train more health care professionals addiction treatment and harm reduction to build a strong treatment infrastructure. It is also crucial to maintain and expand federal and state policies that reduce barriers to treatment. Recent steps, such as increased methadone access, tele-prescriptions of buprenorphine, and Medicaid 1115 waivers for reentry support, must be preserved and more widely adopted.

And the governance of these efforts and programs must be conducted in an efficient and streamlined manner that minimizes unnecessary bureaucracy yet maximizes accountability and evaluation.

Throwing money at the problem will not be a panacea and the settlement funds will eventually run out. Nevertheless, they do represent a once-in-a-generation opportunity to support real solutions to the nation’s overdose crisis.

Justin Berk, M.D., M.P.H., M.B.A., is an assistant professor of medicine, pediatrics, and epidemiology at Brown University. Dennis Bailer is Overdose Prevention Program director at Project Weber/RENEW. Brandon D.L. Marshall, Ph.D., is a professor of epidemiology at the Brown University School of Public Health. The perspectives shared in this piece are those of the authors and do not represent the views or opinions of the Rhode Island Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee, nor the state of Rhode Island.

advertisement