A new report released Thursday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention appears to show that Lyme disease cases in the United States rose by 69% in 2022 over previous years. But in reality, the sharp increase is likely due to a new way of doing surveillance for the disease, not an explosion of cases.

The change, an attempt to lift a crushing reporting burden off the shoulders of states where Lyme disease infections are common, went into effect in 2022. From that point forward, 15 states that historically have reported about 90% of all Lyme disease cases now need only a positive blood test result to report a case to the CDC. States where the disease is rare must still gather clinical data on each person who has a positive Lyme test before reporting it as a case.

advertisement

In 2022 using the new surveillance approach, 62,551 Lyme disease cases were reported to CDC. That is 1.7 times the annual average — 37,118 cases — that were reported during the period between 2017 and 2019.

The new approach is a recognition of two facts: There are a lot more cases of Lyme disease in the country than are ever reported to the CDC, and the previous approach to counting cases was putting far too much work on public health departments in high-incidence areas.

“So we’re capturing a bigger piece of that pie. And we’re saving them time,” said Kiersten Kugeler, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s Division of Vector-borne Disease. Kugeler is first author of the article, published in the CDC’s online journal Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

advertisement

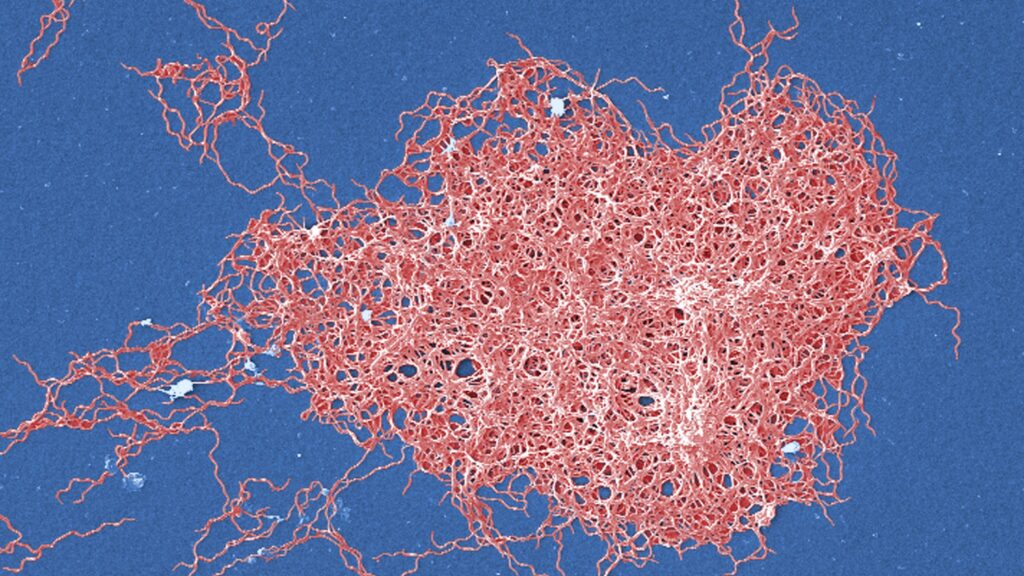

Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to people through the bites of blacklegged ticks. Those ticks are mainly found in the Northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and central Midwestern states, where most of the Lyme disease occurs.

People who are infected experience fever, headache, fatigue, and a skin rash that resembles a bullseye that develops around the site where the tick was attached. The infection is treated with antibiotics. But if left untreated, in some cases the infection can spread to the joints, the heart, and the nervous system, causing long-term problems.

Capturing the burden of Lyme disease is enormously challenging because existing diagnostic tests do not detect the disease in the first weeks after infection; they detect antibodies, which develop over time. Many people who are infected will have seen their doctors during that window where testing is ineffective and will have been diagnosed based on their symptoms and the tell-tale rash. And in many of these cases, doctors will not bother to order a blood test. In places where Lyme disease is common, doctors know what they are seeing.

“For the early stages of disease, it’s primarily a clinical diagnosis. It’s someone coming into their doctor … saying ‘Hey, I don’t feel well. Look at this rash on my leg. I was outside a couple of weeks ago.’ And they go: ‘Oh yeah, you’ve got Lyme disease,’” Kugeler said.

Insurance billing data suggest that about 476,000 people a year are diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease in this country. But the vast majority of these cases are never reported to public health authorities.

Some of those people probably didn’t have Lyme disease, Kugeler said, suggesting the true number of annual cases is likely somewhere between the insurance billing number and the number of cases where there was a laboratory test that triggered a report to public health.

The prior surveillance system required that public health departments check with every physician who ordered a test to see if the clinical picture supported a diagnosis of a current Lyme infection. The tests don’t easily distinguish whether antibodies are new — a sign of recent infection — or were developed in response to a previous Lyme infection. That’s where checking clinical information helps to weed out the true cases.

For states where Lyme cases number in the hundreds or thousands, that requirement had become unworkable, Kugeler said.

In 2020, Minnesota reported zero Lyme cases, not because there were no cases but “because their health department people who would ordinarily be following up on positive labs were all doing Covid work,” she said. In 2022, the state reported 2,685 cases.

In Massachusetts, where Lyme disease has been endemic for years, public health officials hit the wall even before the pandemic.

“The volume of suspect cases that needed to be investigated to get that clinical information was really overwhelming and was compromising the ability to do follow up on some other … diseases that also needed follow up,” State Epidemiologist Catherine Brown told STAT.

Massachusetts reported 5,052 cases in 2022, a 3,400% increase over the 144 cases it reported, on average, in the 2017-2019 period.

Brown, who is president-elect of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, said Massachusetts knew it wasn’t reporting a large number of its cases, because doctors either weren’t ordering tests, or were unwilling to spend time on the phone with public health department staff providing information on all of the Lyme cases they diagnosed.

“We knew Lyme was endemic [in Massachusetts]. We weren’t really learning anything new about it,” Brown said.

She was part of a group of state representatives that worked with the CDC to devise the new surveillance definition; she called the recognition that “have and have not” states had different needs in terms of Lyme surveillance “revolutionary.”

The change in the surveillance approach means comparing numbers from before and after 2022 won’t generate useful information; it’s an apples and oranges scenario. But the new system should provide a clearer picture of what is going on with Lyme disease going forward, Kugeler said.

Brown agreed. “For Lyme disease, surveillance has always been imperfect,” she said. “This continues to be imperfect, but it is a better, more sustainable way for states that have a high burden of this disease to be able to track trends in a way that also allows us to compare those trends across state borders.’’