- New criteria were proposed for a syndrome that mimics the clinical features of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Researchers called this disorder limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS).

- Unlike Alzheimer’s, LANS symptoms are restricted to memory loss and don’t involve other cognitive domains.

A new memory-loss syndrome that mimics the clinical features of Alzheimer’s disease was identified, researchers said.

“We propose a set of clinical criteria for a limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome [LANS] that is highly associated with limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy [LATE] but also other pathologic entities,” wrote David Jones, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and co-authors in Brain Communications.

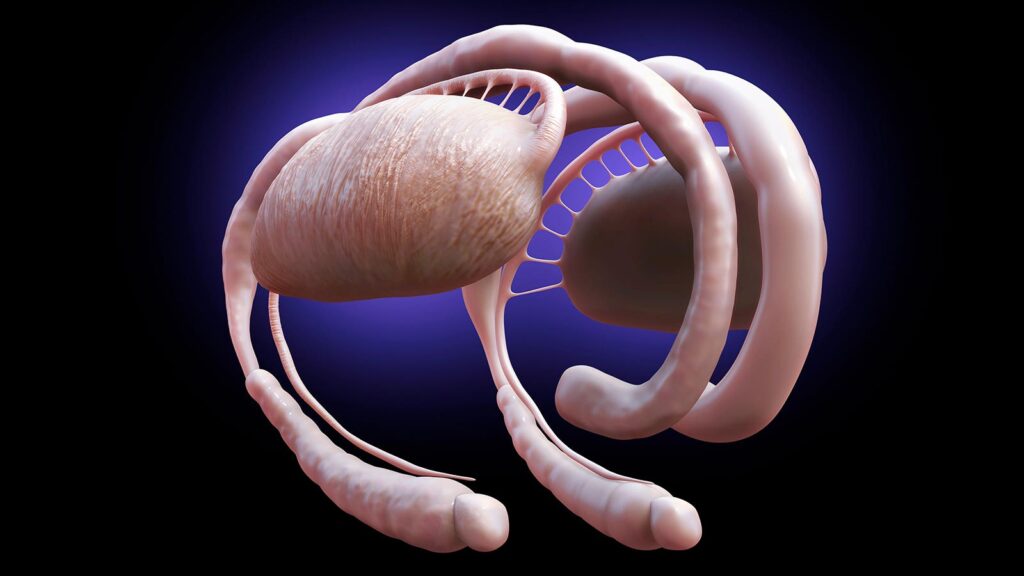

LATE — also known as LATE-NC (neuropathological change) — is a TDP-43 proteinopathy defined in 2019 based on autopsy findings and molecular characteristics of brain tissue.

“LANS and LATE are related, but not identical,” Jones said. “Most patients with LANS have LATE, but some patients with LANS may have Alzheimer’s disease or other causes of memory impairment,” he told MedPage Today.

“LANS can be diagnosed in living patients, while LATE can only be confirmed after death,” Jones noted.

Tau-negative neurodegenerative disorders like LANS can masquerade as Alzheimer’s dementia, but occur later in life. Unlike Alzheimer’s, LANS symptoms are restricted to memory loss and don’t involve other cognitive domains.

“In our clinical work, we see patients whose memory symptoms appear to mimic Alzheimer’s disease, but when you look at their brain imaging or biomarkers, it’s clear they don’t have Alzheimer’s,” Jones said.

“Until now, there has not been a specific medical diagnosis to point to, but now we can offer them some answers,” he added. “This research creates a precise framework that other medical professionals can use to care for their patients. It has major implications for treatment decisions, including amyloid-lowering drugs and new clinical trials, and counseling on prognosis, genetics, and other factors.”

The proposed criteria incorporate features like older age at evaluation (generally, age 75 and older), mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, the absence of neocortical degeneration, and a low likelihood of neocortical tau.

Jones and colleagues applied their criteria to 218 autopsied patients with an antemortem predominant amnestic syndrome in two cohorts — 165 patients from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center cohort and 53 from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort — who had Alzheimer’s neuropathological change, LATE-NC, or both pathologies at autopsy.

The neuropathology-defined groups accounted for 35%, 37%, and 4% of cases in the Mayo cohort, respectively, and 30%, 22%, and 9% of cases in the ADNI cohort. The criteria effectively categorized these cases, with Alzheimer’s disease having the lowest likelihoods of LANS, LATE having the highest likelihoods, and both pathologies having intermediate likelihoods. In the Mayo cohort, age at death for those with Alzheimer’s neuropathological change was 82.4 years; for those with LATE-NC, it was 91.6 years.

Patients with high likelihoods had a milder, slower clinical course and more severe temporo-limbic degeneration compared with those who had low likelihoods. Stratifying patients with both Alzheimer’s neuropathological change and LATE-NC from the Mayo cohort according to their likelihoods showed that those with higher likelihoods had more temporo-limbic degeneration and a slower rate of decline, while those with lower likelihoods had more lateral temporo-parietal degeneration and a faster rate of decline.

“It is important to reiterate that while LANS is highly associated with LATE-NC, it can be associated with other pathologic entities that selectively target the limbic system,” Jones and co-authors emphasized.

“One example that can be a potential source of clinical conundrums is the limbic variant Alzheimer’s disease, where tau predominantly localizes to the limbic system and therefore qualifies for LANS,” they pointed out. “In this scenario, the advanced LANS criteria in combination with visual assessment of tau-PET can help in determining which pathology has the highest likelihood of driving clinical symptoms.”

The low number of people with LATE-NC in the study is a limitation, the researchers acknowledged.

“Prospective studies are required to further assess the value of the LANS criteria in predicting underlying pathologies predominantly driving limbic versus neocortical degeneration,” they wrote. “This study is retrospective in nature. The implementation of the LANS criteria in clinical settings and prospective studies are needed to further validate and refine this set of criteria.”

-

Judy George covers neurology and neuroscience news for MedPage Today, writing about brain aging, Alzheimer’s, dementia, MS, rare diseases, epilepsy, autism, headache, stroke, Parkinson’s, ALS, concussion, CTE, sleep, pain, and more. Follow

Disclosures

The research was funded in part by the NIH, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Elsie and Marvin Dekelboum Family Foundation, the Liston Family Foundation, the Edson Family, the Gerald A. and Henrietta Rauenhorst Foundation, and the Foundation Dr. Corinne Schuler in Switzerland.

Jones reported no disclosures.

Co-authors reported relationships with the NIH, Bayer Schering Pharma, Piramal Life Sciences, Life Molecular Imaging, Eisai, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Merck, GE Healthcare, Siemens Molecular Imaging, the DIAN study, Biogen, Lilly Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Samus Therapeutics, Third Rock, Alzeca Biosciences, Alector, Cognition Therapeutics, EIP Pharma, Transposon, Genentech, and Nestle.

Primary Source

Brain Communications

Source Reference: Corriveau-Lecavalier N, et al “Clinical criteria for a limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome” Brain Commun 2024; DOI: 10.1093/braincomms/fcae183.

Please enable JavaScript to view the