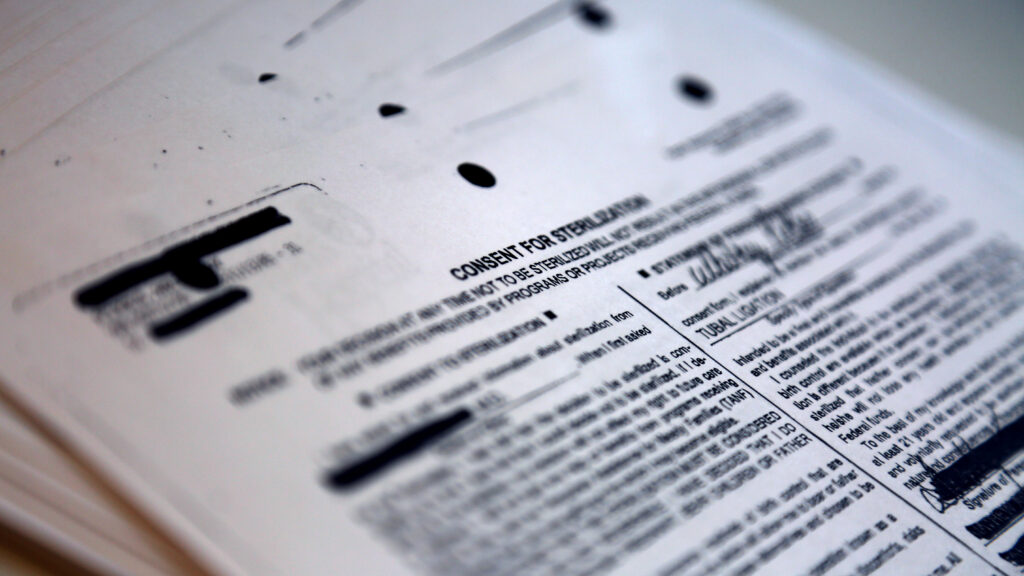

Often, women with sickle cell disease are told not to have kids. They might come to an appointment, happily pregnant, only for the doctor to tell them they shouldn’t be. They might be preparing for a scheduled C-section when their OB-GYN says that this pregnancy has gone smoothly but the next one could kill them. The illness is associated with an increased risk of serious pregnancy complications, which warrants a discussion — but sometimes that discussion can blur the line between advice and pressure. As a recent STAT investigation revealed, in extreme cases, some people have felt pushed into getting tubal ligations they didn’t want or fully understand.

Now, a data analysis commissioned by STAT shows that the rate of postpartum sterilization is significantly higher in Americans with sickle cell disease than in those without. Performed by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, the study found that between 2012 and 2019, 8.8% of deliveries to people with the condition ended in tubal sterilization, while 6.7% of births to unaffected mothers did.

advertisement

Zero in on certain parts of the country, and the contrast becomes more extreme. In Alabama, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Tennessee, for instance, the postpartum sterilization rate is 13.7% for those who have sickle cell and 8.1% for those who don’t.

Such gaps persisted even when researchers mathematically stripped away the effects of other variables that could be influencing the results, like age, income, insurance status, and whether the delivery was vaginal or cesarean.

These numbers can’t tell us why each sterilization took place. They can give us correlation, not causation. But just as variation in C-section rates among hospitals and regions has long prompted questions about equity and good practice, so does this analysis. Is tubal sterilization overused with certain kinds of patients in certain places? Or is it underused in others? To what extent do those patients have true autonomy? Would these patterns be different if there were more equal access to good care?

The data are derived from nearly 30 million deliveries included in a nationally representative dataset of inpatient stays, making the analysis the most comprehensive contemporary examination of sterilization rates in the American sickle cell community. It shows diagnoses logged and procedures performed, but billing codes don’t capture the emotional arc of a surgery. “Whether it was desired or not, what was happening behind the scenes, whether the physicians were properly giving them contraceptive counseling — that is something we can’t point out with this kind of data,” said Amy Luo, the Johns Hopkins Ph.D. student who did the statistical analysis and is the first author of the study.

advertisement

To some experts, though, the study adds weight to the accounts of women with sickle cell who’ve been discouraged from having kids or felt coerced into getting tubal ligations.

“Sometimes people will look at an article in a newspaper and say, ‘Oh well, that’s just a few women’s stories,’” said Kim Mutcherson, a bioethicist and professor of law at Rutgers University, who wasn’t involved in the research. “When you look at these discrepancies, it’s much harder to claim, ‘Oh, that’s just a few folks who have bad doctors.’ You have to start thinking, what are the systemic reasons why we are seeing these kinds of disparities?”

The question isn’t entirely new. For decades, researchers have wondered why sterilization rates varied from region to region, from group to group. Women were more likely to have their fallopian tubes severed or removed if they were low-income. Same thing if they were Native American, Latina, or Black. Same thing if they lived in the South. There were outliers and exceptions, but these numbers came with troubling possibilities. “You get worried,” said Nikki Zite, an OB-GYN at the University of Tennessee. “Is there poor counseling? Is this still some remnant of all that reproductive coercion?”

By “all that reproductive coercion,” she’s referring to the tens of thousands of women forcibly sterilized in the U.S. in the 20th century. Often, they were poor, and people of color; some were living with a disability. Sometimes, surgeries were ordered by state eugenics boards — government institutions charged with curbing the reproduction of the “unfit.” Sometimes, they were consented to under duress, with doctors pushing sterilization while someone was in labor or woozy with painkillers, falsely claiming that the surgery was easily reversible, or saying, “If you don’t get this, you’ll die.” Sometimes, they were simply performed without the patient’s permission when she came in for a different procedure — what became known as “Mississippi appendectomies.”

While the overt practice largely came to an end in the 1970s, subtler versions have persisted: sterilizations in prisons without proper approvals, patients feeling like they can’t say no. Given all of that, the continuing variation in tubal ligation rates conjures the specter of surgeries not fully consented to. Then again, there are plenty of people who actively want these procedures, many of whom have to fight to get them. Coercion is hardly the only explanation for variance. The contraceptive method you choose, for instance, is shaped by the choices of those around you, making it more likely for you to seek a tubal ligation if that’s what you’ve heard about from your mother or sister or friends.

The new analysis adds yet another question into the mix. Sickle cell disease is a perfect storm of confounding factors, as far as sterilization goes. The vast majority of Americans who have the disease are Black — historically, one predictor of tubal ligation. About two-thirds of them are on government insurance — another predictor. More than half of them live in the South — yet another predictor.

“That’s the central question,” said Lydia Pecker, the lead author of the study and interim director of the Johns Hopkins sickle cell center for adults. “Is this a phenomenon that mirrors what larger populations experience, or is there a sickle-specific dynamic?”

There are hints that something specific is, in fact, going on. When Pecker’s team analyzed data only from Black patients, for instance, those with sickle cell still had higher odds of getting a postpartum tubal sterilization than those without. Likewise, having pregnancy complications increased a patient’s odds of having this surgery across the board — but the increase was significantly bigger for those with the disease.

In other words, when you adjust for other factors between the sickle cell and non-sickle cell groups, making all else equal in terms of geography, age, income, and insurance status, those with both the illness and pregnancy complications have twice the probability of getting a sterilization as those who have pregnancy complications but not the illness. The raw, unadjusted percentages reflect that trend. Among sickle cell patients who had severe pregnancy complications, 16.7% got postpartum sterilizations; among patients without sickle cell who experienced the same issues, 8.6% got those surgeries.

It’s possible that among the crises that count as severe complications — heart issues, respiratory problems, cases of sepsis — the ones affecting people with sickle cell might be more severe on average, which might nudge them towards permanent contraception. Or the experience of those complications is different for people who’ve had a lifetime’s worth of health troubles, making them warier of getting pregnant again. Or it could be that doctors are more vociferous in recommending sterilization for those with sickle cell.

Different explanations may be true in different cases. They might be simultaneously true for one person, with various voices and forces tugging and twisting in their mind.

It’s impossible to talk about sickle cell without talking about racism. The debilitating pain it brings has long been a metaphor for the systemic suffering of Black Americans that white Americans are quick to dismiss. There’s a kind of double-think in the way patients get treated. Show up to an emergency room in the agony of a sickle cell crisis, and you might be disbelieved and brushed off as drug-seeking. Die in police custody, handcuffed and gasping, as the New York Times reported in 2021, and sickle cell might be invoked as an excuse.

That inequality exists in the very structure of the medical system. Often, to elucidate it, researchers use cystic fibrosis as a comparison, because it, too, is a debilitating genetic illness affecting tens of thousands of Americans, but the majority who have it identify as white. For instance, there are around 100,000 patients with sickle cell disease in the U.S. — over three times as many as the estimated 30,000 with cystic fibrosis — but significantly more research funds have gone to cystic fibrosis than to sickle cell. In 2021, there were 280 nationally recognized cystic fibrosis treatment centers and only 30 for sickle cell.

The new study makes that comparison, too. Among deliveries to women with cystic fibrosis, 6.6% ended with tubal sterilization — almost the same as in the overall population, and significantly fewer than the 8.8% in the sickle cell group — although that statistically notable difference melted away when Luo adjusted for other variables like insurance status.

Although cystic fibrosis comes with an increased risk of pregnancy complications — smaller than the one associated with sickle cell, but greater than the general population’s — the odds of tubal sterilization did not go up for cystic fibrosis patients who experienced them. In other words, it doesn’t seem to be that just having a maternal-complication-prone genetic illness increases the chances of getting sterilized. It seems like there’s something more particular going on.

To some, it’s hard not to see discrimination in such discrepancies — be it racism or sickle cell-related stigma, or some combination of the two. “This puts real numbers behind what I think all of us who have cared for patients living with sickle cell disease have known for a long time: that there are key differences in the way that our patients get treated,” said Sharl Azar, medical director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Center. “Patients with sickle cell disease are treated like second-class citizens.”

Kavita Arora, an OB-GYN at the University of North Carolina, points out that family planning decisions are complex. It can be hard to tease apart how much variation is due to patient preference, how much to physician or structural bias. There are real barriers for some people who want tubal ligations. If certain variations are due to true patient choice, she said, “it’s important to celebrate that people are getting the kind of contraception that they desire.” But if those differences are due to outside pressures, that’s concerning — and this study, while preliminary, does signal some cause for concern, she said.

There’s also a murky middle ground. Bodily autonomy is hard to separate from access to care. As Luo put it, “Maybe people are choosing to undergo this procedure because they’re unsure about their future insurance coverage, for, say, birth control pills or getting their IUD replaced.” That isn’t coercion, in the classic sense, but it isn’t free choice, either. The same might be said for practice differences between hospitals or regions. If the doctor that you’re able to see has been slower to adopt some contraceptive methods, there might not be overt personal pressure, but there’s a systemic force pushing you toward a permanent surgery that you might not have gotten if more possibilities were on the table.

Likewise, the inability to get specialized care might influence the decision about sterilization. The combined risks of sickle cell and pregnancy can be mitigated if maternal-fetal medicine doctors and hematologists team up to provide care, offering treatments such as blood transfusions and blood thinners. But that isn’t accessible to all patients. In some parts of the country, even basic obstetric care is a long drive away — and many general physicians may not be aware of the research on best practices for managing these pregnancies.

“We know that pregnancy is one of the most vulnerable periods in the lifespan of a woman with sickle cell disease. It certainly isn’t without risk,” said Deva Sharma, a hematologist and transfusion medicine specialist at Vanderbilt. “But rather than telling patients, ‘don’t become pregnant,’ why not implement the highest level of evidence to reduce their risk?”

In many ways, this study is a tantalizing glimpse. It has not been peer-reviewed, and has so far only been published on MedRxiv, a preprint server. It begs further research. It isn’t a smoking gun that reveals rampant coercion. Nor is it a reassurance that such stories are few and far between.

There is, after all, no “correct” rate of permanent contraception. Compared with C-sections, said Sarah Little, an OB-GYN at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, “it’s more elective” — one method among many. What makes it right is that it’s what the patient truly wants, after being truly informed.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of reproductive health care supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.