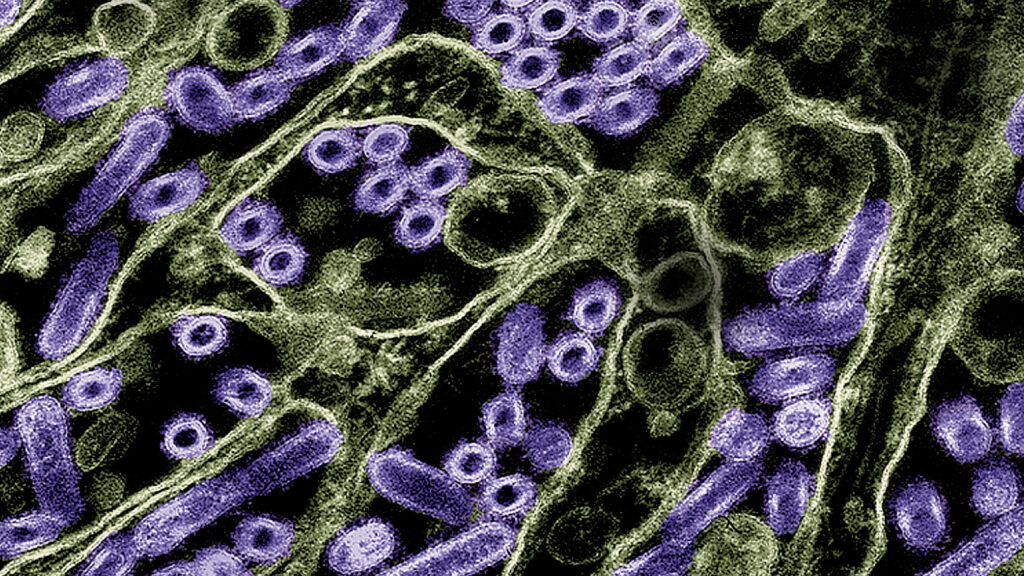

A study published Monday provides new evidence that the H5N1 virus currently causing an outbreak of bird flu in U.S. dairy cattle may be adapted to better infecting humans than other circulating strains of the virus, a result that is already courting controversy among the world’s leading flu researchers.

Across the globe, different influenza viruses are constantly circulating in many different kinds of animals. One of the things that determines what kind of animal a given flu virus can infect is the type of receptors present on the outside of tissues that virus comes in contact with. Flu viruses that typically infect birds have an affinity for latching on to the particular shape of a receptor commonly found in the guts of avian species. Human influenza viruses, on the other hand, prefer the shape of a receptor that lines our upper respiratory tracts.

advertisement

The new work, published in Nature, showed that the bovine H5N1 virus could bind to both receptors.

“There is an ability to bind to human-type receptors,” the study’s lead author, Yoshihiro Kawaoka, told STAT in an interview. But he cautioned that it’s too soon to say whether this ability means the recently emerged bovine branch of the H5N1 evolutionary tree has increased potential to become a significant human pathogen. “Binding to human-type receptors is not the only factor that is required for an avian flu virus to replicate well in humans,” said Kawaoka, a leading influenza virologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has studied H5N1 for decades.

The work on predicted binding offers new evidence for wider attachment, including to cells lining the human upper respiratory tract but requires further study to understand the underlying factors, Ian Brown, the former virology head at the U.K.’s Animal and Plant Health Agency who is now a group leader at the Pirbright Institute, said in a statement to reporters. “Overall the study findings are not unexpected but this report provides further science insight to an evolving situation, that emphasizes the need for strong monitoring and surveillance in affected or exposed populations, both animals and humans to track future risk.”

advertisement

The result is sure to stoke fears that the H5N1 virus now circulating in dairy cows has already adapted toward spreading more efficiently in humans. But complicating this picture is the fact that other scientists, who have examined these same molecules that the bovine H5N1 virus uses to infect cells, have gotten different results.

James Paulson, the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Chair of Chemistry in the Department of Molecular Medicine at the Scripps Research Institute, told STAT via email that his lab, in collaboration with two different research groups, has found “no suggestion that there is increased ‘human type’ specificity” in the H5N1 virus now expanding across U.S. dairy herds.

Scott Hensley, a professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania, whose group is one of the ones working with Paulson, said in an email that their data suggest the bovine H5 molecule binds poorly to human receptors. “It will be important for us to determine why we are seeing different results,” he said.

Kawaoka acknowledged the conflicting data — which are not yet published — and attributed the disagreement to differences in experimental design. His own team used a method that involves coating plastic plates with microscopic forests of synthetic versions of the different receptor subunits, mixing them with H5N1 virus, and then measuring how much virus sticks.

It’s the same method his group used more than a decade ago, to show that an H5N1 virus his lab had successfully (and controversially) altered to be transmittable through the air among ferrets had gained the ability to bind to human-type receptors. “So there’s an association of this ferret transmissibility and binding to the molecule that we’re using,” Kawaoka said.

The other groups used not just the sub-units, but the whole receptor molecule that naturally exists on human cells.

Ron Fouchier, a flu virologist at Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands who was not involved in either study, told STAT via email that the UW-Madison team’s method is easy to perform and interpret, but that there are other available methods that would result in a clearer picture of binding specificity.

“The dual receptor binding is interesting, but I do not find these [results] very unsettling,” Fouchier wrote. “This is an interesting initial observation that requires more work.” In particular, he’d like to see analyses that probe which mutations are driving the virus’s ability to bind to different receptors.

Other components of the study added to existing evidence that the H5N1 virus is not very good at infecting mammals through the respiratory route, but that it has an affinity for mammary tissue and can transmit efficiently through contaminated milk.

Previously, a team led by Kawaoka had shown that female lab mice that were fed milk from H5N1-infected cows became very ill, and that the virus spread throughout their bodies, including into their mammary tissue, teats, and brains. In this latest research, the scientists repeated those experiments with smaller doses of infected milk, confirming that mice are susceptible to infection from consuming even tiny amounts — less than a single drop of milk.

They also showed for the first time that vertical transmission is possible; female mice infected with the virus could pass it on to their pups through their own milk.

Another aspect of the study involved intranasally infecting ferrets, which is commonly used to study transmission through the air of respiratory viruses. The experimentally infected animals fell ill with fever and lost weight, but they did not efficiently spread the virus to other ferrets housed in cages close by. None of the four exposed animals developed clinical signs of disease or produced detectable levels of virus in their nasal passages, although one did develop some influenza antibodies — suggesting there is some potential of spreading between ferrets via the respiratory route, but that it does not happen easily.

These data are consistent with another study conducted by researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in May. It found that an H5N1 virus isolated from the first human case tied to the dairy cow outbreak — a farmworker in Texas — spread easily between ferrets sharing the same cage, but not between cages where the animals shared air but had no direct contact. In that situation, only one out of three exposed animals became infected.

“It’s not zero transmission; there is some transmission but it’s very limited,” Kawaoka said. That should provide some reassurance that the virus has not yet acquired the ability to easily spread through the air. But how long that will stay true, with the virus expanding its footprint — and with it, opportunities to adapt to human biology — is anybody’s guess.

“Continued surveillance is needed,” Kawaoka said. “We need to be concerned.”

Helen Branswell contributed reporting.