Ufere is a transplant hepatologist.

Few Americans, including some healthcare professionals, realize that chronic liver disease is now the 9th leading cause of death in the U.S. Even worse, it is the 5th leading cause of death among adults ages 25 to 64 years old.

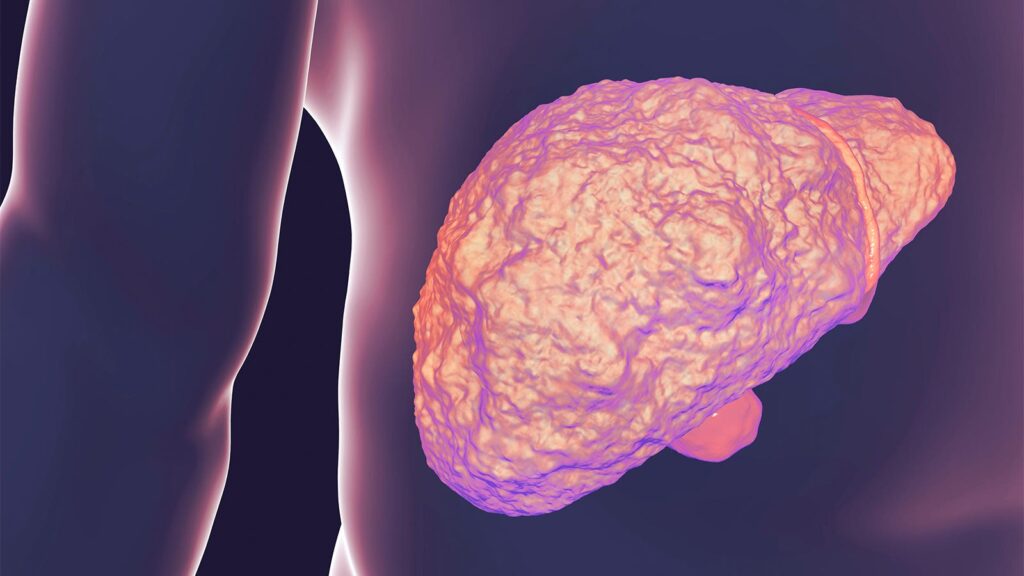

As a transplant hepatologist, I specialize in the care of people living with chronic liver disease, which affects 4.5 million Americans, or nearly 2% of the adult population. Some people with chronic liver disease can go on to develop cirrhosis, which often leads to liver failure. Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis disproportionately affect Americans who are medically and socially disadvantaged, especially those living in rural areas. In contrast to other chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease and some types of cancer, which have had decreasing mortality rates in the U.S. over the past 2 decades, mortality from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis have sharply increased.

Why Is This Happening?

We know that increasing rates of harmful alcohol use over the past 2 decades have led to skyrocketing rates of alcohol-associated liver disease. From 2001 to 2013, there was a 30% increase in high-risk drinking (defined as having four or more drinks on any day at least once weekly for women, or five or more for men). Excessive alcohol consumption worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, with nearly 1 in 4 adults reporting drinking more to cope with pandemic stress in a survey conducted by the American Psychological Association. This has led to skyrocketing rates of alcohol-associated cirrhosis, which is now the leading cause of liver transplantation nationally.

Unfortunately, many people with alcohol-associated liver disease are diagnosed too late. The scary reality of liver disease is that it is insidious: the majority of people with cirrhosis can be completely asymptomatic for several years, even decades. But with ongoing injury to the liver from alcohol use, some people can suddenly develop signs of liver failure. These signs can include jaundice, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal hemorrhage. Once people with alcohol-associated cirrhosis develop any of these signs of liver failure, they are often facing the need for a liver transplant. But some are diagnosed so late that they are too sick to safely undergo a liver transplant, often leading to their death.

How Do We Address the Crisis of Alcohol-Associated Cirrhosis?

First, we must dedicate ourselves to reducing the use of stigmatizing terminology. As a transplant hepatologist, I have too frequently observed how social stigma associated with alcohol use directly contributes to delayed diagnoses. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, along with three other international liver societies, released a joint statement calling for the end of stigmatizing language in alcohol and liver disease. Changing our terminology to replace the term “alcoholic” with “alcohol-associated” or “alcohol-related” cirrhosis in lay media, medical literature, and clinical care is an important, and easy, first step to improve the delivery of non-stigmatizing care.

Second, we need to increase public awareness of cirrhosis, particularly alcohol-associated cirrhosis, as a disease of despair causing premature death in the U.S. In 2021, over 56,000 Americans died from cirrhosis. That’s more than died from suicide, another disease of despair, in the same year. Sadly, cirrhosis receives disproportionately less public health attention.

Non-profit organizations such as the American Liver Foundation have core missions to promote awareness and education about liver health across all 50 states through national public health campaigns. Depending on your specialty, you may have an opportunity to bring this up during patient visits or to get involved with national or local campaigns.

Lastly, stricter alcohol policies and legislation hold the most promise for reducing alcohol consumption and alcohol-attributable harms at a national level. Researchers from the University of Michigan and Boston University found that more restrictive alcohol regulations were associated with lower alcohol-associated liver disease mortality across the U.S. This was also observed in Scotland, where the implementation of minimal unit pricing legislation for alcohol was associated with a 13.5% reduction in deaths attributable to alcohol consumption between 2018 and 2020. Based on the success of this legislation, the minimum price of alcohol in Scotland is set to increase by 30% this May.

Is it time for the U.S. to consider the same to save American lives?

Nneka N. Ufere, MD, MSCE, is a transplant hepatologist and assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and Harvard Medical School, and a public voices fellow of the OpEd Project and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Please enable JavaScript to view the