Panosian Dunavan is an infectious diseases expert.

Author’s note: In this column, “leprosy” and “Hansen’s disease” are used interchangeably. “Leper” — a highly stigmatizing term — should not be used to refer to an infected person.

Earlier this month, a report in Emerging Infectious Diseases prompted a flurry of internet headlines plus some outlandish theories. COVID vaccines causing leprosy? Seriously?

Nonetheless, the data themselves were notable. Although the overall count of newly diagnosed Hansen’s disease in the U.S. — roughly 150 to 200 cases per year — hasn’t changed in several decades, the percentage found in southeastern states has risen over time. In 2020, an astounding one in five infections in the U.S. were diagnosed in central Florida, and 34% were locally acquired.

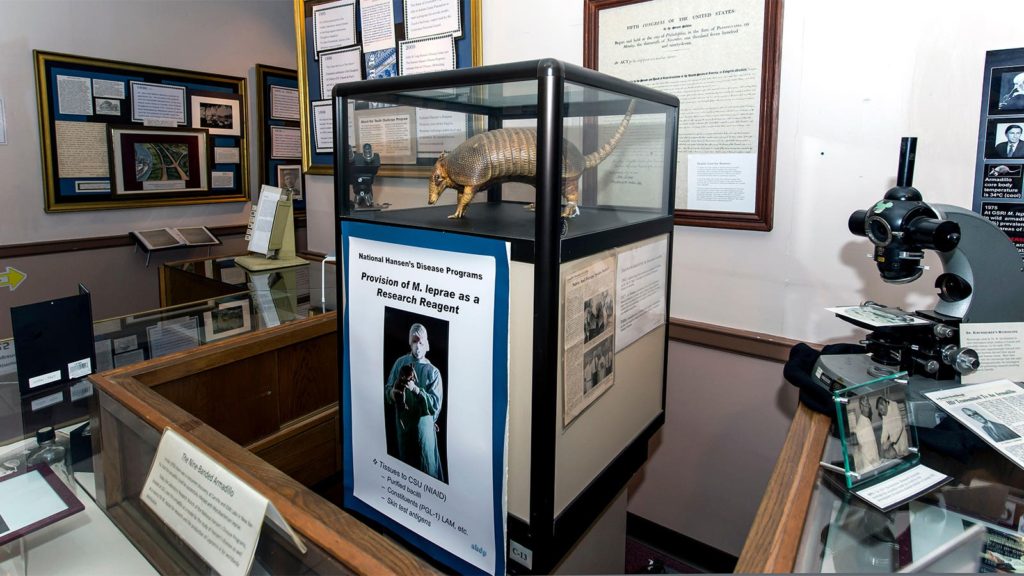

Is Florida an emerging hotspot on the leprosy map? I believe the answer is yes. For one thing, Florida has plenty of nine-banded armadillos, a known animal reservoir of Mycobacterium leprae in certain parts of the Americas. But before focusing on this possible source of transmission, let’s step back.

Although leprosy remains a neglected infectious disease that sometimes causes tragic, lifelong disability, its global incidence has dramatically fallen since the mid-1980s. Much of this drop reflects newer multi-drug treatments. Nonetheless, transmission still occurs unabated in highly endemic countries. Ignorance and fear surrounding leprosy also persist in many parts of the world, countering efforts both to identify and treat what some might argue is one of the world’s least contagious infections.

A Lingering Legacy of Stigma and Pain

Most people know that leprosy has long caused stigma and exclusion. What many do not know is that its worst persecution dates from medieval times, likely reflecting both fear and strict adherence to the biblical injunction (Leviticus 13:46) that the “unclean” should “dwell beyond the camp.” By 1225, the number of segregated hospitals in Europe for purported sufferers peaked at 19,000. Then the numbers fell for reasons no one truly understands.

Today, leprosy can still trigger cruel reactions. For example, affected women living in highly endemic countries sometimes suffer ghettoization and complete exclusion from normal household life. Some also fear separation from their children.

Clinical Leprosy Up Close and Personal

Dateline: Carville, Louisiana, 1978. After flying to New Orleans, then boarding a bus, I finally arrive at an isolated, antebellum compound on the eastern edge of the Mississippi River. My goal? To attend a week-long course at the then-named “National Leprosarium.” It was at Carville that I first saw the heartbreaking harm M. leprae sometimes inflicts. But it was also there I met inspiring researchers, staff, and, most of all, leprosy patients with resilience and hope.

After visiting Carville, I continued to see patients here and abroad with every form of leprosy, from early rashes to end-stage (and preventable) sequelae including blindness, ravaged faces, missing digits, and palsied limbs. My most recent experience? At a county hospital clinic in Los Angeles that currently follows more than 250 patients.

Not surprisingly, immigrants comprise the vast majority of clientele at L.A. General Medical Center. Some were born in the Indian subcontinent, Brazil, the Philippines, or certain Pacific islands, while others are natives of Mexico or Central America. Still others are lifelong U.S. citizens who served in the Vietnam War. And yes, the L.A. County Hansen’s clinic also sees patients who have never left the U.S. but have previously resided in states with infected armadillos.

The director of the Hansen’s clinic is Maria Teresa Ochoa, MD, a tropical dermatologist who was born in Colombia. Ochoa first saw patients with leprosy while providing medical care to indigenous people in the Amazon and observing the same ostracism and shame that has dogged leprosy through the ages.

“I’m very compassionate about that,” says Ochoa. “How can an infection you can now treat with antibiotics change the course of your life for 20 or 30 years? Or cause you to live with a secret you cannot share with anyone — even your own family?”

Ochoa believes we can do better.

Diagnosis and Treatment

American doctors’ biggest problem in managing leprosy is failing to recognize it early, which can help avert long-term complications. To avoid pitfalls, here’s a basic primer:

- Never forget that M. leprae is an infection that affects skin and peripheral nerves, and whose clinical incubation can be incredibly long, ranging from several years to many decades.

- An early Hansen’s disease skin lesion can be a macule, papule, or nodule, sometimes anesthetic, sometimes not. A far smaller percentage of patients present with no skin manifestations, only unexplained inflammation of an affected nerve or peripheral paresthesias, even uveitis.

- Diagnosing leprosy typically requires histopathology and a Fite stain of a full-thickness skin biopsy. A patient’s Fite stain will often reveal red-staining bacilli. PCR tests can also detect the infection in biopsied tissues.

- There are five subtypes of leprosy that correlate with an individual patient’s clinical features and density of bacilli on biopsy. Every patient should be classified according to their subtype (tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous) as defined by the classic Ridley-Jopling scale.

- All patients with active M. leprae infection should receive at least two antibiotics. Sudden immunologic reactions can occur either on or off treatment, at times requiring rapid initiation of high-dose corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents to prevent permanent nerve damage and long-term disability.

- Clinical assistance and referrals to specialized clinics in 12 states are available through the U.S. National Hansen’s Disease Program in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Putting Florida’s Cases in Context

Can people contract leprosy right here in the U.S.? Based on the latest Florida data: yes. But this is hardly news to leprosy experts. From 2005 through 2014, 65% of 96 leprosy cases reported in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida were in people who were both born in the U.S. and had never left the country. Moreover, all of these states harbor M. leprae-infected armadillos.

Although most cases of leprosy in heavily endemic areas probably result from respiratory droplets and prolonged person-to-person contact, the disease’s zoonotic transmission remains poorly understood. In some cultures, people hunt and eat armadillos, which suggests another route of exposure. We also don’t know if M. leprae in the Americas might have an environmental reservoir in soil or animal droppings.

In a recent letter in the New England Journal of Medicine, Ochoa and colleagues described six newly diagnosed American patients with leprosy who had no obvious risk factors. Did they long ago travel to an endemic area, she wonders, and acquire infections that lay dormant for decades until mild immuno-senescence finally allowed them to flower?

To answer that question, she says, we still need more research.

Panosian and Ochoa continue their discussion about Leprosy here.

Claire Panosian Dunavan, MD, is a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a past-president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. You can read more of her writing in the “Of Parasites and Plagues” column.

Please enable JavaScript to view the