Hotez is a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology.

It might not be intuitive why, as an MD-PhD laboratory investigator who develops vaccines for global health, I should also take on the challenge of combating anti-science or authoritarian regimes. Some colleagues, especially those who have been scientists for decades, even question my taking a public stance. Their position is a traditional one, that countering anti-vaccine movements or defending science and scientists is best left to others, while speaking out to defend the discipline is even inappropriate for our profession.

But I believe that confronting anti-science movements is essential and necessary. Our training as biomedical scientists gives us the knowledge and tools to advance the fields of biochemistry and molecular biology, microbiology, neuroscience, pharmacology, and physiology. Many of us even apply our training to develop novel and exciting technologies, such as new medicines, diagnostics, medical devices, or vaccines. A common denominator is that we use science to save lives. I embarked on MD-PhD training to apply the then-new science of molecular biology — the first gene had been cloned just a few years earlier — to the study of medically important parasites in Africa and elsewhere. I brought hookworms into the Rockefeller University Laboratory of Medical Biochemistry (headed by Anthony Cerami, PhD) to take a first stab at developing hookworm vaccines. Now we have a human hookworm vaccine in clinical trials in Africa, as well as a vaccine for another devastating parasitic infection known as schistosomiasis, and of course our COVID-19 vaccine released for emergency use in India.

It is in that same spirit that I embarked on a parallel career of combating anti-science. My mindset for writing and publishing the book about my daughter, Rachel, was basically: If I don’t write this or stand up for vaccines, then who will? After all, I am a vaccine scientist and have particular expertise on information that conclusively shows there is no vaccine-autism link. I also have firsthand knowledge about autism; I discussed with Rachel’s medical geneticists the steps of whole exome sequencing to identify her autism gene. A downside to writing about Rachel was that it invited waves of attacks from the anti-vaccine movement. However, this also gave me experience and understanding about the tactics and approaches used by these groups. By circumstance, I became an anti-science expert.

On my early CNN and MSNBC appearances in 2020, I was among the first to call out the Trump West Wing for its use of disinformation and anti-science propaganda — not from brilliance, but because by default I had become a national expert in deciphering the rhetoric of anti-science, including the false narratives in particular, which in some cases are spun around real facts. Beginning in 2021 and continuing into 2022, with 200,000 unvaccinated Americans needlessly losing their lives because of their COVID-19 vaccine defiance and refusal, I again felt an obligation to confront and combat this anti-science aggression.

Those of us in the biomedical community who feel it is a moral imperative to direct our scientific energies toward saving lives must recognize that battling anti-science is an essential element of this cause. For inspiration, I turn to the writings and thoughts of Jacob Bronowski (1908-1974). Bronowski was a Polish-born mathematician and philosopher who taught mathematics in the U.K., and over time became a renowned public intellectual through his writings, and later as the presenter of a BBC documentary (and companion book) known as The Ascent of Man. One of the more moving segments was filmed at Auschwitz as Bronowski spoke about a dark side of science that can be twisted for nefarious purposes. Previously, in his 1956 book, Science and Human Values, Bronowski wrote about the liberation of the concentration camps and Holocaust victims, as well as the aftermath of the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He used these examples to develop an essential moral framework for scientists. Bronowski became one of the first “scientific humanists” in residence after the founding of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. When I met with Jonas Salk, MD, there in 1995, he explained to me that the rationale during the organization’s early years for devoting a part of the institute to building bridges between the sciences and the humanities was the striking gap between the two groups. He and Bronowski believed that close intellectual contact between each discipline could significantly enrich the other. Over time, for the institute to focus on its continued excellence in biomedical sciences, this emphasis on the humanities became a lesser priority.

Therefore, it remains urgent to build out meaningful programs in the humanities and public engagement at many of our major research institutions and universities. There are now some interesting and successful examples of such collaborations, including the Center for Humanities & History of Modern Biology at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, strong programs in the humanities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a 2018 report from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on integrating humanities and the arts into science, medicine, and engineering. However, much more needs to be done.

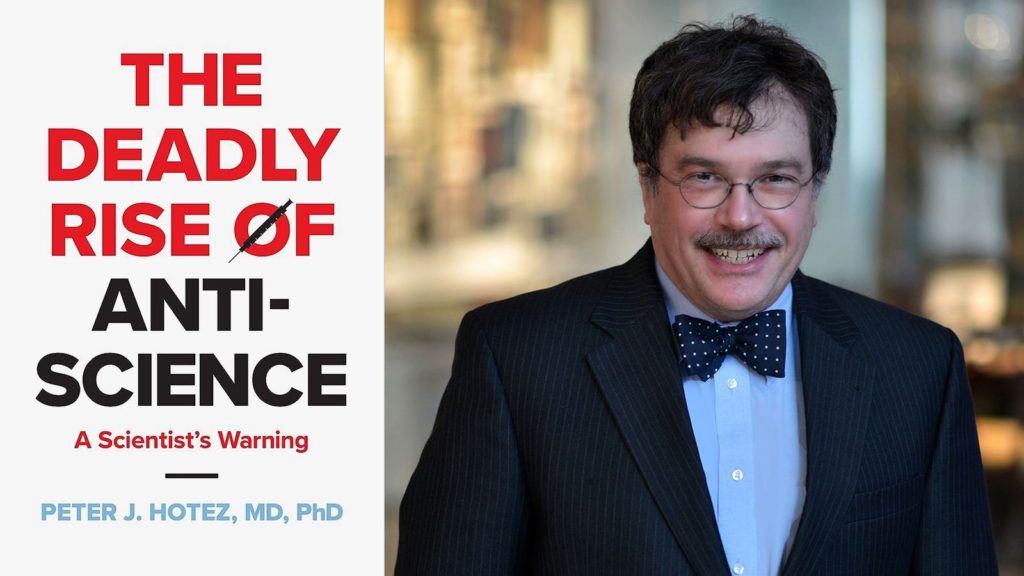

Peter J. Hotez, MD, PhD, is a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology, and the founding dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, where he is also the co-director of the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development. This piece was excerpted from his new book, The Deadly Rise of Anti-Science: A Scientist’s Warning. Copyright 2023. Published with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

Please enable JavaScript to view the