Want to stay on top of health news? Sign up to get our Morning Rounds newsletter in your inbox.

Good morning! Amid today’s news, two items on pregnancy that are interesting and eerie to read in tandem. And on top of that, two itchy pieces of mosquito-related news from STAT’s Helen Branswell.

advertisement

Health Care’s Colossus: UnitedHealth promised it would be hands off. It wasn’t.

Take our money, the company said. We’ll handle the business side while you look after your patients, it said. Together we can create a future where primary care leads, it said. Those were the promises UnitedHealth Group made in 2014 to ProHealth Physicians, a reputable Connecticut-based primary care network with more than 50 clinics across the state.

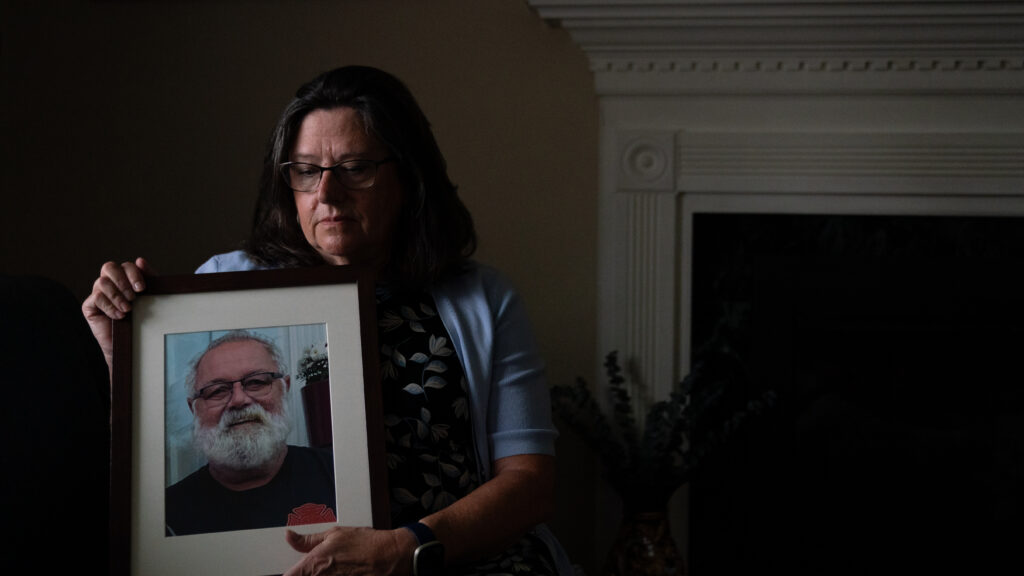

But doctors say the promises weren’t kept — 10 years later, the group is a shell of its former self. “People cannot get the care that they need,” said Sharon Maloney, whose husband couldn’t get into his doctor’s office for three days, precipitating a chain of events that led to his death.

In Part 3 of STAT’s investigative series on UnitedHealth Group’s physician empire, reporters recount in detail how the story unfolded at ProHealth. My colleagues spoke with more than 15 former doctors, current and former patients, and experts. They also obtained documents through public records requests.

advertisement

Read the story. And if you haven’t already, go back to read Part 1 and Part 2.

CDC announces $118.5 million to investigate maternal deaths

The Biden administration announced yesterday that CDC will invest $118.5 million over five years to help identify and prevent pregnancy-related deaths. Specifically, the funds will go toward expanding a system of Maternal Mortality Review Committees from representing 46 to 52 states and U.S. territories. The groups review deaths within each state or territory that occur within one year of the end of a pregnancy to determine if the deaths were preventable, and recommend how the deaths could be prevented in the future. Funds will also be used to implement the White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, according to the announcement.

Maternal mortality is tricky to measure, but by all expert accounts, the U.S. is in the midst of a crisis. It’s yet to be seen how additional funding from the federal government will affect the work done by MMRCs. “Increasingly, the reporting of those findings have become a political issue, and there have been efforts to suppress their findings,” researcher Greg Roth told STAT’s Nalis Merelli last summer. Between 2017 and 2019, only 36 state groups reported their findings to the CDC.

Can you imagine having your tubes tied then getting pregnant anyway?

It happens — to about 3 to 5% of people who receive tubal sterilization, according to new estimates published yesterday in NEJM Evidence. Researchers used data from the National Survey of Family Growth collected in waves over the last two decades. Among women surveyed between 2013 and 2015, the researchers estimated that about 2.9% of those who had their tubes tied became pregnant within a year. But an estimated 8.4% had become pregnant within 10 years of the procedure.

The results indicate “nontrivial” rates of pregnancy after the purportedly permanent procedure, the authors write. It’s good to know, as data from the same survey show that about a third of women receive the surgery by the age of 44.

What is Oropouche virus, should I be worried about it, and how do I pronounce it?

Twenty-one people in the U.S. have contracted the Oropouche virus during travels to Cuba over the summer, the CDC reported yesterday. The island country is experiencing its first ever recorded outbreak of the virus, which has also been spreading in several South American countries. But what exactly is Oropouche virus?

As usual, STAT’s Helen Branswell has us covered. The virus is spread through biting insects — specifically one species of midge, which is a small fly, and one type of mosquito. About 60% of people who become infected will develop symptoms like fever, severe headache, chills, muscle aches, and joint pains. And there isn’t a vaccine or specific drug treatment for the virus, so the best way to avoid it, as Helen writes, is to not get bit.

Read more on everything you need to know about the virus including how to pronounce its name.

Rare mosquito-borne encephalitis is found in four states, with one death

In more mosquito news: New Hampshire has recorded the country’s first death this year from eastern equine encephalitis, a rare but dangerous disease spread through the bite of infected mosquitoes. The CDC says it has been informed of four human infections so far in 2024, with Wisconsin, Massachusetts, and New Jersey also reporting cases. All four involve neuroinvasive disease, meaning the virus moved into the brain. About 30% of Triple E cases are fatal, and survivors often have long-term neurological problems. Massachusetts has begun spraying mosquitoes in some communities, and is urging people to consider remaining indoors from dusk to dawn to avoid being bitten.

Triple E infections typically occur in late summer and early fall, before cool temperatures kill off the mosquitoes that spread it. The virus is most commonly found along the Gulf Coast, in the Atlantic states and around the Great Lakes. The number of cases varies by year, though most years fewer than 10 cases are reported. In 2019, however, a record 38 cases were reported.

—Helen Branswell

NIH empowers Native Americans to study substance use in their own communities

The National Institutes of Health has announced plans to devote over a quarter-billion dollars to researching substance use and drug overdose among indigenous tribes across the country. But there’s a community-driven twist: Tribes and tribal-serving organizations get to design and conduct the research themselves.

Of course, major initiatives promising to serve indigenous people can be tricky to execute, given the federal government’s track record of violence and broken promises — and broader mistrust of research projects aimed at historically marginalized communities, STAT’s Lev Facher reports.

But that context is the “foundation of this program,” said Kathy Etz, the director of Native American Programs at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Tribes want to lead research, they want to be directly funded to lead research, and they want the research to reflect the priorities of their communities,” she said. “What we’re doing here is supporting tribes and Native American-serving organizations to do what they want.” Read more from Lev.

What we’re reading

-

What mental health care protections exist in your state? Pro Publica

-

America is doubling down on sewer surveillance, The Atlantic

- Medicare’s new transitional coverage of emerging technologies program doesn’t go far enough, STAT

- Polio vaccines arrive in Gaza, but distributing them is the next challenge, New York Times

- Exclusive: Centene eliminates brokers’ commissions for Medicare drug plans, STAT