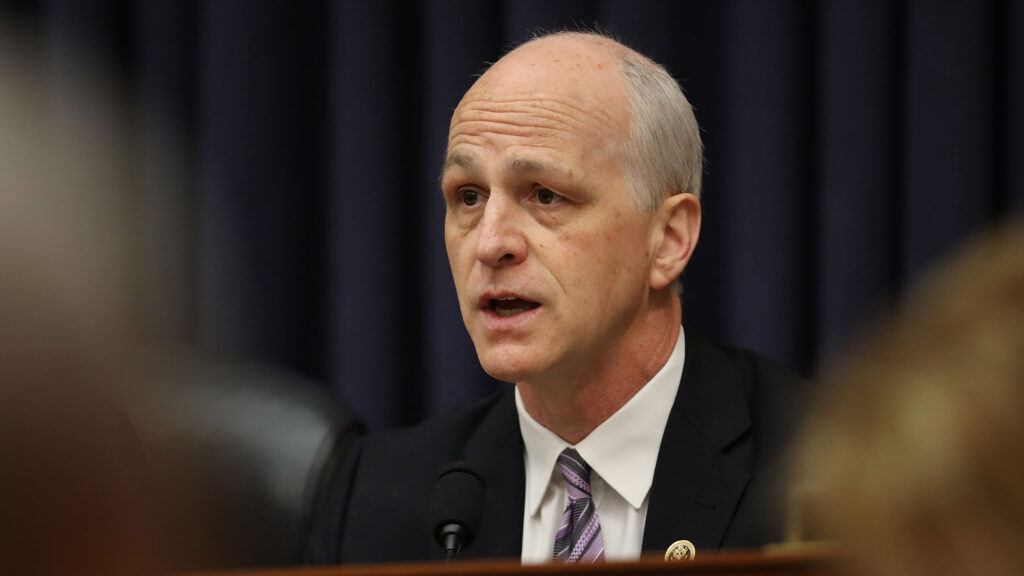

WASHINGTON — Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) knew when he hit rock bottom.

“I woke up one morning in early April of 2016 and seriously considered the possibility that I might never be able to get out of bed,” he opens his recent memoir, “Lost and Broken,” which details the six years in which “crippling anxiety” and chronic pain dominated his life even as he bounced back and forth from the Capitol to northern Seattle, the district he has represented for nearly three decades.

advertisement

Smith is the latest Capitol Hill lawmaker to open up about their struggles with mental health. Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman checked himself into a hospital for clinical depression this February, after a stroke last year. That, in part, prompted Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.) to open up again about her experiences with depression.

Their diagnoses are reflective of a national struggle to handle soaring depression and anxiety rates. One in five American adults reported depression diagnoses in 2020. The White House has labeled it a crisis particularly among teens and children reporting record levels of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.

Virtually everyone in Washington agrees that it’s a high-priority problem. But while the bulk of Congress is there — and last year passed a slate of bills to expand treatment, resources, and community programs — they splinter on why so many people, especially children, are plummeting into depression and anxiety. Pandemic shutdowns and social media use are the biggest targets in the sky, but they aren’t the only factors fueling the rise. Mental health experts and many Democrats also point to the political battle over gender-affirming care, worsening climate change issues, and bleak economic forecasts.

advertisement

It is emblematic of a small but growing fissure among policymakers and community leaders on how to deal with youth mental health issues.

Smith, for instance, represents one of the most diverse and Democrat-leaning districts in Washington state. He’s been a longtime advocate for mental health care resources, even as he struggled to admit his need for them. But in a recent conversation with STAT, he questioned whether young people are, in their openness about mental health, fixating on problems and not solutions.

“It’s awfully easy to simply focus on the negative. My big focus is how we can teach people to be more resilient at the end of the day,” he said.

The Washington lawmaker shared his thoughts on the biggest challenges to treating mental health, dealing with anxiety on the job, and the qualms he has with the current mental health conversation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

There have been lawmakers coming out more about their own mental health lately. You talk about stigma in your book and the kinds of processes that you had even as a mental health advocate. Do you think it is still risky for lawmakers or elected officials in general to talk about their own mental health?

I think there’s still a stigma out there, certainly. And forget lawmakers for the moment — just average individuals out there in the world. We all have an idea of ourselves, at every point in our lives. Something like this comes along and fundamentally alters the way people will look at you. That’s the fear: That I will be perceived differently, whether it’s job, friends, family. So you really kind of just sort of grit your teeth and hope it goes away so you don’t have to talk about it.

[The stigma] is coming down a little bit because a number of different people have been much more public about that. I think that’s helpful. The other piece that I think would be more helpful is to really focus on the process for getting better. I doubted that … that was my number one biggest thing, it’s, “like if this is wrong with me, I can’t change the way I feel.”

It does seem like the youngest generation, Gen Z, is beyond that stigma and talking about it a lot more, but also not necessarily getting the care that they need, even as they talk about it.

I hear what you’re saying. The younger generation is a lot more comfortable talking about literally everything going on in their lives. The world they grew up in drove a lot of that — I mean, the crazy crap that I did in high school didn’t wind up online for everybody to see. So there is certainly a greater openness, that’s one key part.

The part I worry about with the younger generation is that it seems like frequently it’s more of a lament than a, “Hey, what can I do to get better and become more resilient?” I want to move past [that and say], “Here’s the pathway to figuring it out.”

In general, it is positive [that] the younger generation is more open and honest. They’re not just holding it in. You do have to figure out how to be a productive human while you’re dealing with this as well. It’s a balance.

Congress did pass a pretty big package of mental health legislation at the end of last year and you’ve introduced some mental health bills this year as well. What do you think is going to be the most important measure for meeting mental health care needs?

I don’t know if it’s so much a matter of legislation. Certainly one big thing that we can do and have done starting with the Affordable Care Act is expand access, because access is an issue, but one piece of it.

The other thing is just sort of a cultural shift in all of our lives to begin viewing mental health maintenance in the same way that we view physical health maintenance. Teaching people from a very young age, here’s how you learn more about emotional intelligence, how better to handle your feelings. That’s the main shift we need in our society.

You became an elected official when you were 25. You’ve been doing this for a long time. How much do you think that this occupation, being out there constantly all the time, interacting on the campaign trail, might have contributed to, or even just exacerbated, your anxiety?

That’s a new one. And it’s a very fair way of looking at it. I don’t really think that it did exacerbate it, because the issues that I had were internal insecurities about my childhood, and things that I hadn’t resolved.

I guess being in public life, I had more opportunities for failure. That probably did put a lot more pressure on me — a lot of relationships to manage, speeches, human interactions, to this day. There’s a level of me that gets stressed by human interaction, which I know most people can relate to.

Now that I stop to think about it, you’re right. That probably did exacerbate it, because every moment, every day is like, “Oh my gosh, am I saying the right thing? Am I doing the right thing? Did I tweet that person properly or not?” It probably brought it to the surface.

Along those lines, do you feel like conversations among you and other lawmakers changed over these last few years as we talk about mental health more in the crisis that we’re having in America? Do you feel like there’s more personal conversations happening?

The best thing that a member has said to me — and this just happened like a month ago, after my book came out — my colleagues came up to me on the floor and said, “I read your book, and I just wanted to say, I’ve been struggling with a lot of those issues before. And I read your book, and I was like, it’s OK to talk about this.”

And I think what Fetterman has talked about, what others have talked about, a lot of people and members in particular said, “It’s OK to talk about it.” There’s still a lot of stigma, but it’s a lot less than it was, you know, three, four, or five years ago.

There was some criticism of Fetterman [when he checked into an inpatient program with severe depression] and questions about whether he was equipped to stay in office. What would your response be to that conversation?

It is a difficult conversation. There are responsibilities that come with the job, and if you are taking on an obligation, you have to be able to meet that obligation. Your mental and physical health is a factor in whether or not you’re able to meet that obligation.

I believe in the capacity of people to get better. I’m not going to just cut you off because you’re going through a problem. We should help people to get better and understand that nobody’s going to be perfect all the time. But when does it reach the point … [of] you’re not going to get better, can you do the job? Whether you’re talking about an elected official, job in an office, or a reporter, that’s judgments that hopefully the employer and the employee will make together.

Now, as an elected official, it’s a whole different thing. The voters elect us, and there’s no way to recall us as workers. If you vote for someone, you’re voting for two, six years. It’s up to the individual member at that point to determine whether or not he or she feels they can still be productive. I feel like I was still productive, even through the six years when I was, you know, impaired.

Obviously this is a really sensitive topic, but there has also been a big conversation about mental capacity for the job regarding Sens. Mitch McConnell and Dianne Feinstein. What you’re touching on is that there’s a responsibility to know when you have to back away from the role. Is that fair?

I think there is. But it’s a far more difficult question to ask than to answer. If you’re a journalist, you’ve got a turn in a column. You’re turning it in, or you’re not turning it in. And if you’re not, well, then we’re probably gonna have to move on.

As a politician, what is it that you have to do that one could measure in terms of what are you doing this? Are you doing that?

Do you think that someone like Sens. Feinstein or McConnell should step down?

It’s not my call. I’m not tracking day in and day out what they’re doing. It is up to them, their staff, and their constituents. They’re the ones they’re serving.

I do know that there are a lot of members out there who have had a perception that [they have] worked with them just fine. So I’m not going to comment on that. I don’t know enough about what’s actually happening.

There’s been increasing research into how climate change has affected mental health, whether it’s anxiety and depression, or even studies about climate change and dementia risk. How much do you think that even just climate change anxiety is potentially impacting people?

I’m interested in it, but the thing that really sort of drives me and I’m most passionate about, what I keep coming back to, is teaching people how to deal with life, not imagining that somehow, all the problems are going to go away.

You mentioned how the younger generation focuses a lot on being honest about things. They also focus a lot on the negative. I was reading something the other day about just a general Gen Z problem about affordable housing, and it talked about how this is the unluckiest generation. I was like, I don’t know. Other generations had two world wars, the Great Depression. Let’s get a little perspective here. Human existence has never been easy.

It’s awfully easy to simply focus on the negative. My big focus is how we can teach people to be more resilient at the end of the day. There are ways, as I outlined in the book, to teach your mind to be more resilient to deal with whatever is coming at you. Climate is a big cause of stress, to be sure. How do you deal with it?