Research into women’s health has long gone underfunded in the U.S. But there’s some optimism that might be changing, attendees to the first conference hosted by the White House on women’s health research said Dec. 11.

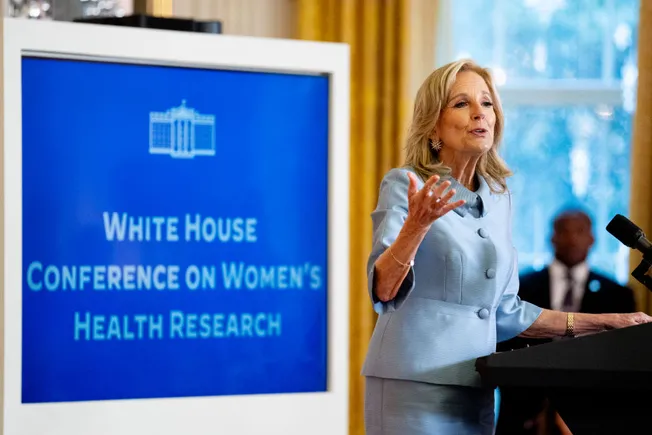

Both President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden spoke at the conference, which featured panels involving investors, physicians, advocates and researchers discussing innovation and investment in the field. The meeting follows the Biden administration’s announcement in February of the Women’s Health Research initiative, which committed $100 million to funding women’s health research through the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H.

“I think over the past year to year and a half, we’re really starting to hear about women’s health, and that is bringing the attention of other general investors into this space, which is exciting,” Johanna Grossman, co-head of healthcare and life sciences capital markets at the New York Stock Exchange, said at the conference.

Venture funding into women’s health startups has historically been low compared to other areas of the biopharmaceutical industry — although investment has trended upward recently. That funding deficit has meant less research and development for drugs that treated conditions primarily or exclusively affecting women, such as endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome. The exceptions to this are in oncology and in reproduction, which tend to draw the most attention.

“What’s fascinating about women’s health is how under-hyped of a category it is compared to its massive market potential,” said Jess Lee, partner and chief product officer at investment firm Sequoia Capital, during a panel Wednesday. “We’re talking about a market that affects half of humanity, yet the sector has remained underfunded and under-invested in.”

“What we found is sometimes the most under-hyped sectors are the best places to build very large businesses,” she added. Sequoia has invested in Maven, a women’s health telemedicine network, and Natera, which provides DNA testing for prenatal screening and hereditary cancers.

Still, relatively few venture capitalists are women, an imbalance that may play a role in shaping how much firms invest in women’s health. “Venture firms are realizing they have to hire women who will see these [investment] opportunities,” Lee said.

Wednesday’s conference spotlighted federal efforts around women’s health, but those efforts could also catalyze greater private investment.

“The addition of government funding from the White House, from the [National Institutes of Health] is also attracting private capital because in some ways that helps to subsidize some of the research that’s desperately needed,” said Grossman.

One challenge is how, in women’s health, there are “no real established benchmarks for investors to grab on to,” Grossman added. With the biotechnology sector still recovering from a market downturn, venture firms may balk at putting money into a sector where returns via initial public offerings or M&A are less certain.

Still, Grossman remains optimistic. “I’m super excited at the fact that there are about a dozen biopharmas in women’s health areas, or developing a women’s health product, that received over $50 million in venture funding this year alone,” she said.

Hanging over the conference, though, was the looming presidential transition. It’s not clear whether President-elect Donald Trump would extend the Biden administration’s work on this front, or whether Congress would take up President Biden’s call for more funding for women’s health R&D.

“My work doesn’t stop in January when Joe and I leave this house,” Jill Biden said. “I will keep building alliances like the ones that brought us here today, and I will keep pushing for funding for innovative research.”