Want to stay on top of the science and politics driving biotech today? Sign up to get our biotech newsletter in your inbox.

Hello! A thought: I moved to San Diego last year and am always on the lookout for interesting news. If you’re here, reach out! In today’s newsletter, we discuss embryonic stem cell ethics, learn of parents searching for a treatment for their son’s ultra-rare neurological disease, and more.

advertisement

The need-to-know this morning

- BridgeBio sold European marketing rights to acoramidis, its treatment for a form of progressive heart disease, to the German pharma giant Bayer. Under terms of the commercial licensing deal, BridgeBio will receive $310 million from Bayer in an upfront payment and will be eligible for royalties starting in the 30% range on acoramidis sales in Europe. European regulators are reviewing the drug, with a decision expected in 2025.

Longer treatment, less MASH

That’s the simple, take-home point from Akero Therapeutics this morning. Extending treatment with its experimental drug for the liver disease known as MASH from six months to two years resulted in better outcomes for patients — most notably reductions in liver scarring at a rate three times higher than placebo without worsening other symptoms.

The mid-stage study of Akero’s drug, called efruxifermin, achieved its main goal in September 2022. With longer treatment, more patients with MASH responded to the drug, while those who initially benefited showed durable improvements.

“We’re really pleased with the data. It’s exactly what we were hoping to see,” Kitty Yale, Akero’s chief development officer, said in an interview with STAT. “It’s not just the high response rates, but the fact that responses are sustained and broadened as well.”

advertisement

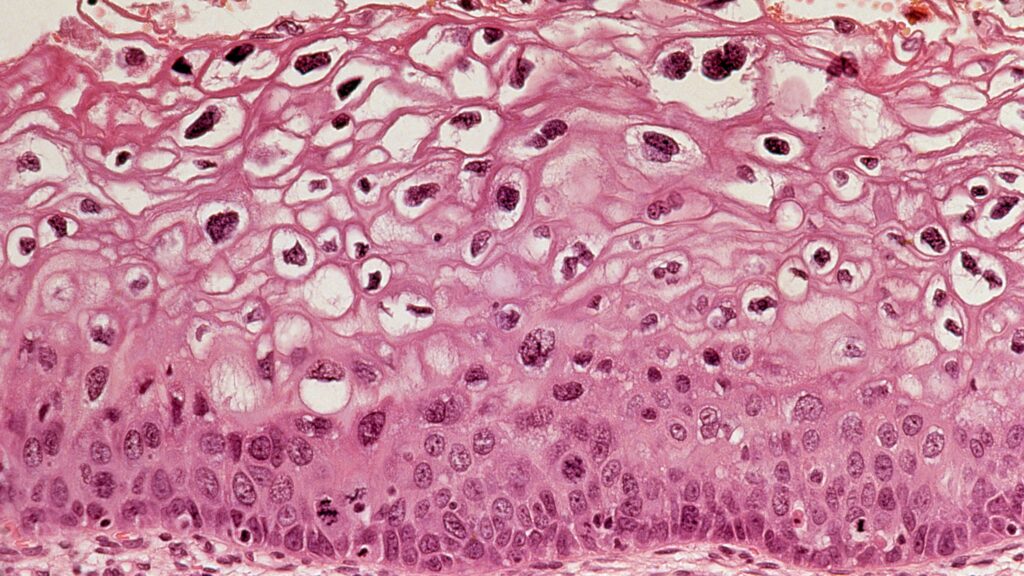

How human embryo models could advance medicine

Stem cell biologist Jacob Hanna, who is on this year’s STATUS List, is known for having grown a synthetic human embryo without using a sperm or egg cell. He recently spoke with STAT about the ethics of such research, and how human embryo models could help advance the field of organ transplant.

“They’re very fascinating creatures,” Hanna said of embryonic stem cells. “They can make an entire embryo on their own. Basically, we unveiled that encoded within them is a self-propagating reaction or domino effect.”

Hanna’s team has thus far grown synthetic embryos to the equivalent of 14 days of gestation — right before organs form — but wants to push it to 40 or 50 days next. These embryos might be particularly helpful for advancing science, he said. A skin cell could ultimately be coaxed into a blood transfusion or organ transplant, or even be used in IVF.

“There’s a need to understand human development,” he said. “And we explain to the public there is no other way than doing it. I’m not saying that it has no ethical price at all, but I do think it does alleviate the difficulties of dealing with aborted embryos and donated embryos and so forth.”

Parents race to fund treatment for ZTTK syndrome

The parents of Lucas Guo, a 19-month-old with one of the rarest neurological diseases in the world, are trying to raise $10 million to spur the development of a treatment or cure for their son. The condition, called ZTTK syndrome, is caused by a genetic mutation — and so his parents are contacting scientists, venture capitalists, nonprofits, and other rare disease advocates to try and save Lucas.

“What we’re trying to do is bend the time curve by working hard with scientists and other collaborators in this ecosystem to accelerate the understanding,” Ada Lio, his mother, told the Boston Globe.

Although Lucas’s disease is rare, there are many children with such diseases — and there’s a growing demand for ways to tailor complex therapies to individual mutations.

Serum Institute of India wants government HPV contract

The Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest maker of vaccines, is ramping up production of an HPV vaccine to help a government initiative there to prevent the cancer-causing virus. The vaccine is India’s first homegrown shot against HPV, and is available on the private market for 2,000 rupees.

“Our capacity at the moment is just a few million doses but the demand is infinite. If we were to roll out 50 million doses in India, they would be used up, both in the private market and the government procurement scheme,” CEO Adar Poonawalla told Reuters.

The Indian government plans to administer the HPV vaccine to girls between the ages of 9 and 14. The Serum Institute still doesn’t have a contract with the Indian government; companies like Merck and GSK, which also make HPV vaccines, could also bid for contracts. Poonawalla said his company would make the vaccine about eight times cheaper when supplied to the government; it plans to export HPV shots to other countries in 2026.

More reads

- Federal regulators, scrambling to keep up with AI in health care, team up with industry to set standards, STAT

- FDA approves Johnson & Johnson’s Rybrevant for lung cancer treatment, MarketWatch

- Missing data is making it difficult for the pharmaceutical industry to help LGBTQ+ people, STAT