Independent studies suggested that spinal cord stimulation improved chronic pain no more than placebo, but industry-funded critics cast doubt on these findings, researchers said.

Recently published papers “found evidence of no benefit on pain and risk of harms,” wrote Adrian Traeger, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia, and Lisa Bero, PhD, of the University of Colorado in Aurora, in a JAMA Internal Medicine viewpoint article. “Authors funded by the spinal cord stimulator industry were swift to respond.”

“The responses to recent research on spinal cord stimulation illustrate how corporations continue to undermine independent science,” Traeger and Bero observed. “At a minimum, readers should recognize that attacks on independent science are often sustained and repetitive industry tactics to protect profits and should discount these criticisms.”

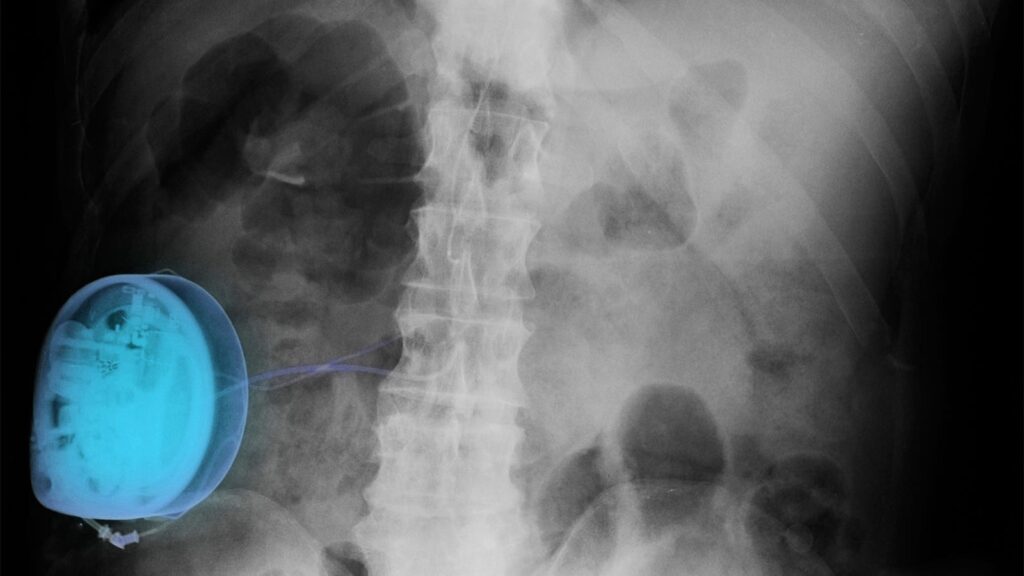

Spinal cord stimulation is a costly and invasive procedure and “clinicians and patients need to know what the evidence says about likely benefits and harms,” Traeger noted in an email to MedPage Today.

“As with many procedures to manage chronic pain, there are cases and anecdotes of people improving with spinal cord stimulation,” he continued. “But the best evidence available — from a Cochrane review — suggests that these devices may work no better than a credible placebo. Serious adverse events include infection, lead migration, neurological damage, and re-operation.”

A 2023 Cochrane review of randomized trials led by Traeger reported that data did not support the use of spinal cord stimulation to manage low back pain outside a clinical trial and concluded that spinal cord stimulation probably did not have sustained clinical benefits that would outweigh its costs and risks. A 2001 Cochrane review, which Traeger was not involved in, found very low‐certainty evidence that spinal cord stimulation may not provide clinically important benefits on pain intensity compared with placebo.

In JAMA Neurology, a retrospective comparative effectiveness study showed that the use of a permanent spinal cord stimulator was not associated with a reduction in opioid use or nonpharmacologic pain interventions compared with conventional medical management. Nearly one-fifth of patients treated with spinal cord stimulators experienced complications and required device revision or removal.

And in JAMA, a randomized clinical trial of patients with chronic radicular pain after lumbar spine surgery showed that spinal cord burst stimulation led to no significant difference in back pain-related disability compared with placebo. A follow-up study showed similar results.

Traeger and Bero identified 18 critiques in academic literature of the Cochrane reviews and the JAMA and JAMA Neurology articles. “Industry-funded critics of independent studies often do not follow the usual route of scientific discourse,” they reported.

“Rather than respond to the journal where the original study was published, critics frequently publish in journals where they are the editors and can control the discourse (15 of 18 letters criticizing the independent studies cited in this article appeared in journals with industry-affiliated editors),” they wrote. “The journal can then choose to paywall the subsequent response from the independent authors, giving critics the last word.”

Other strategies included attacking the credibility of the researchers instead of the research and criticizing the Cochrane reviews for assessing clinical trials instead of real-world studies.

Critics also claimed that because the FDA had approved spinal cord stimulators and they’ve been used for decades, there already is evidence for efficacy and safety.

“This is not the case,” Traeger and Bero wrote. “Provision 510(k) requires that new medical devices need only be ‘substantially equivalent’ to a product already on the market, even if the earlier product is itself untested.”

Part of the concern may stem from the small number of trials comparing spinal cord stimulation and placebo, suggested Shravani Durbhakula, MD, MPH, MBA, of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and co-authors in a critique of the 2023 Cochrane review published in Pain Medicine.

While Durbhakula and colleagues have ties to industry, they pointed out that independent physician investigators have struggled to complete these studies. “Meanwhile, industry is disincentivized from performing such studies, as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration does not require them for regulatory approvals in the presence of a predicate device, they are costly and hard to accrue patients into, and the risk-benefit ratio does not favor companies and their shareholders,” they wrote.

In the 1950s, the tobacco industry used campaigns of criticism to defend their products, Traeger and Bero noted. Other industries have used similar approaches to cast doubt on independent studies, they added.

Debate is an important part of the scientific process, Traeger pointed out. “When corporations interfere with the scientific process, it puts patients at risk,” he said.

-

Judy George covers neurology and neuroscience news for MedPage Today, writing about brain aging, Alzheimer’s, dementia, MS, rare diseases, epilepsy, autism, headache, stroke, Parkinson’s, ALS, concussion, CTE, sleep, pain, and more. Follow

Disclosures

Bero is senior research integrity editor for Cochrane, for which the University of Colorado receives remuneration outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Primary Source

JAMA Internal Medicine

Source Reference: Traeger AC, Bero LA “Corporate influences on science and health: the case of spinal cord stimulation” JAMA Intern Med 2023; DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.6962.

Please enable JavaScript to view the