I was living on the precipice of end-stage disease when I enrolled in the clinical trial that resulted in the historically fast Food and Drug Administration approval for the game-changing cystic fibrosis drug Trikafta. Five years later, the worst parts of my CF are gone. I recently recovered from a viral infection that provoked a pneumonia-like illness without landing in a hospital tied to an oxygen tank. A decade ago, I would have had a vastly different outcome. Along with hundreds of other people with CF, I have also become a parent since Trikafta hit the market. The CF community’s baby-boom we’ve all worked toward has happened thanks to this drug.

But access to Trikafta is now at risk for several hundred people with CF, because of what some might consider to be good intentions.

advertisement

Frustrated with rising health care costs, several state governments have created bureaucratic agencies called Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) to impose European-style price controls on prescription medicines.

Like the name implies, these boards are designed to bring drug prices down, but in doing so, they are taking an oversimplified view.

Board mandates vary state to state, but the PDABs follow a similar assessment playbook, one that has led to meaningful drug launch delays and patient access challenges abroad. Why expect anything different here?

advertisement

In Colorado, the local PDAB selected its first five drugs to review: Enbrel, Genvoya, Cosentyx, Stelara, and Trikafta. Next the board will determine a ceiling amount that an insurer can pay for each drug.

Colorado’s actions could actually jeopardize access to these drugs not just in Colorado but across the country. This is because by law, Medicaid gets drug companies’ “best price,” a 23.1% discount off the drug’s lowest list price given to any other purchaser. If Colorado’s PDAB determines that the insurance plans it governs must buy any drug at a substantially lower point than its current list price, then the new price could “cascade” into the Medicaid market, forcing drugmakers into a serious tradeoffs: reduce their Medicaid prices accordingly or leave the Colorado market to avoid triggering a Medicaid best price recalculation.

The latter is a risk America should be unwilling to accept.

Colorado’s PDAB considers several variables during its affordability review, but one in particular, “paid per-patient per-year,” is leading the state down this dangerous path.

A small number of people, by definition, use rare disease drugs, and so these medicines require high per-patient prices while they’re on-patent to incentivize their development.

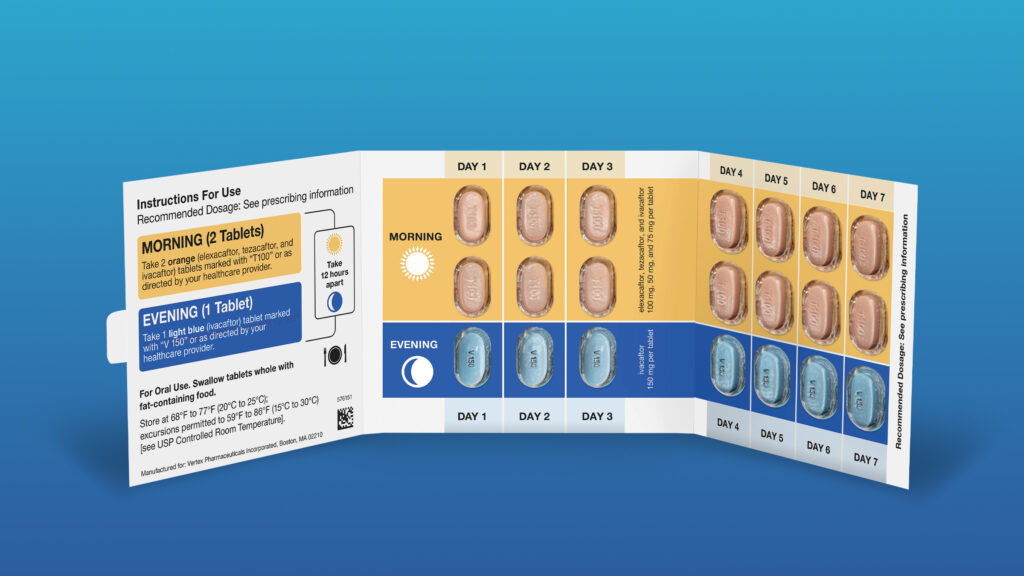

Take Trikafta as an example. It is a daily pill that treats CF, a rare disease that has historically robbed patients of their lives before their 30s. It is a remarkable drug that saved my life, and plainly, it is the wrong target for Colorado’s bureaucrats.

Trikafta is taken by only a few hundred Coloradans, and so its list price of more than $300,000 per year seems exceptionally high. This simple fact skews the per-patient metric, so some states have chosen to exclude rare disease drugs from their PDAB evaluations. Colorado’s decision not to represents a direct attack on rare disease communities.

Medical care, including some drugs, can be prohibitively expensive for those of us who need it at any one time, but that is precisely why we all buy insurance. And Trikafta is an example of a medicine that is widely accessible because insurers have decided the drug is worth covering. For most of us, the monthly copay, which is the true lever of health care affordability, is quite manageable after copay assistance. Mine has historically been about $30. For some, the copay is even less. Moreover, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s annual patient registry report further shows a high utilization rate of more than 90% of eligible patients for the drug.

Drugs like Trikafta will not be expensive in perpetuity. When Vertex’s patent on the medicine expires in 2037, society will reap one of the key benefits of small molecule medicines: competition from generic versions will drastically reduce its price, eventually by more than 90%.

Future generations of CF patients both inside Colorado and across the globe will continue to be free from the worst parts of CF thanks to generic Trikafta, while state and commercial payers will manage CF care at a fraction of today’s cost.

In fact, this symbiotic relationship between payers and drugmakers is quantifiable, yet often overlooked. One analysis shows the long-run value Trikafta provides to patients and society. When real world variables like genericization, pharmaceutical rebates, and future patients are inputted in Trikafta’s value assessment, this more comprehensive analytical framework than the one PDABs rely on reveals the drug is cost-saving for society relative to all the medical care the CF population has historically required.

By only considering today’s drug prices and working towards upper price limits from them, the Colorado PDAB math risks being woefully incomplete, and does a massive injustice to prescription drugs’ unique long-term value proposition.

I have watched CF end lives far too early, crush dreams, and unleash unspeakable horrors on those who suffer from this god-awful disease. But I have also seen, and lived through, one of medicine’s greatest achievements.

Is that not the reason we demand pharmaceutical interventions for otherwise life-shortening conditions?

My story and concern are not unique. Patients across the country are warning states against moving forward with PDABs that aim to import a European-style methodology designed to be hawkish against rare disease drugs in places, including Oregon, Minnesota, Maine, Maryland, and elsewhere.

While Colorado’s affordability board has commented that they don’t necessarily need to include a price-cap following the review, their process represents an unnecessary risk to CF patients for whom access is largely not an issue, and yet were condemned to short lives before Trikafta was developed.

Taking on the pharmaceutical industry might score easy political points for policymakers, but at what cost? Politically motivated drug arbiters abroad are already harming patients. We can’t let that happen in America. That we even have a widely accessible drug like Trikafta should be evidence enough the market is functioning. Rare disease patients deserve better than watching bureaucrats take a political victory lap.

Gunnar Esiason, a patient advocate living with cystic fibrosis, is the Director of Patient Engagement at RA Ventures. Neither RA Ventures nor any of its affiliates own securities issued by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Esiason’s family foundation, the Boomer Esiason Foundation, has previously accepted donations from United HealthCare and Vertex Pharmaceuticals.