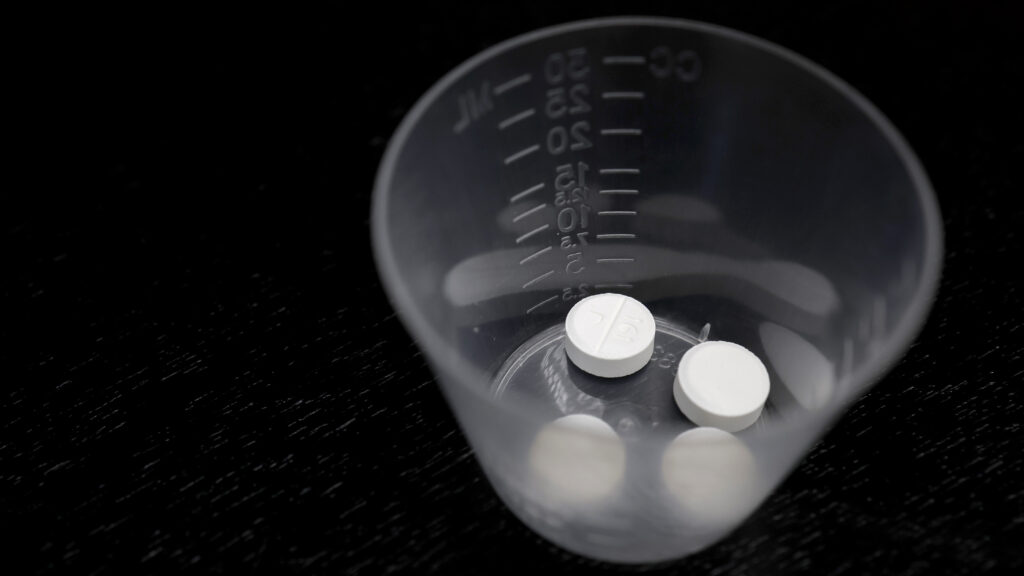

Margaret Carpenter, based in New Paltz, New York, has been indicted for prescribing abortion pills to a person in Louisiana — where nearly all abortions are illegal, even in cases of rape or incest. It isn’t the only legal threat she faces: In December, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued Carpenter for sending abortion pills to someone in the state. On Thursday, a judge fined her more than $100,000 and ordered her to stop prescribing and mailing abortion drugs to Texas patients.

I know Carpenter as “Dr. Maggie.” She has been a hero of mine for a long time, but not just for standing up for people’s rights to reproductive health. When I was 35, she helped save my life.

advertisement

She has saved countless others, too, working to prevent cancer in places like Senegal and Ethiopia. Yet religiously and politically motivated law and the opinions of people who don’t know her, in a state she does not reside in, have resulted in an arrest warrant for her. Her critics accuse her of “ending” a life. But the trajectory of her career clearly illustrates a doctor with an unwavering commitment to saving people’s lives, including mine.

In the 2000s, when I was in my 30s, it wasn’t easy to find a primary care physician who would see new patients in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Somehow, I found Dr. Maggie, a brilliant, kind, and skillful doctor.

At 35, I began to experience abdominal pain and challenges with bowel movements, including both an urgency to use the toilet and difficulty once I got there. I finally told a nutritionist I saw regularly — a doctor — about the symptoms I’d now suffered for months. His response was to put me on a “cleanse,” during which I lived on water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, and maple syrup. After all, I was only 35 years old. How sick could I be?

advertisement

Despite some temporary relief, a few weeks later, I was still experiencing troubling pain. When the pangs repeatedly woke me up one night, making it impossible to sleep for more than a few hours at a time, I conceded to my boss at the book publishing company where I worked that I needed to take a day off for a doctor’s visit. Dr. Maggie saw me right away.

These days, I find it nearly impossible to get in to see a primary care physician when I’m sick. The last time I did see one in person was only because I literally went to the office unannounced and pleaded my case to a sympathetic assistant. They managed to squeeze me in.

Dr. Maggie always saw me when I needed her.

When I walked into her cozy first-floor office that day, embarrassed to have called in sick, Dr. Maggie immediately knew that something was wrong — that I needed care right away. She pointed me to a gastroenterologist, and within days, I was diagnosed with stage 3 colorectal cancer. I had two different tumors, one in my colon and one in my rectum, that had grown independent of one another. Dr. Maggie was right. Something was terribly wrong.

Because she intervened when she did, I was able to get treatment. Had my disease developed into stage 4 cancer, it would have been more challenging to treat. My chances of living would have been significantly slimmer. She put my care — and her medical knowledge — first when I made my appointment with her, when I went to see her, and when she made sure that my next step was to see a gastroenterologist. A year later, I had no sign of cancer. That was seventeen years ago, and so far, I’ve remained cancer-free.

Even though it was unlikely that a 35-year-old had colorectal cancer (though the rate among young adults is increasing), she listened to me, recognized my symptoms, and took the appropriate next steps. She operated only in the interest of helping me. Yet today, there is an arrest warrant for her because it’s believed she provided the same level of care to someone states away — in Louisiana — who she didn’t know but wanted to help.

advertisement

Without Dr. Maggie’s intervention at that time in my disease’s progression, the cancer would have continued to spread; my chance of survival diminished. This is why I credit her with helping to save my life.

Eventually, Dr. Maggie and I both left Park Slope and moved to the Hudson Valley, like so many other Brooklynites. Though I wanted her to remain as my doctor, she was now focused on helping people much less privileged than I. She founded the organization Go-Doc-Go in 2013 and began traveling to far-away places, like Africa, to help prevent cervical cancer.

Just a few months ago, in the fall of 2024, Go-Doc-Go visited Senegal, their team working in multiple locations, and donating valuable medical equipment to prevent cervical cancer. Fourteen physicians were trained to operate LEEP machines (used to cut away abnormal tissue from the cervix, preventing the growth of cervical cancer), and 81 midwives were trained to screen for cervical cancer and treat lesions with thermal ablation.

Dr. Maggie is responsible for saving the lives of people around the world, including my own. Yet, Louisiana alleges she is a criminal. The reality in 2025 is that, according to the law, if she did send the pills, she technically is a criminal — even if just a few years ago, she wouldn’t have been. It’s unjust — and bad for public health. Why should the government have a greater say in a person’s medical care than a doctor?

Luckily, in New York state, Dr. Maggie is protected by a shield law. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has stated that she will not sign an extradition request to send Dr. Maggie to Louisiana. Still, I worry for Dr. Maggie.

If helping others and saving lives are crimes, perhaps we should all be criminals. Today, I am a cancer-free 52-year-old, enjoying my life in the Hudson Valley, living across the river from Dr. Maggie, happy that she is now devoted to providing care to those with barriers to reproductive health. Had she not recognized I was sick when she did, this day might not have come.

advertisement

Maya Gottfried is the author of three books for children (published by Knopf), in addition to articles and essays published by Oprah Daily, Los Angeles Magazine, and Upstate House.