Over the past several months, my conversations with colleagues in the Alzheimer’s field have featured an unusual sentiment: optimism inflected with worry.

Optimism because, after years of failed studies and the disastrous accelerated approval of aducanumab, we’re enjoying a less than one-year-old streak of good news. The latest bright flash is the June 9 Food and Drug Administration hearing on the anti-amyloid antibody lecanemab (to be sold by Eisai as Leqembi). The committee members unanimously agreed that the drug outperformed placebo on multiple measures of cognition, day-to-day function and biomarkers. It’s beneficial. Full approval is almost a certainty. If donanemab’s similar results hold up to scrutiny (the data are limited to a press release, they’ll be presented in full at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in July and in a forthcoming paper), it will likely enjoy the same decision.

advertisement

So why worry?

Lecanemab and donanemab present the same risks to the brain: microscopic hemorrhages and swelling. At the FDA advisory committee meeting, the discussion of these side effects’ likelihood and how best to mitigate them was thoughtful but incomplete. It was incomplete because it didn’t take on the totality of the problem.

The problem isn’t the drugs. It’s the drugs in the system.

advertisement

Here’s my worry as an Alzheimer’s expert practicing at a memory center. In the months after the drugs are approved, news organizations will recount the sad stories of patients who received a prescription that was neither reasonable nor necessary. They were prescribed the drugs following sloppy diagnoses and went on to suffer risks that weren’t properly mitigated. Skeptics will gesture to aducanumab and parade these stories as further evidence these anti-amyloid drugs “don’t work” or are “too risky” and so a waste of Medicare resources.

I also worry about the patients who could have benefited from the drugs but were misdiagnosed. They won’t make the news, but they’re another example of the unfortunate outcomes of multiple converging circumstances that threaten to wreck the progress we’ve achieved.

The problem of the drugs in the system begins with diagnosis. These drugs were tested in people with a clinical diagnosis of either mild cognitive impairment (widely known as MCI) or mild stage dementia and positive Alzheimer’s biomarkers — beta-amyloid, of course, because the drugs target that pathology. The study of donanemab also required patients to have a marker of tau pathology. The workup to make these diagnoses accurately is complicated and time-intensive.

Unlike in most adult medicine, in my field we have to gather history from both the patient and a second source who knows the person well, like a family member or close friend. We need detailed cognitive testing. The biomarkers, measured using PET scans or spinal fluid studies, require careful interpretation. My colleagues and I typically need at least an hour to gather these data and additional time to review them.

These new drugs mean more real harms from mis- or missed diagnosis. A missed diagnosis (“It’s normal aging …”) sends away a person who might benefit from an effective treatment. A false positive diagnosis will unnecessarily expose a person to the drugs’ risks.

Those risks are to the very same organ the drugs treat.

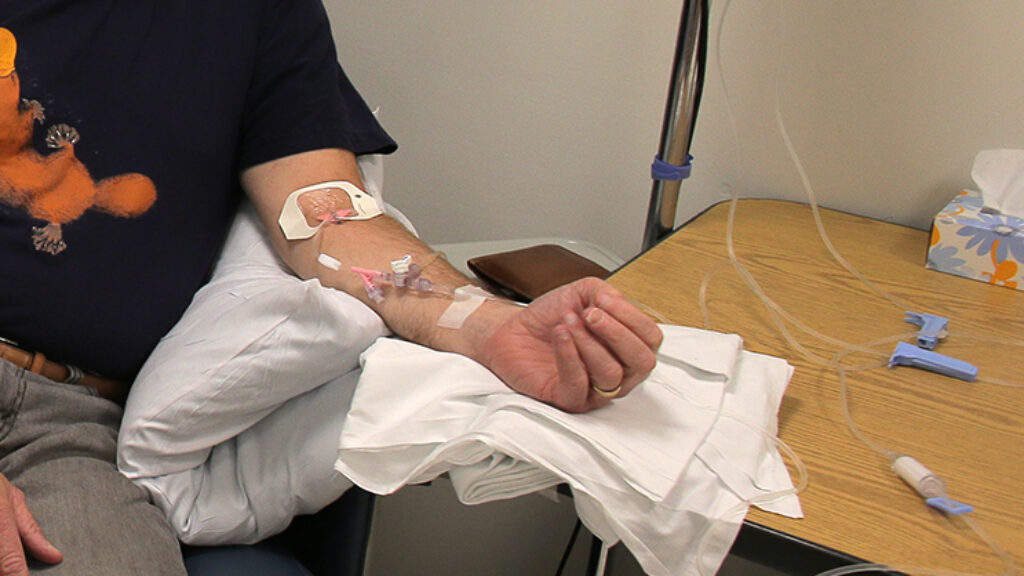

Microscopic bleeds and swelling are typically detected only using an MRI scan. Sometimes, a patient experiences symptoms, but when they happen, they’re typically common, nonspecific problems such as a headache. Often, they’re asymptomatic.

Once detected, physicians must conduct careful assessment to decide whether to continue the drug, pause or stop treatment. Some patients do suffer devastating outcomes. Dan Gibbs, a physician with Alzheimer’s who was treated with aducanumab, experienced bleeding and swelling so severe he required ICU care, followed by weeks of slow recovery. Patients on both donanemab and lecanemab have died.

These risks are associated with identifiable patient characteristics. They may be increased in people with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a brain disease that causes microscopic brain bleeds (22% of persons with Alzheimer’s disease have CAA detected by MRI), or who are taking anti-coagulant medications to prevent stroke. I write “may” because the lecanemab study excluded people with more than four microhemorrhages and included only 5% were taking anti-coagulants.

What’s quite certain is the risk is associated with having the e4 variant of the ApoE gene. In addition to excluding persons with more than four microhemmorhages, the Veterans Administration’s criteria for the use of lecanemab excludes people with two copies of the e4 gene.

Ironically, Apoe4 is also a common and well-described risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s (69% of the persons in the lecanemab trial were ApoE carriers). A patient who learns she’s an ApoE carrier now has information about her biological relatives’ potential risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. ApoE testing has a double effect: It informs a personal risk-benefit assessment and a family assessment of Alzheimer’s disease risk. For some family members, this can be a stigmatizing experience. Apoe4 carriers report worrying about their cognitive abilities and how others such as friends and co-workers will treat them if they know the result.

The FDA hearing revealed conflicting conclusions about how to manage the associations between these risks and ApoE4, CAA, and anti-coagulation medications. Some members wanted ApoE testing required and tight restrictions on people with CAA or using anti-coagulants. Others did not. All agreed that patients must be informed of what’s known and also what’s unknown, and that real-world observational data are needed.

So those are the risks. What about the benefits?

The measures of the benefits of a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease are difficult to translate into practice. The benefit of cancer treatments such as CART-T is measured with a simple language: Patients live longer. That’s easy to measure and to understand.

In dementia treatment, survival has never been measured as a benefit. Instead, we speak of living longer in a certain state of mind. The measures we use — cognition and day-to-day function — and the significance of changes in them aren’t readily understandable. The primary endpoint of the lecanemab trial, the Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), isn’t used in clinical practice. Most patients and clinicians haven’t a clue what it is. Measures of caregiver outcomes such as burden are similarly opaque.

The result? Incessant debates over “clinical meaningfulness” that sustain the argument the drugs are “too risky” because if you can’t understand the benefits, then all you see is the risks.

Benefit also matters to insurers like Medicare that pay for these very expensive drugs. Eisai has priced Leqembi at $26,500 per year. This cost, together with the challenging language of benefit, has instigated sharp debates over cost effectiveness. Medicare, though forbidden to use cost as part of its rationale for coverage decisions, wants data to inform whether the drugs are reasonable and necessary. It recently reiterated its plans for “coverage with evidence development.” This unusual requirement will reimburse the drugs only to people enrolled in a registry whose data can inform knowledge about the drugs’ risks and benefits.

At heart, we have a numbers problem here.

Alzheimer’s is a prevalent disease. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Americans could be taking these drugs, but as a 2017 RAND report concluded bluntly, “the U.S. health care system is ill-prepared to handle the potentially high volume of patients who would be eligible for treatment.”

Most primary care clinicians are uncomfortable making a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, feel unprepared to care for these patients, and lack specialists to assist them. But most neurologists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychiatrists are not adequately skilled to prescribe these drugs, either. Even if they were, there simply aren’t enough of these professionals. Moreover, there’s no established criteria that define an Alzheimer’s clinical expert. Training in those disciplines is necessary but not sufficient, especially to assure these novel and complicated drugs are prescribed reasonably.

Let’s take stock: The workup of mildly symptomatic presentations of memory loss is tricky and time-intensive, biomarker testing carries nuance, the drugs’ risks can be serious and are associated with a gene for Alzheimer’s disease and may be heightened in persons on anti-coagulants and CAA (we need to know more), the measures of value are difficult to translate into clinical practice and policy, Medicare wants patients enrolled in a registry, the drugs’ costs are notable, and there are lots of patients and not enough clinicians to accurately diagnose and treat them. Finally, the risks are vivid, and they happen within the first few months of treatment. The benefits of disease slowing, in contrast, are far less evident.

Now, you understand why my colleagues and I worry. If we’re going to have the better drugs, we need a better system, too.

There are several compelling technological solutions that can minimize misdiagnosis, reduce the time and effort of a workup, educate patients and families, and mitigate risks. They include telemedicine for central reads of MRI scans, access to experts, and remote patient education and provider training; remote and passive technologies to measure cognition and day-to-day function; and blood tests for Alzheimer’s biomarkers. Scaling these technologies is largely an engineering problem that will take time. We could initiate a longshot moon-shot style “set a deadline and get to work” project to hasten it.

These fixes also necessitate changes to laws and regulations about privacy, data flow, and professional licensure. Telemedicine stands out. We have to overcome the bizarre 19th century-era, state-based medical licensure system. I, for example, in my Philadelphia office cannot practice telemedicine with a patient who lives 10 miles across the Delaware River in New Jersey but I can with a patient hundreds of miles away in western Pennsylvania.

There is one solution that can happen right now. It’s in the hands of the FDA. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy, widely known by its abbreviation REMS, allows the FDA to strike a drug-specific balance between access and safety. Since 2007, the FDA has developed 306 such plans. A REMS details requirements such as education and monitoring to prevent, monitor, or manage a drug’s risk.

For instance, after the beneficial MS drug Tysabri was discovered to cause the rare but serious brain infection with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a REMS known as the Tysabri Outreach Unified Commitment to Health (TOUCH Prescribing Program) saved it from withdrawal. REMS have also been used in drug approvals that engage politically fraught topics, such as the approval of mifepristone, one of the pills used for medical abortion.

At the June 9 FDA hearing, no one spoke explicitly of a REMS, but the idea still swirled about. To mitigate risks, committee members suggested a phone call from the clinic after treatment to check for symptoms of brain bleeding and swelling; clear and concise warnings about the known and unknown risks related to ApoE, CAA and anti-coagulation; and more data from observational studies. A REMS can do these.

Other features could include clinical centers signing off on their capacity to provide services and criteria for prescribing physicians, such as training in geriatrics, neurology, or psychiatry and self-declared experience in diagnosing MCI and dementia caused by Alzheimer’s and related diseases. The discussion, recommendation for, and decision whether to pursue ApoE testing should also be documented in a REMS.

The need for “real-world” data was a repeated point at the June 9 hearing. A REMS is a tested method to gather these data. All providers will have to participate in a database that captures key patient characteristics — such as whether the person is an ApoE4 carrier, has CAA, and uses anti-coagulant drugs — and their MRI imaging results with attention to evidence of microhemorrhages and what symptoms they experienced. This would likely satisfy Medicare’s coverage with evidence development requirement for a registry. In fact, Medicare and the FDA might actually design it together.

I’m optimistic. Some patients will benefit from these drugs. But I’m also a realist. Some patients will be harmed.

A REMS will mitigate the worry that these harms shouldn’t have happened. With it in place, we’ll have confidence and trust that the system did its best with the resources we have — and we’re learning to do even better.

Jason Karlawish is a professor of medicine, medical ethics and health policy, and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and co-director of the Penn Memory Center. In the past two years, he has been a site co-investigator on clinical trials sponsored by Biogen, Eisai, and Lilly.