When I was a medical student in the 1980s, the school hired “pelvic instructors” who taught us how to do exams in a painless and respectful way. They even allowed us to perform practice examinations on them.

But at the same time, senior doctors urged me to perform pelvic exams on anesthetized women about to get surgery — women who never gave consent. Indeed, despite decades of objections, pelvic exams without consent have continued to occur, leading the Department of Health and Human Services to issue new guidelines earlier this year that mandate the “explicit consent” of patients.

advertisement

Of course, the pelvic exam’s complicated and fraught status is hardly a surprise. As historian Wendy Kline writes in her new book, “Exposed: The Hidden History of the Pelvic Exam,” the medical procedure is a “window” into meaningful questions about gender, medicine, and power. And the choices made, and the controversies that occurred, reflected the historical eras in which they occurred.

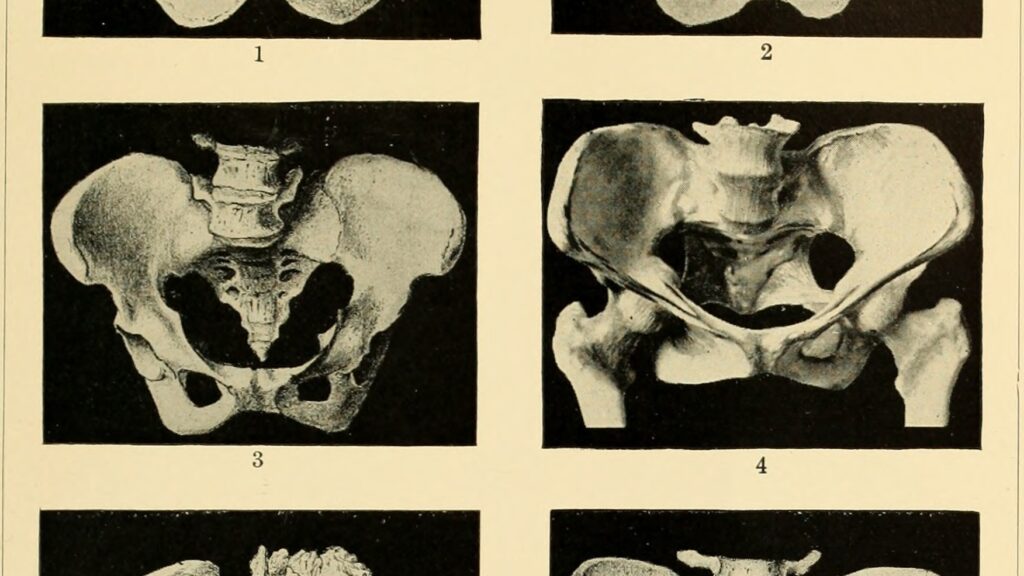

The modern history of the pelvic exam began in the mid-19th century when a Southern physician named J. Marion Sims invented and popularized an early version of a speculum that could be used to examine a woman’s vagina. The speculum enabled him to see a woman’s anatomy much more clearly, whether healthy or diseased. The speculum was essential to Sims’ invention of an operation to cure the vesicovaginal fistula, an extremely unpleasant condition in which urine from the bladder leaks into the vagina due to trauma during childbirth.

So far, so good! Having invented a game-changing device and cured a dreaded disease, Sims was well on his way to becoming the “Father of Gynecology.” In 1894, a statue of Sims was even erected in New York City’s Central Park.

advertisement

But with the rise of second-wave feminism in the 1970s, scholars began to take aim at Sims. Most egregiously, he had perfected his new operation on enslaved women, without anesthesia, often operating multiple times on the same individuals. The women, three of whom were named Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey, had been unable to resist Sims’ demands given the racist society in which they lived. Sims himself was a slave owner and a fierce defender of slavery. In 2018, the Central Park statue was removed due to his “egregious misuse of power in conducting surgical experiments on enslaved black women.”

Unfortunately, Sims was only one of many male physicians whose seemingly scientific interest in pelvic exams obscured more nefarious actions. There have also been numerous examples of doctors treating the exam as some type of sexual experience for themselves, taking advantage of their power and women’s fears about speaking up. Perhaps the most notorious example of this are the crimes of Larry Nassar, a sports medicine specialist who was in charge of treating injuries for the U.S. women’s gymnastic team. Nassar, who is serving a decades-long sentence for criminal sexual conduct, did entirely inappropriate gynecological examinations which he claimed were helpful for treating muscular and other problems.

Kline argues convincingly that Sims and Nassar are only two of many “tinkerers,” physicians who crossed the “cross[ed] the boundary between treatment and abuse.” One of the most interesting chapters of her book is previously unreported behavior of Robert Latou Dickinson, another revered historical figure in gynecology. Among Dickinson’s achievements was his advocacy in the early 20th century for gynecologists to ask questions about women’s sexual behavior, and give medical advice, as part of routine clinical care. But Dickinson’s pelvic exams involved actual stimulation of his women patients, purportedly as part of his research but, in retrospect, creepy. Dickinson had a particularly inappropriate decades-long relationship with one of these patients. As a reminder of how complicated many historical figures are, Dickinson may have been the first physician to propose that pelvic examinations routinely include a chaperone — although it’s unclear whether he always did so.

advertisement

The book also delves into another unfortunate chapter in the history of pelvic exams: the examinations of patients under anesthesia that I was offered the chance to perform in medical school. The logic behind them was that it was much easier to examine a woman and learn about pelvic pathology when she was about to have surgery and she could not feel the probing of an inexperienced student. I remember professors saying that these exams would be a boon to our conscious patients, as we would not be learning on them. I joined several students in declining to participate as the women had not been told these “extra” examinations would occur and had thus not given consent.

I returned to the same institution as a faculty member teaching bioethics in the 1990s, and learned that students were still being offered the chance to perform these consent-free exams. When they raised similar concerns, I helped to organize meetings with the gynecology department to try to curtail the practice. As I recall, there were some faculty who continued to defend the exams, but the senior faculty promised to make changes.

The medical literature at the time contained many articles on this topic, with some characterizing the behavior as assault and criminal. But in a good example of how conservative and resistant to change physicians can be, it is only recently that the Department of Health and Human Services has attempted to codify consent procedures.

In the interim, medical schools like mine found a fantastic alternative to having students practice on unconscious women. Pelvic instructors, like the ones I met in the 1980s, first began teaching students in the 1960s. Learning from them remains one of the most vivid memories of medical school for me. The women began by giving explanations of why they thought such teaching was necessary and why they had chosen to do so. When it was time to proceed, they carefully walked us through the examinations as we performed them. Say “please separate your knees” instead of “spread your legs” was just one of the pearls they taught us — and I use it to this day.

advertisement

And finally, the pelvic exam, despite its frequent misuse, has also proven of great value medically. Perhaps the greatest success in cancer screening, the Pap smear, was first performed by pathologist George Papanikolaou in 1925. By gently scraping a carefully exposed cervix, Papanikolaou was able to identify precancerous cells, which could be treated by surgery, thus preventing actual cervical cancer. Despite many delays, by the 1950s the American Cancer Society and other organizations were aggressively promoting annual Pap testing. Mortality from cervical cancer has declined over 50% during the past 50 years.

The pelvic exam, when performed professionally and for appropriate reasons, remains a cornerstone of medical practice. But as “Exposed” reminds us, those performing it should do so with the utmost care, never forgetting how it has been misused.

Barron H. Lerner, professor of medicine and population health at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, is the author of “The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son and the Evolution of Medical Ethics.”