If anyone should have lobbied against the use of vaccines in this country, it was my family.

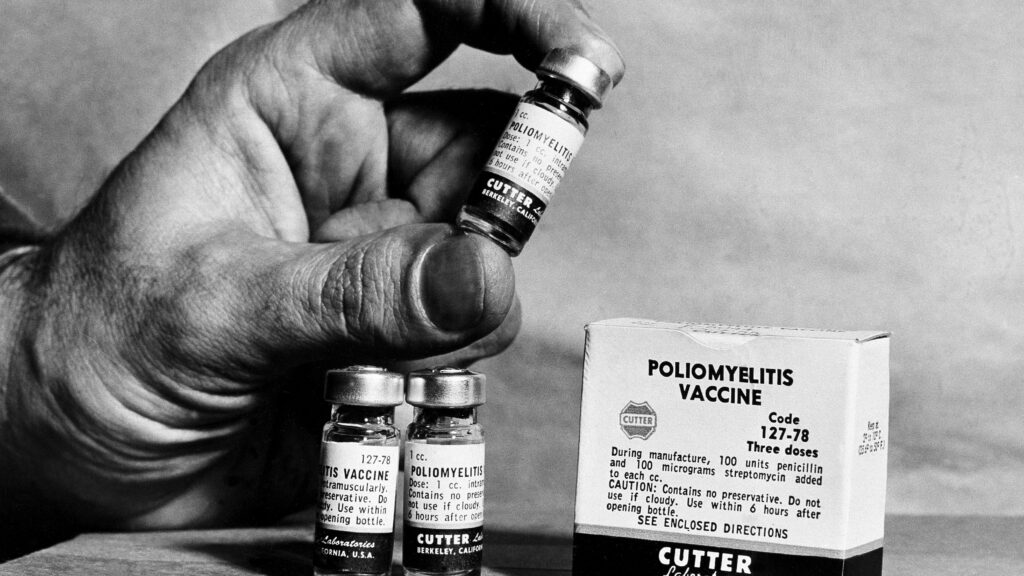

My Aunt Jean, my father’s older sister, was a victim of the infamous Cutter vaccine, an early variant of the polio vaccine presumed to contain an inactivated version of the live virus. Except that it wasn’t inactive. Some 200,000 children in Western and Midwestern states received that vaccine in the spring of 1955. That number included three of my cousins — Aunt Jean’s children. The dosages had been administered by my father, then chief resident at Herrick Memorial Hospital in Berkeley, California. His father, my grandfather, was then the hospital’s chief administrator. The vaccine had been offered to the young members of the families of health care workers, and so my cousins lined up and were inoculated.

advertisement

The rest of that tragic story has been recounted in the aggregate: 40,000 cases of polio, 200 children paralyzed to some degree (one of the vagaries of polio is that it attacks everybody differently), several dozen people killed. My cousins all contracted mild cases but emerged without ongoing health issues. My aunt, however — a vibrant 29-year-old mother of three young boys — caught the virus from them. She spent the following six months in an iron lung and nearly died. Her doctors told her that she might make it to age 30 but had little chance of surviving long with the damage to her lung capacity and swallowing muscles.

Easy story, isn’t it? Vaccines are the problem. Science isn’t perfect and we shouldn’t trust it.

Except that’s not the lesson that my aunt or my father took from this horrible experience, not by a long shot.

advertisement

They had already seen children dying or permanently disabled by the ravages of the virus. Pediatrician Paul Offit, in his study of the Cutter incident, reminds us that before the vaccine arrived, in all its bumpy and imperfect beginnings, tens of thousands of children were maimed or killed by polio every year. Parents fretted over sending their children to swimming pools for lessons, and by the 1950s feared the frequent summer disease outbreaks almost as much as the atomic bomb. We don’t have to wonder what would have happened without the arrival of the vaccine, because so many families lived that reality. We know.

My father knew. I asked him, many years later, what it was like to be the one that distributed that vaccine to his nephews, and then helplessly watch the terrifying illness attack his beloved sister. He answered immediately: “I have no regrets. That vaccine was flawed, but polio was horrible, and there was no other humane choice. Science isn’t perfect, but it is the best human beings can do to provide protection.”

I have hesitated to write this story for many years, ever since vaccines themselves became the object of suspicion and fear. Won’t this story simply give fuel to anti-vaxxers, so ready to latch onto a tale of vaccines gone wrong?

But that is exactly why this story needs to be told. It is a tale of personal tragedy, yes, but also of a faith in public health, in the greater good, and in the ability of science to self-correct as it pushes toward cures for horrible diseases. Those who have died from polio can’t tell that tale. We are left, then, with stories from critics, most of whom do not have evidence to back their claims of scientific failure. And they are too often led by those looking to benefit from unregulated “cures” with even less of an evidentiary basis.

My aunt was the victim of regulatory failure. Yet she saw the greater good that was at stake and chose to remain focused on that. She lived to age 70, disabled but enjoying the presence of her children and grandchildren, building a rewarding career as a counselor, and knowing that her life, while forever altered by polio, was not defined by it. My father and grandfather also kept their eyes on the possibility for self-correction in health care. Other vaccine companies, following Jonas Salk’s protocol, produced viable vaccines that saved a generation of children, including me, from having to fear swimming pools or public skating rinks. We lined up for our sugar cube vaccines at school to contribute to the public good that would, we knew, save many more individuals from the ravages of the virus.

advertisement

I don’t share Jean’s story to suggest that disease has redeeming possibilities for those who survive. Perhaps it can, but when we have the means of prevention in front of us, we should celebrate and seize that victory, however imperfect. It is a shoutout from the front lines to celebrate the breakthroughs of research, recognizing that not everything will be an unqualified win. Public health requires us to think beyond individual needs, to recognize that unless vaccines are widely distributed (and yes, even required in some cases) they will be of no use to anyone. It also urges us to recognize that some battles have already been litigated and do not need to be revisited when the evidence of success is overwhelming.

The recent back-and-forth between Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and President Trump regarding the polio vaccine reflects a lack of logic in both respects. In responding to Kennedy’s vaccine criticism, Trump recently remarked that he would want to end some childhood vaccines “if I think it’s dangerous.” But dangerous for whom? For the one, the 200, or the millions who might benefit? I hate to contemplate harm to anyone, but as my aunt would have attested, there are lesser and greater risks in life. All that science can do is mitigate risks, not eradicate them.

Similarly, clear success of vaccine use, demonstrated by years of health statistics in the case of polio, gives lie to the notion that we should relitigate all decisions regarding vaccination, as Kennedy and others might have it. This is not to say that we should eliminate robust regulatory mechanisms that detect potential problems and question methods. But it does raise the obvious question of what sort of proof is being sought. What qualifies as adequate scientific evidence of failure or success? I have not heard any vaccine critics answer that question clearly and precisely. Until they can and do, we are left with little more than fearmongering without a clear goal in mind.

My aunt would have had no patience for these debates. Perhaps because of her close and prolonged brush with death, she always kept the bigger picture in mind. She vaccinated her family on recommended schedules. In her later years she developed post-polio syndrome, a pernicious condition that gradually robbed her of the gains her health had made since the 1950s. Still, she kept her eyes on the present and future, never turning her anger on the faulty vaccine that had altered her life. Millions of children lived long and healthy lives because of the polio vaccine, and public memory of the horrible history of a previously uncontrollable virus faded from view for many. Science is what removed that scourge, and despite its imperfections, she knew it was an ally to be nurtured and even questioned with precise evidence, but never dismissed without cause.

advertisement

Laurie Maffly-Kipp is the Richard Lyman Bushman Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia.