Every time I have moved house — too many times — the cardboard box has followed me, a reminder of my unfulfilled promise to Jon Miller. It contained his journals and letters, mostly from the last 18 months before his death from AIDS/HIV complications in 1990.

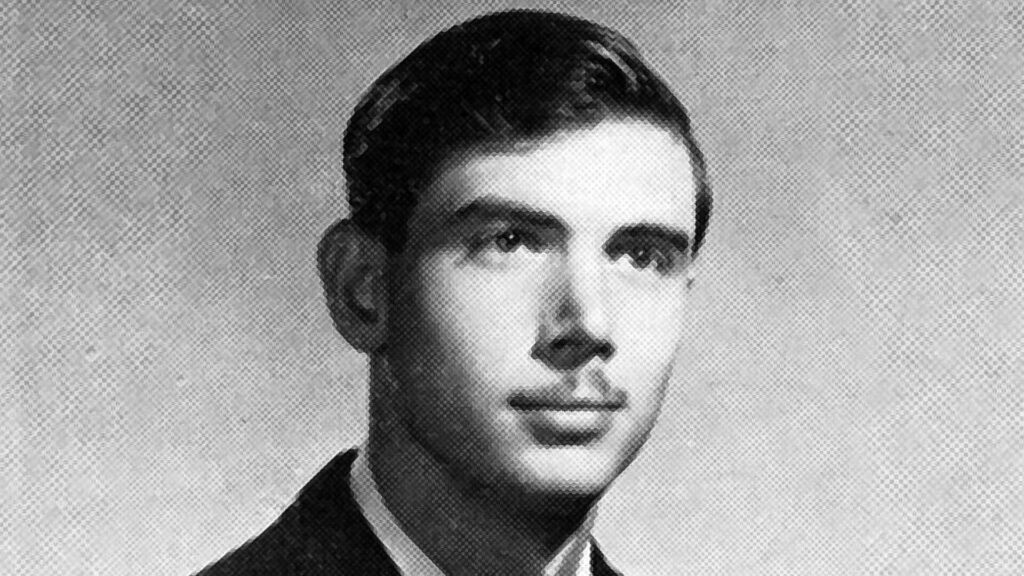

Jon Miller was my first city editor. I was 19, an Antioch College student on a co-op job as a reporter for the Troy, Ohio, “Daily News.” It was the bitter winter of 1968, the winter of the Tet Offensive. I look back at that time and marvel at how self-absorbed I was. Jon seemed so much older — 26, a chain smoker and hard-nosed newsman who had to put up with my inexperience. But he took an interest in my writing because I had a knack for jazzing up simple assignments — weather forecasts, the hog market report, and the little controversies that roiled the rural school boards I covered. He was a wonderful writer and editor with a style that journalism no longer values — creative, playful, and readable.

advertisement

Soon after I went back to my college near Dayton, Jon left Troy for a “big city” Dayton daily. I would run into him occasionally, but I also began to get hints from newspaper friends that Jon had what was then considered a dark secret. About the time I got married, Jon announced he was moving to San Francisco. Now there was no secret.

My wife and I ended up in Los Angeles. On a weekend trip to San Francisco, Mary and I looked him up in the Castro, where he was leading a wide-open life in the 1970s gay scene. But he was still Jon — tall, dark, and funny. Eventually Jon moved down to Los Angeles to edit an airline magazine. After Mary and I left L.A. for sunny Ohio, we lost touch, although journalist friends reported sightings.

In 1989, I got a letter from Jon. He had been diagnosed with AIDS/HIV. I responded by saying how sorry I was to hear the news. He accepted that. Then he asked a favor. After the initial shock of the diagnosis, Jon had started to keep a journal. Would I look at it?

advertisement

And so Jon’s cardboard box arrived with its pile of dot-matrix printed manuscripts bundled inside. Mary and I took it to the dining room table and read it in relays, passing sections back and forth as we finished each. We were shocked and saddened but also amazed by Jon’s unblinking eye for the absurd. The journal, which began as therapy, gradually became a chronicle of his AIDS plague year. There was the humiliating cascade of symptoms from oral thrush to Kaposi’s sarcoma, but there were also Jon’s sardonic stories about his visiting nurse, who kept him going with the relentless cheerfulness of a combat zone medic. With her AIDS caseload, I guess that’s what she was.

Jon asked me to read, edit, and possibly find a publisher for the journal. He didn’t have the energy for that anymore. As he grew sicker, I wrote letters, made calls, forwarded chapters, and got nowhere. Jon Miller died in May 1990. He was 49.

His journals moved with us through all our houses since, a cardboard reproach in a drawer. This summer, guilt finally moved me to search for an AIDS archive, if there was such a thing. I had tried before without luck, but this time I succeeded: I found Polina Ilieva. Polina is the archivist who oversees the AIDS History Project at the University of California, San Francisco Library.

I emailed Polina late one night. She responded early next morning. UCSF’s HIV/AIDS archive would be “honored” to have Jon’s journals, she said. I was relieved. I’d feared that the papers of a little-known journalist wouldn’t be serious enough for a medical archive. Quite the contrary, Polina said. The archive had only one personal journal like Jon’s, and while the archive collects oral histories, contemporary accounts of the early AIDS years are exactly what she is looking for.

The generation of physicians and scientists who first battled AIDS are retiring or dying, Polina explained, and their official papers are flowing into UCSF. But, she told me in an email, “we still have so many gaps and silences in the HIV/AIDS archives. Just like medical history in general, which primarily represents the medical establishment and researchers, the voices and experiences of PWA (people with AIDS) have been largely missing. In Jon’s collection, we will make another small step in remediating this imbalance.”

advertisement

But why are personal accounts so rare? Surely there were thousands of people with AIDS keeping journals, writing letters, or recording diaries. What became of that material? Polina has theories but no conclusions. She believes that in the early years of the epidemic, the families — suffering from some combination of grief, shame, and confusion — of those who died simply didn’t know what to do. Much was simply lost. Some was deliberately destroyed. But somewhere there are surely more cardboard boxes like Jon Miller’s.

This is a plea for living memory, or at least for memory that lives on in half-forgotten boxes. The HIV/AIDS epidemic is far from over. In 2024, UNAIDS estimated that since the beginning of the epidemic, 88 million people have been infected worldwide and 42.3 million have died from AIDS-related causes.

AIDS/HIV was neither America’s first epidemic, nor our last. There are still vital lessons to be learned from the early AIDS years when panic and hypocrisy in the U.S. drove public reaction, forcing the gay community to truly come out and fight for its life. But we must never forget that public health is always personal and that memory is a fragile resource.

Good causes usually plead for money. Financial donations would be welcome: The AIDS History Project is certainly not overfunded. But this is a special plea, a call to family, friends, and other survivors of the first HIV/AIDS onslaught to ask quiet questions and poke around in dusty corners. You may have a cardboard box of your own.

John Fleischman was the longtime senior science writer for the American Society for Cell Biology. He is also the author of a nonfiction bestseller for middle-school kids, “Phineas Gage: A Gruesome but True Story About Brain Science.”