Outside the main entrance of World Health Organization’s headquarters in Geneva stands a bronze statue of an African boy walking ahead of his blinded father, guiding him with a long stick they both hold.

This poignant artwork depicts how onchocerciasis, an ancient disease commonly known as river blindness, impacts many of the world’s poorest people. Several replicas have been installed around the world, including the Carter Center in Atlanta.

advertisement

The statue conveys many things: service, hope, the pride possessed by people who many consider vulnerable. Above all, it underscores how access to health enables each of us to live with dignity, no matter income or birthplace.

President Jimmy Carter, whom I was privileged to have worked with closely for two decades, embodied and championed all this, and more. While attending services in Washington celebrating President Carter’s life, I will pay tribute to the lasting legacies he left: the partnerships and programs that protect millions from the global threats of disease and war.

President Carter saw afflictions like river blindness, malaria, and Guinea-worm disease as debilitating drivers, and results, of poverty and insecurity. In the 1980s, around 3.5 million people in Africa and Asia lived with Guinea-worm disease, a debilitating condition with no vaccine or treatment. It is caused by drinking stagnant water infected by parasites that, once ingested, grow into long worms that burrow, painfully, out of the patient’s body through their skin.

advertisement

President Carter understood this disease preyed on the world’s poorest but could be fought with strategies owned by affected communities and countries, and implemented with simple tools: in this case, a filter to separate the parasites from collected drinking water at source.

In 1986, the World Health Assembly called for the disease’s eradication. As the years went on, the Carter Center, which the president founded with his late wife, Rosalynn, and Emory University would play a leading role in tackling this challenge. It supported heads of state and health departments in affected countries, and collaborated with global partners like WHO, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Gates Foundation to mobilize needed resources.

Since 2000, the disease has been eliminated from Southeast Asia, and in Africa, it is very rare — about a dozen reported cases in 2023. Global eradication is in sight, a result that ranks as one of President Carter’s most important post-presidential achievements.

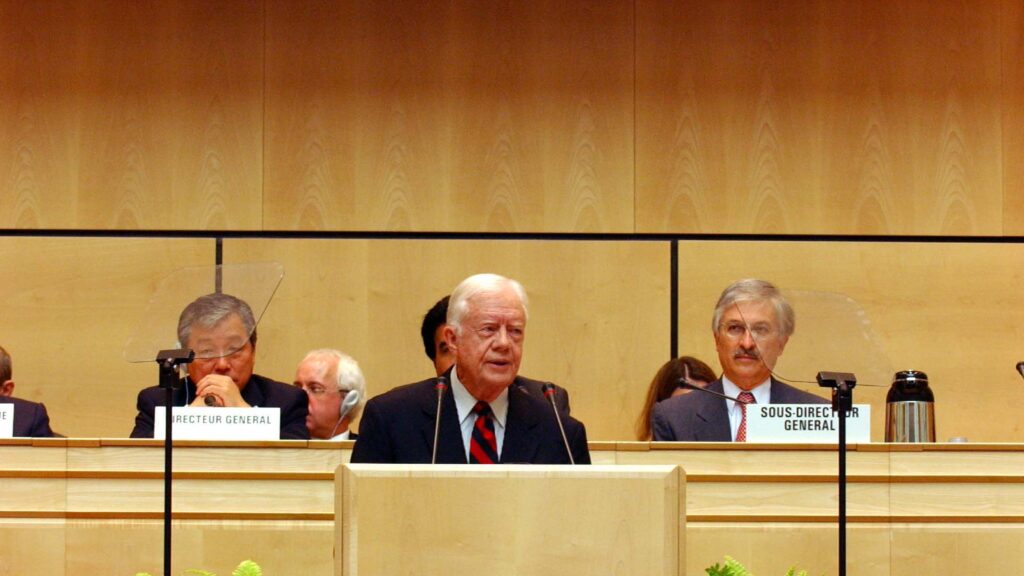

I first met President Carter while I was serving as minister of health in Ethiopia. He visited the country to inspect the health projects his center was supporting. What impressed me then, and again in the many times we met after, was his humility and commitment to service. He strategically leveraged his position as a former president of the United States to open doors to governments around the world and help build country-led solutions.

That meeting in Addis Ababa, some 20 years ago, was immensely important personally. It started a close relationship, built on shared goals of achieving health for all, respecting individual dignity and human rights, and pursuing peace. I was humbled in 2011 to be the first non-American recipient of the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award. I also appreciated the president’s support of my campaign to become the first African elected director-general of WHO.

The impact the Carters have had on people’s well-being extends to mental health. Their center has drafted policy, reduced stigma, and raised the importance around mental health in the U.S. and beyond. In 2023 Rosalynn Carter was presented with the WHO Award for Global Health to recognize her lifetime achievement in working on mental health issues.

advertisement

Importantly, President Carter recognized the links between health and peace. The Carter Center, he once said, “always considered peace and health to be interrelated. The right of people to live in peace and the right of people to have adequate health care, and to have their children survive, are inseparable basic rights of a human being.”

By bringing Egypt and Israel together to forge the historic Camp David Accords, and their 1979 peace deal, he showed it is possible to end war and build secure futures for people tired of conflict. The need for this in the Middle East today has never been stronger.

In 1995 during Sudan’s civil war, President Carter astutely negotiated a six-month ceasefire to give health workers the space and security to undertake programed related to Guinea-worm disease, river blindness, and other health challenges.

During and after his presidency, President Carter also demonstrated the political and moral leadership of the United States over and again, and its role in advancing global security, collaboration, and health to protect everyone, in America and around the world.

These examples, and more, presaged today’s volatile world.

The divide between rich and poor has never been wider, nor has wealth been so concentrated in the hands of so few. And the perils we collectively face — wars, outbreaks, and climate change — have never felt more pressing. But President Carter’s example, as a leader, a humanitarian, and a human, can guide us through these unclear times. I urge us all to follow his lead.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is director-general of the World Health Organization.