The therapy, an infusion of CAR-T cells designed to kill the lymphoma, was going well. Nearly a month after the treatment, the engineered cells had crushed the cancer, and the patient, a 49-year-old woman in the Netherlands, appeared to be cancer-free. But two weeks later, something was wrong. The patient couldn’t remember having been in the hospital or, indeed, ever being treated for lymphoma. When she returned to the hospital, a scan showed parts of her brain were swelling.

The patient had experienced a rare complication stemming from a common herpes virus infection, HHV-6. While researchers are still puzzling out the cause of the complication, new research suggests that a key CAR-T manufacturing step can reactivate HHV-6 in T cells. The work, published in Nature on Wednesday, showed that this reactivated HHV-6 is present in some approved CAR-T products.

advertisement

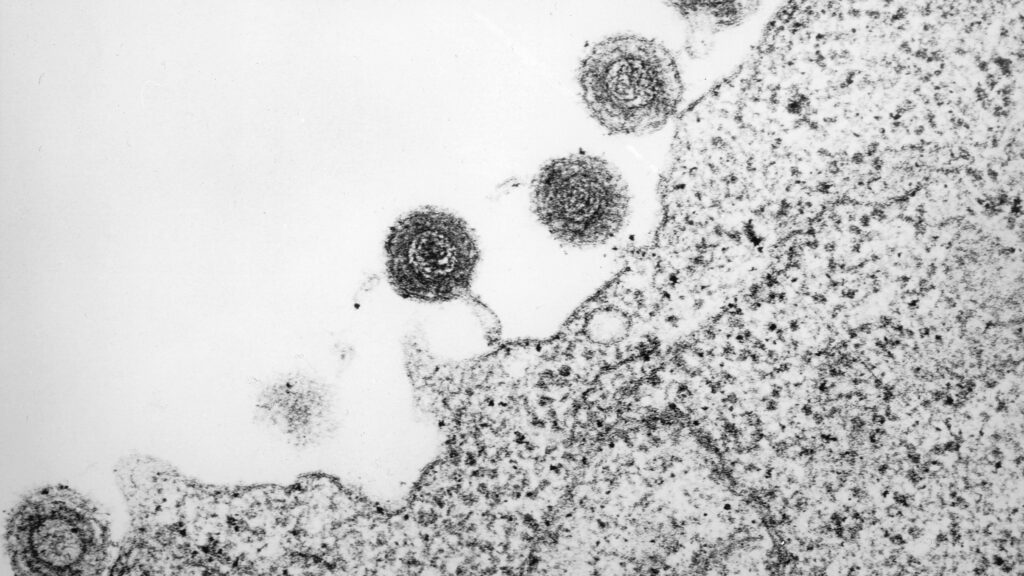

Most of the time, HHV-6 is an unobtrusive passenger. The virus snatches a ride in nearly every human on the planet, and takes a seat in T cells, where it can stay silent for decades. But when T cells are taken out of the body and cultured in a lab, a step in creating every cell therapy product like CAR-T, HHV-6 can surge up from its slumber and begin replicating, said Caleb Lareau, a cancer immunologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and lead author on the study. The infusion of the now active HHV-6 might contribute to a dangerous infection in an already weakened cancer patient.

These complications can be dangerous. The patient, whose case was reported in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, suffered long-term memory impairment from the viral brain inflammation, encephalitis. Still, Lareau emphasized that fear of these complications should not deter patients from accepting the therapy, especially since the complication can be successfully treated. CAR-T has offered many patients not only a last chance at a cure but good odds of one.

“These are transformative therapies, and we should not pump the brakes on them,” Lareau said. “But there is a gap where patients are dying, and we don’t know why. This might provide insight into one facet into why patients might develop complications.”

advertisement

This particular complication has been poorly understood, Lareau added, but more research and awareness on how it occurs and what contributes to it — like CAR-T manufacturing steps — might help save lives and make CAR-T safer. STAT spoke with Lareau about this work. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How often does this complication occur?

You see anecdotes in the CAR-T literature of HHV-6 encephalopathy. It hasn’t been investigated systematically, and it’s not something being talked about very often. So, very basic questions about how often does this occur and is it likely to happen in some populations versus others — we’re in the very early days of understanding this. But the belief is that it’s quite rare. The New England Journal paper outlined eight documented cases of HHV-6 encephalitis, and it drew attention to the idea that there might be something about this therapy and this virus that we should be paying more attention to.

By and long, if you have a cancer where CAR-T is approved, your best bet is to get these therapies. The outcomes are transformative. This complication is treatable. If I had leukemia or lymphoma, I would want CAR-T therapies.

What made you want to study this?

We had some evidence in the lab already about HHV-6 possibly becoming reactivated in T cells, so it was having some preliminary molecular evidence and then these case reports in the New England Journal that really made us pursue the topic more hotly. There was one specific trial where a 4-year-old girl was treated with CAR-T, and she had refractory acute leukemia. Her cancer was basically in full remission as a function of the therapy, but she ultimately passed away four weeks after receiving the CAR-T.

So, the CAR-T was working great, but her cause of death was actually attributed to HHV-6 encephalitis. So that was one of these motivating anecdotes where there have been patients that were ostensibly doing very well on CARs, but this viral complication was ultimately lethal.

How did you do the study and what did you find?

It was entirely a data-driven project. We looked in everyone else’s data and looked to see if they have virus. When you do this for herpes, you see a couple of experiments out of San Diego and another out of Germany eight years ago where they cultured T cells and did RNA sequencing to see what changes. One in 3 or 1 in 4 cultures in those sets led to massive amounts of HHV-6 reactivation. That was kind of the go, no-go experiment.

Then we showed through single cell sequencing, a reanalysis of published data, CAR-T cells that were positive for HHV-6 taken from blood draws of people receiving CAR-T therapy. I remember the day I got this result. We’d been waiting for this data from a big paper that required controlled access, and it was the home run.

As a researcher spending years on a project, you feel exhilarated. Like we know more today than yesterday. But, given the direct relevance to patient’s lives, I felt a burden to get the story right. The conclusion from this paper should not be to stop giving CAR-T therapy. For some patients, this will be very relevant, but by and large it’s still a rare complication. I’m glad that we’ve identified this mechanism, because hopefully it will save lives in the future.

If HHV-6 can just lay dormant forever, why is it getting reactivated during CAR-T creation?

We don’t know why the reactivation occurs. It’s probably a somewhat stochastic process where when you have a latent infection, viruses will be periodically poking their heads out and saying, “Is this a place where I can replicate?” If you’re in the body, the answer is typically no. The whole immune system is there to respond to the virus. But then you’re taking the cells out of their natural context with a competent immune system to keep this in balance, and putting the cells in a culture which is idealized for cell proliferation. This is conjecture but it may also be ideal for the virus to spread.

Something we think that matters is the duration of the culture. We have this donor where we don’t see any HHV-6 after the standard manufacturing window. Then, we took the product and cultured it longer, and then we saw the virus.

How much of the viral encephalitis is because HHV-6 is getting activated when you’re making the CAR-T versus the patient just being in an immunocompromised state due to cancer and chemotherapy?

It’s difficult to say what exactly led to the clinical presentation of viral encephalitis. What we do know is the process of engineering cells can lead to higher viral levels, and we detect them in vivo through genomic approaches. We are having more virus delivered systematically, and it’s unclear if that’s causing the encephalitis.

If you were to ask the biggest critics of this work, you can see HHV-6 encephalitis without CAR-T. There’s a lot going on with cancer patients. My counter to that is that things are happening to these cells in the lab that we don’t fully understand, and this is almost certainly contributing to some of these complications. Our ability to suss this out is step one of understanding fully what this looks like.

What do you want patients and clinicians to take away from this?

In my mind, it’s something I want to communicate to clinicians. For some patients, it may matter, but for most, CAR-T will more likely than not give you a great outcome. There’s growing awareness of this for clinicians that when there is certain atypical neurotoxicity in patients, HHV-6 is something they screen for more readily. It is treatable.

The overarching theme is that this can happen. The hope now is that given the degree of characterization we provide in the paper, it’s something the community can be aware of, and lives can be saved as a function of further understanding this phenomenon.