It took Richard Huckabee nine years to get a Parkinson’s diagnosis.

A district manager for a convenience store chain, he first noticed symptoms in 2004 when his voice would suddenly falter while speaking to large groups of employees. “It’s probably just stress,” Huckabee remembered his doctor saying. A year later came the brain fuzziness, with Huckabee forgetting his colleagues’ names, having his thoughts freeze mid-conversation, and fully losing his ability to multitask. At this point, his doctor convinced him he had Lyme disease and put him on steroids. “It was awful. For six months, they said, ‘Just keep trying,’” Huckabee recounted.

advertisement

Before the symptoms started when he was 44, Huckabee was in the prime of his career, having received a promotion and taken over a new territory in northern Virginia. “What managers took 80 hours to do, I would do in 35 hours,” he said proudly. But in 2011, the company terminated Huckabee because he was no longer able to do his job. “I couldn’t argue with them because I knew I had issues,” Huckabee continued. No doctor, however, could tell him why.

Huckabee’s story is unfortunately all too common. In 2019, 40% of Medicare beneficiaries living with Parkinson’s, or nearly 250,000 Americans, didn’t see a neurologist for their disease, according to a new study that is the largest contemporary analysis of health care utilization among Parkinson’s patients. This study, published Monday in npj Parkinson’s Disease, also found that 80%-90% of these Medicare patients didn’t meet with a physical, occupational, or speech-language therapist and that over 95% with depression or anxiety didn’t see a mental health professional.

Across nearly all metrics, these gaps in care were worse for Asian, Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans, as well as women and rural Americans. For instance, around 5% of Black, Hispanic, and Native American patients — and 7.8% of Asian patients — saw a movement disorders neurologist, compared to about 10% of white patients.

advertisement

The study, funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation and Parkinson’s Foundation, drives home the extent to which many Parkinson’s patients struggle to access care for their physical and mental health. With about a million Americans living with Parkinson’s and nearly 90,000 new cases being diagnosed each year, the study highlights the need for improving care coordination between primary care providers and specialists, expanding training for general neurologists, and improving access to care for communities of color.

What’s driving the gaps in care?

There are multiple reasons to explain these disparities, with Parkinson’s patients lost at every step of the way, according to a half-dozen geriatricians, neurologists, patient advocates, and mental health professionals interviewed by STAT.

The challenge begins with identification of the illness, because there is no diagnostic test for Parkinson’s or even a standard presentation of disease. “It’s got motor, cognitive, psychiatric, and other physical symptoms. It’s not just one disease,” said Laura Marsh, a professor of neurology and psychiatry at Baylor College of Medicine, “and then each of those motor, cognitive, psychiatric aspects progress in different ways.”

A Black man, Huckabee said his diagnosis was further complicated because his symptoms were repeatedly dismissed and ignored by his physicians, perhaps because 85% to 90% of Parkinson’s patients are white. “We don’t fit the profile,” Huckabee said. “Some of the doctors said I’m taking it too serious,” he added. “Some of them said, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’”

According to Vanderbilt University professor of geriatric medicine and senior vice president for health equity Consuelo Wilkins, stories like Huckabee’s are far too common, especially with significant biases in who gets specialty referrals — and, by extension, access to a diagnosis and higher levels of care.

Even a referral is often not enough for some Parkinson’s patients because there simply aren’t enough neurologists. James Beck, chief scientific officer of the Parkinson’s Foundation and senior author of the new study, estimated that, across the U.S., there are 3,000 to 4,000 neurologists that see Parkinson’s patients and only 660 movement-disorders neurologists, who are specially trained to care for these patients.

On average, that translates to roughly 1 subspecialist per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries with Parkinson’s. But these subspecialists are also not spread out uniformly across the country, with only six practicing in rural areas. Physician shortages might help explain why 30% of patients with Parkinson’s had their care managed by a primary care provider and 10% didn’t see any physician at all in 2019.

Beyond months-long waiting lists and difficulties scheduling appointments, some patients simply can’t make it or don’t feel comfortable going to their appointments. Indeed, Wilkins noted that neurologists and movement-disorder specialists are predominantly located in suburban white neighborhoods, making it more difficult for communities of color to access their services. “If English is not your preferred or primary language, then who’s there and available to provide that care — culturally and linguistically appropriate?” Wilkins asked. “The disparities and inequities just start to compound.”

The study’s mental health findings are also particularly disappointing, according to Roseanne Dobkin, a clinical psychologist and professor of psychiatry at Rutgers University. In the study, 53% of Parkinson’s patients had a diagnosis of depression or anxiety, but less than 2% had a clinical psychologist visit — and less than 4% a psychiatry visit.

Mental health stigma may help explain why these rates are so low, with patients afraid to talk about their symptoms or see a specialist, according to Marsh, the professor at Baylor. So, she thinks part of the solution might be to broaden the disease narrative.

“Parkinson’s is not just a movement disorder,” Dobkin similarly emphasized. “Depression and anxiety are symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. They’re not a reflection of personal failure, or weakness, or inadequacy.” In fact, Marsh said that many of her patients have anxiety or mood disorders even before they find out they have Parkinson’s.

The stakes are high for getting these patients access to mental health care, with depression cascading into faster rates of physical and cognitive decline, higher rates of caregiver distress, and increased rates of health care utilization and costs, Dobkin said. “We all need to spend more time focusing on and talking about the neuropsychiatric aspects of the disease process, just like specialists spend tremendous time talking about the motor aspects.”

Need for fundamental changes

Sharon Brangman, chief of geriatrics at SUNY Upstate Medical University, said she recognizes the value of quantifying these gaps in Parkinson’s care. “But I’m not sure how many more needs assessments we need,” Brangman said. “What’s needed are fundamental changes, and that’s where the hard work comes.”

Maria Moro-de-Casillas, a movement disorders neurologist at Hartford HealthCare, knows this intimately well. After noticing for years that Hispanic patients were underrepresented and receiving lower-quality care in the hospital’s Parkinson’s clinic, she opened the Spanish-Language Movement Disorder Clinic in 2020 to tackle three key barriers: transportation, language, and culture. For one, the clinic was deliberately set up in downtown Hartford to be more central and accessible by public transport. Secondly, there are no translators in this clinic. “All the people who work with me are either Hispanic themselves or well-versed in Hispanic culture,” said Moro-de-Casillas.

That cultural sensitivity is the critical third component because “the type of care that you provide in your regular suburban clinic,” she said, “is not going to work in a minority clinic.” For example, recognizing the fundamental unit of family in Hispanic culture, she invites patients’ children and grandchildren to the appointments. And understanding how difficult it is to openly talk about mental health, she proactively explains to patients that depression and anxiety are normal symptoms and nothing to be ashamed about.

“I think the Lord sent her to me,” said 73-year-old Luis Muniz, who confessed to Moro-de-Casillas that he was feeling depressed after his wife died. “She’s dealing with my movements, but she is so helpful and kind. She deals with my other problems as well,” from cholesterol levels to sleep quality to memory loss.

Other groups have taken a similar approach to providing culturally competent Parkinson’s care, from Tufts University researchers running a clinical trial on creating more inclusive programs for Asian Americans to University of Arizona clinicians hosting neurology clinics at Indian Health Service and tribal health care facilities on the Navajo and Hopi reservations.

The Veterans Health Administration may offer another template for addressing treatment gaps for Parkinson’s patients, despite shortages in specialists. In the VA, a nurse follows up with patients to track mental health symptoms over time, and if they don’t improve, the primary care doctor consults a psychiatrist, according to Marsh, who is also the executive director of the Mental Health Care Line at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center. With psychiatrists focused on seeing patients with the most severe conditions that might not be responding to treatment and supporting primary care physicians otherwise, a small group of mental health professionals can care for a much larger group of patients.

The VA has a similar system for neurology care as well, featuring a hub-and-spoke model with six specialized Parkinson’s centers across the country and dozens of regional specialty clinics to provide care closer to home. In coordinating care and sharing expertise, a limited number of movement disorders specialists can thus care for a greater patient population.

‘Felt like a cruel joke’

When Huckabee was finally diagnosed with Parkinson’s by a neurologist, he was both elated and crushed. “I was happy to find out what I finally had,” said Huckabee. “I was devastated at nine years of in-and-out doctors, and here is this one doctor that says in 10 minutes, ‘You have Parkinson’s disease.’” It felt like a cruel joke.

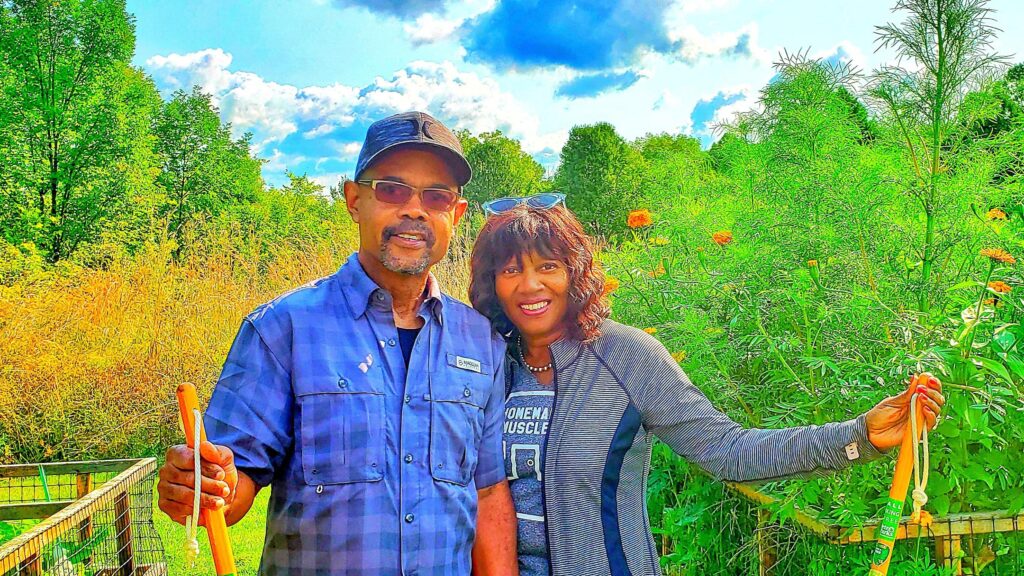

Now at the Cleveland Clinic, Huckabee has a whole team managing his care, from a movement disorders neurologist who enrolled him in new research trials to an occupational therapist who helped him learn how to drive again. A few years ago, Huckabee even started seeing a therapist after a drug he was prescribed led to a gambling addiction. “It got so bad that my wife was almost ready to leave me,” Huckabee said. But his therapist was able to rehabilitate that relationship and, in consultation with his neurologist, get him off that medication.

Huckabee recognizes that he just happened to be lucky — lucky to live near a world-class academic medical center, lucky to have a Medicare plan that covers all his Parkinson’s care, and lucky to finally be diagnosed. “We need more specialized places so that people of color could feel more comfortable, could feel like the doctors really care,” said Huckabee.